Legal Protections for State Pension and Retiree Health Benefits

Findings from a 50-state survey of retirement plans

Overview

The nation’s public retirement systems have emerged from a decade of unprecedented changes to benefit design and financing, yet many jurisdictions are still short of what they need to fully fund retirement benefit obligations.

Since 2000, when public retirement systems were almost fully funded, states have seen aggregate unfunded pension liabilities grow to more than $1 trillion, with an additional $700 billion in unfunded retiree health benefit costs. As the gap has widened, retirement system contributions from taxpayers have doubled as a share of state revenue, but they have still fallen short of what is needed to improve the overall funding situation.

While past reforms will lower costs somewhat over the long term, pension funding will continue to be a financial pressure in many states as large numbers of older employees retire and revenue growth is relatively weak. In addition, continuing market volatility, along with the threat of another downturn, could increase pension funding costs and pressure policymakers to consider additional reforms at a time when they also need to continue funding core government services such as schools, public safety, and infrastructure.

With that backdrop, it is important for policymakers to understand the legal protections afforded to workers’ retirement benefits—and lawmakers’ ability to modify the terms and conditions of those benefits.

The Pew Charitable Trusts conducted a comprehensive 50-state review of state constitutions, statutes, and case law to determine the level of legal protection for not only public employee pensions—a monetary annuity paid throughout the lives of retired employees and often to a surviving spouse as well—but also retirement health care plans. Pew’s research examined the annuity and health care benefits separately because the law in most states treats the two differently. The research also focused on the legal rights of current employees and retirees because retirement benefits can be modified for new employees prior to their date of hire.

This issue brief will explore the highlights of the research, which revealed that state laws vary significantly with respect to:

- The source of protection for employee retirement benefits.

- The aspects or features of pension benefits that are protected.

- The participants who are entitled to such protection.

One reason for the wide variance in legal protections for employee retirement benefits is that state, not federal, law primarily governs retirement benefits for state workers. And in each state, these protections vary by source, be it the state constitution, statutes, or court decisions. Retirement benefits protected by a state constitution can be changed only by a constitutional amendment. A statute, on the other hand, can be changed by the legislature through the standard lawmaking process, or by a subsequent constitutional amendment. And a judicial decision can be changed by a higher court overruling a lower court’s decision; by a court modifying or clarifying a prior decision; or—rarely—by a court establishing a new precedent.

Understanding how retirement benefits are protected is crucial for policymakers as they explore options to manage their state’s increasing pension costs. These options include increasing pension funding, changing plan investment strategies, and reforming design and benefit levels.

Sources of legal protections for pensions

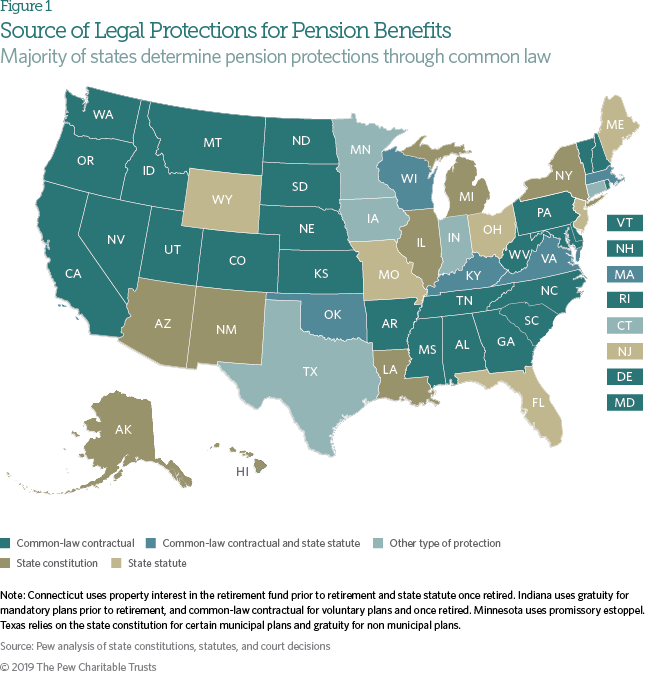

All 50 states protect public pensions to some degree. Pew found that eight states rely exclusively on the state constitution; six states rely solely on statutes enacted by the legislature; and 26 states rely exclusively on court rulings that find pensions to be part of a contract between the employer and the employee—also known as the “common-law contractual approach.” Five states use a combination of judicial decisions and state statutes to protect retirement benefits for public employees, and one state relies solely on judicial decisions. Four states protect pensions in different ways.

Constitutional Protections

Arizona adopts new amendment permitting the legislature to change pension benefits

Arizona is one of only eight states whose constitution prevents lawmakers from adversely altering pension benefits for public employees. However, Arizona is unique in that it is the only state to have passed a constitutional amendment relaxing those protections.

In 2015, Arizona’s pension plans for public safety workers had a funded level of 48 percent, with high costs that imposed an increasing fiscal burden on many local governments. The growing unaffordability was due in part to a provision in the plan mandating permanent benefit increases to eligible retirees in years with excess market returns. The increases were not tied to any cost-of-living index and, once granted, could not be reduced.

Because Arizona’s constitution includes very strong legal protections for public pensions—which are protected as of the first day of employment and cannot be changed to an employee’s detriment for any reason—the courts had struck down several earlier attempts at modifying this provision.

Concerned about the solvency of the pension fund, labor leaders for Arizona’s public safety workers approached state legislators in 2015 with a plan to address the problem. After a year-long collaboration among multiple stakeholders, lawmakers launched a bipartisan initiative to reform the public safety employee retirement plans. These reforms were contingent upon the passage of a constitutional amendment that would allow several specific modifications to the pension system, including changes to cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs).1 In 2016, voters approved the amendment by a margin of 70 percent to 30 percent.

As a result, Arizona replaced the permanent COLA for police and firefighters with a COLA that was capped at 2 percent per year. The reform is expected to reduce the pension costs of new government employees by 20 percent to 43 percent—an estimated taxpayer savings of $1.5 billion over the next 30 years.2

What is protected?

Even among states with the same source of legal protection for pension benefits, the aspects or features protected can vary significantly. The research examined three major categories of pension features to determine the extent of state-level protection: accrued benefits, the rate of future accrual, and cost-of-living adjustments.

Accrued benefits

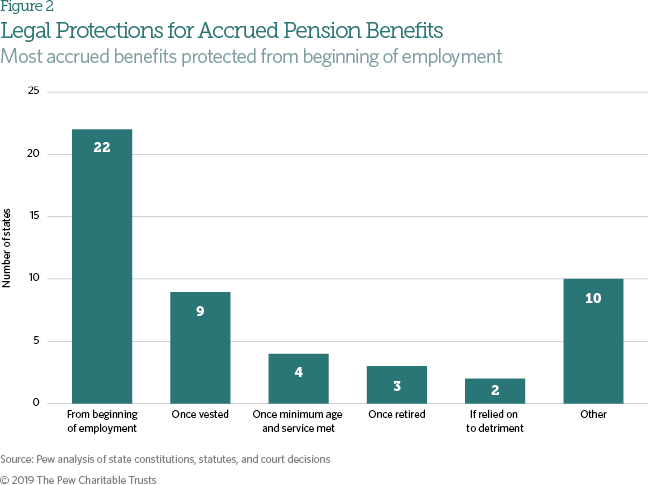

For most public employees, accrued pension benefits are protected against change either from their very first day of employment or once they’ve satisfied the plan’s minimum service requirement. Every state protects benefits that have been earned by working for the employer—called accrued benefits—in at least some circumstances. However, the extent of that protection varies significantly.

The most common approach, used by 22 states, is to protect accrued benefits for all employees from the moment they begin participating in the plan. An additional nine states protect accrued benefits only after an employee has satisfied the plan’s minimum service requirement, commonly referred to as vesting. Four states require both age and service requirements to be satisfied before protection applies, and Iowa, Ohio, and Virginia protect accrued benefits only once a participant has retired. In Minnesota3 and West Virginia,4 accrued benefits are protected only if a participant can show that he or she relied on promised benefits to his or her detriment—for example, by making employment or retirement planning decisions on the basis of the promised benefits. Wyoming protects an employee’s accrued benefits only in the event of plan termination—and, even then, only to the extent that the state has funded such benefits.

The rate of future accrual

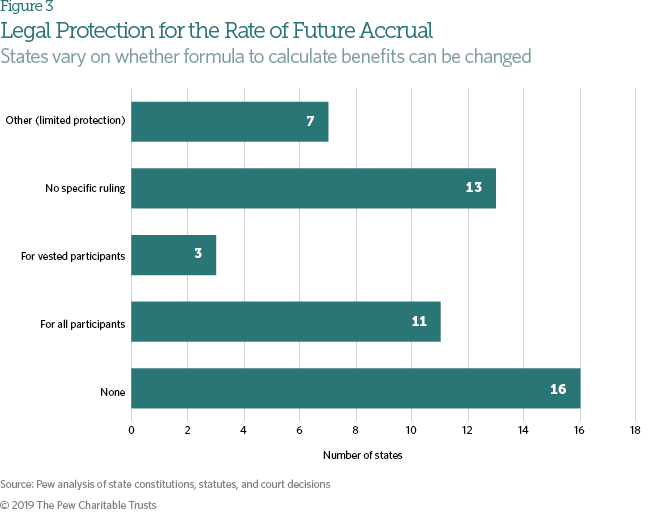

While accrued benefits are generally well protected, the same is not always true for pension benefits that current employees might earn for future service. Eleven states protect all participants against changes from their first day of employment. (In other words, the pension formula can never be less generous than it was on the employee’s first day of work.) An additional three states provide such protection once a participant has satisfied the plan’s minimum service requirements and is therefore vested. Seven states protect the rate of future accrual only for some participants or only in specific situations, and in 16 states there is no legal protection for the rate of future pension accruals. Finally, in 13 states there is no relevant legal authority on the issue of future accruals.

Cost-of-living adjustments

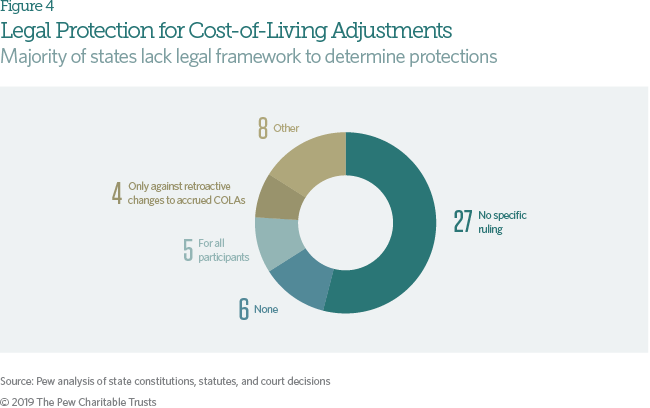

Legal protections for cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs ) are among the least-settled areas of pension law, with 27 states lacking any constitutional, statutory, or judicial authority on the issue. Six states do not protect COLAs; five do so for all participants; and four do so only for COLAs that have been accrued to date (in other words, they allow changes to future COLA accruals). The remaining eight states offer some type of limited or specific protection to COLAs in some circumstances.

Can a state’s fiscal distress justify altering benefits?

A state that treats pension benefits as contractual in nature is generally prohibited under the Contracts Clause of the U.S. Constitution from passing legislation that substantially impairs that contract. However, because states are sovereigns, they have certain rights that cannot be contracted away, such as the right to protect the health, safety, and welfare of their citizens (commonly referred to as a state’s “police power”). As a result, significant fiscal distress may allow a state to exercise its police power to make changes to pension benefits that would otherwise be unconstitutional.

The U.S. Supreme Court has developed a three-part test to determine if a state is justified in its use of the police power to impair its own contract. The test is a difficult one to satisfy and depends in part on the state’s establishing that the change was the least-drastic method of achieving an important public purpose. In the pension context, the state would need to establish that fiscal distress required a change to pension benefits and that the change made was the least-drastic means of addressing the financial condition.

To date, there have been only two reported cases that rely solely on the police power to justify otherwise unconstitutional changes to pension benefits; both were decisions of the Rhode Island Superior Court.5

In addition, state courts in Arizona and Illinois have held that the police power may never be used to justify otherwise impermissible pension changes. Both states have specific protections for pension benefits in their state constitutions, and the court read those provisions as constraining the state’s police power.6

Fiscal Distress Prompts Reform in Rhode Island

Court finds city justified in suspending COLA

Cranston Police Retirees Action Committee v. City of Cranston7 was a Rhode Island Superior Court case permitting the suspension of a 3 percent annual compounded COLA. The court first determined that the plan participants had a contractual right to the COLAs at issue and that the suspension of those COLAs constituted a substantial impairment of that contract. Even though the court found that there was a substantial impairment of contract, it also determined in this case that the city had satisfied the difficult police power test and was justified in suspending the COLA.

The plan at issue had a long history of funding shortfalls. By 2012, it was only 16.9 percent funded, with demographics that made traditional funding catch-ups challenging: Of 480 participants, only 57 were active employees; the rest were retirees. Further, the city was experiencing a general fiscal crisis, brought on in part by the Great Recession, as well as rising unemployment, devaluation of city property, two natural disasters, and reduced state aid. The city’s financial distress had resulted in a downgraded bond rating, and the city faced potential bankruptcy.8

The City of Cranston was forced to take action by the 2011 Rhode Island Retirement Security Act (RIRSA), which deemed municipal plans that were less than 60 percent funded to be in “critical” status. RIRSA required the city to inform stakeholders of this fact—and to submit a funding improvement plan to the state. If the municipality did not comply, it faced further reductions in state aid.

To develop its funding improvement plan, the City of Cranston considered more than 25 alternatives and determined that suspending the COLA was the best solution, as doing so would reduce the plan’s annual required contribution by an estimated $6 million in the first year of implementation.9 The court permitted the otherwise unconstitutional change as a valid exercise of the police power, finding that the city faced a fiscal emergency that it had neither created nor anticipated and that it had crafted a solution that did not seek to benefit one group over others. The court found that the city had sought to tailor its funding remedy as narrowly as possible and that it did not impose a drastic impairment when an evident and more moderate course would have served its purpose equally well.

The California Rule

As one of the first states to hold that public pensions create any type of contract, California has been the most influential state in developing the common-law contractual approach to public pensions. The California Rule generally provides that on the first day of employment, a contract is formed that prevents detrimental changes to the pension formula, thereby protecting even pension benefits that have not yet been earned. Specifically, the California Rule provides that “changes in a pension plan which result in disadvantage to employees should be accompanied by comparable new advantages.”10

Twelve states have adopted some form of the California Rule, although at least five of those states have made significant modifications to the rule as applied in their state. Four cases are currently pending before the California Supreme Court, challenging the standard interpretation of the rule. In addition, the court issued a decision in one case in March 2019.

Recent litigation indicates that other states are also rethinking their adherence to the California Rule. Colorado courts adopted the rule in the 1960s, stating that current employees have a “limited right” to their pensions and that any detrimental change must be offset by a comparable new advantage.11 However, in 2014, the Colorado Supreme Court held that pensions are protected as contracts only where there is clear evidence of legislative intent to form a contract.12 Based on that ruling, the Colorado Supreme Court permitted changes to COLAs, even for individuals who had already retired.

New Hampshire’s Supreme Court has similarly shifted its judicial approach to pensions. In 2012, the court appeared to adopt the California Rule in a case involving changes to the judges’ retirement plan.13 Three years later, in a case brought by participants in the New Hampshire Retirement System, the court determined that participants had no right to prevent prospective COLA changes because there was no “unmistakable” legislative intent to form such a contract.14 This apparent rejection of the California Rule appears to be a significant shift in New Hampshire’s legal approach to public pension protection.

For additional details on the California Rule, please see the appendix.

Legal protections for retiree health benefits

The law concerning retiree health benefits is less developed, and less protective, than the law governing pension benefits. In most states, these benefits are based on achieving a specific status—such as a minimum number of years of service and a minimum age—and they do not accrue or increase in value over time. In other words, if a government offers retiree health benefits for all employees who retire on or after age 55 with at least five years of service, an employee with five years of service is entitled to exactly the same benefit as an employee with 30 years of service. Additionally, the value of retiree health benefits is uncertain and varies by individual.

These distinctions often lead courts to conclude that retiree health care benefits are not earned through service in the same way as pension benefits and are therefore governed by different legal rules.

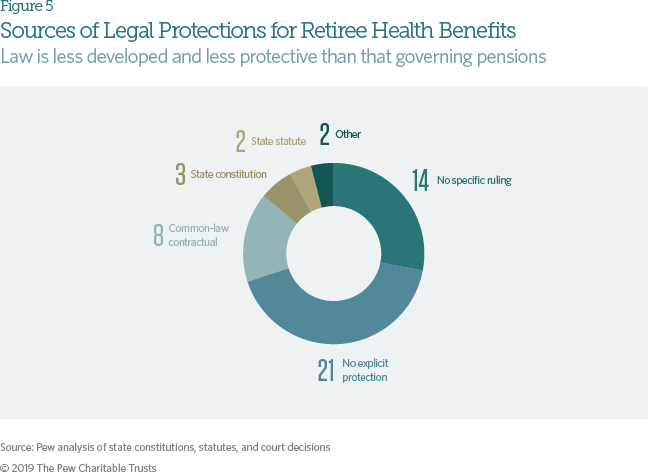

Sources of legal protections for retiree health benefits

Eight states protect retiree health benefits through the common-law contractual approach. Alaska, Hawaii, and Illinois provide protection through explicit language in the state constitution, and Kentucky and West Virginia do so through statute.

In 14 states, there is no relevant legal authority—neither judicial decisions nor statutory law—addressing the protection provided to retiree health benefits. In 21 other states, courts have held that retiree health benefits do not have any explicit protection under the law. But this does not mean that such benefits are always unprotected; it simply means there must be an explicit contract (such as a collective bargaining agreement) if such benefits are to be protected from change.

Litigation to determine legal protections for retiree health benefits

Much of the recent litigation about retiree health benefits has involved changes to an existing benefit structure. Examples of such changes include moving from a point-of-service plan to an HMO or raising required cost-sharing such as deductibles, copayments, and coinsurance amounts. The legal result often depends on the precise language used in either the formal contract or the offer of benefits. In contrast to their rulings on pension benefits, many courts have allowed changes to health benefits unless the contract terms explicitly state that the benefit structure is protected. Where the language speaks of a general right to medical benefits but contains no further qualifying language, courts tend to allow changes to the benefit structure.15 Where the offered retiree health benefits are explicitly tied to active-employee health benefits (such as, “If you are a qualified retiree, you may continue health insurance on the same terms as active employees”), any changes are generally permissible if they are also made for active employees.16

One frequently litigated issue is the duration of retiree health benefits provided through collective bargaining agreements where the contract language is silent or ambiguous regarding such duration. Where the agreement provides for retiree health benefits for eligible individuals who retire during the term of the agreement—often three years—the question is whether the right to benefits continues for the life of the individual or only until the contract expires. Some courts have held that, where the contract is silent on the duration of retiree health benefits, the benefits were most likely intended to last beyond the duration of the contract. On the other hand, some courts hold that retirees are entitled to benefits only as long as the contract is in effect, based on the position that a contract term cannot survive the expiration of the contract without explicit language supporting that.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled on the issue for the first time in 2015: In the M&G Polymers v. Tackett case, it held that where a collective bargaining agreement is silent or ambiguous regarding the duration of retiree health benefits, “a court may not infer that the parties intended those benefits to vest for life.”17 While the Supreme Court ruling answers the issue for cases brought in federal court, state courts are not bound by the holding. Nevertheless, four states have reported decisions where the state court has endorsed the Supreme Court’s holding in Tackett: New Jersey at the trial level, California at the appellate level, and Illinois and Michigan at the Supreme Court level. Notably, there are no reported state decisions rejecting the Tackett holding.

Can fiscal distress justify otherwise impermissible changes to retiree health benefits?

As with pensions, states have rarely used the police power to successfully justify changes to retiree health benefits that would otherwise be unconstitutional. The only reported case to do so involved a state statute that explicitly allowed changes to collective bargaining agreements in the event of a fiscal emergency.18

The relative absence of cases in this area is likely because many states have no reported cases of any kind addressing legal protections for retiree health care, while other states make clear that such benefits are not protected, thereby eliminating the need to resort to the police power.

Conclusion

Every state guarantees some form of legal protection for public retirement benefits, although the nature and strength of the protections vary depending on the type of benefit, the source of legal protection, the plan provisions, and employees affected by the change. Policymakers seeking to reform public retirement systems need to understand what changes are legally permitted.

Appendix A

Significant California Rule developments

California was one of the first states to hold that public pensions create any type of contract—and that the contract is formed as of the employee’s first day of employment.19 California’s adoption of a contractual framework for pension protection established a precedent that many states have followed. This was a significant advance in participant protections because states had previously treated pension benefits as a gratuity that was not entitled to any legal protection. However, current California law broadly holds not only that pension statutes create a contract but also that the contract is formed on the first day of employment and is of open duration. Thus, the pension promise protects both past and future pension accruals.

This broad protection, referred to as the California Rule, is the highest level of pension protection that has been established through court rulings. Because of this interpretation, pension benefits for current employees cannot be detrimentally changed even if the changes are only prospective.

In the past several years, five California appellate court decisions have considered whether certain changes to pension benefits were permitted, marking a significant change from long-standing interpretations of the California Rule. The California Supreme Court has granted review in each of these cases, four of which are still pending, raising the strong possibility of new guidance on the rule.20

Two of the cases still pending involve changes to county retirement systems enacted by the California Public Employees’ Pension Reform Act of 2013 (PEPRA). Among other things, PEPRA modified the definition of compensation used by county retirement systems to calculate pensions, and employees in several counties challenged the legality of those changes. Two of those lawsuits resulted in appellate court decisions: one brought by Marin County employees;21 the other a consolidated action involving Alameda, Contra Costa, and Merced counties.22 Importantly, both appellate courts agreed that there was no absolute requirement under the California Rule that a detrimental change be offset by a comparable new advantage and that the test allowed more flexibility than that. The courts agreed that reasonable changes prior to retirement are permitted and that comparable advantages “should”— not “must”—offset the detriment to employees.

While the courts agreed on this interpretation of the rule, they split on whether the changes at issue in these cases were reasonable—and therefore whether they required an offsetting benefit. The Marin court found the change at issue to be a reasonable one designed to prevent pension abuses, which did not require an offsetting advantage.23 The Alameda court emphasized that where there is no comparable advantage given to offset a detrimental change, the burden to justify the change will be “substantive.”

A recently decided pension case known as the Cal Fire case addressed PEPRA’s repeal of the ability of California Public Employee Retirement System members to purchase up to five years of pension service credit (commonly referred to as “airtime”), which the appellate court upheld. 24 As in the county cases above, the court in this case agreed that the relevant test under the California Rule is that detriments should (but not must) be offset by comparable new advantages. On March 4, 2019, the California Supreme Court announced its decision.25The court examined the statutory language and found nothing to indicate a legislative intent to form a contract protecting the right to purchase service credit in perpetuity.26 Consequently, the court did not directly address the scope of the California Rule.27

Endnotes

- Thom Reilly, “Prop 124—Changes to the Public Safety Personnel Retirement System (PSRS)” (working paper, Morrison Institute for Public Policy, Arizona State University, 2016), https://morrisoninstitute.asu.edu/sites/default/files/ariz_props_124.pdf.

- Craig Harris, “Big Prop. 124 Win to Change Public-Safety Pensions,” The Arizona Republic, May 18, 2016, http://www.azcentral.com/story/news/politics/elections/2016/05/18/big-prop-124-win-change-public-safety-pensions/84459132.

- Christensen v. Minneapolis Municipal Employees Retirement Board, 331 N.W.2d 740 (Minn. 1983), https://www.courtlistener.com/opinion/1614244/christensen-v-mpls-mun-emp-retire-bd.

- Booth v. Sims, 456 S.E.2d 167 (W. Va. 1995), https://www.courtlistener.com/opinion/1253086/booth-v-sims.

- Cranston Police Retirees Action Comm. v. City of Cranston et al., C.A. No. KC-13-1059 (R.I. Super. Ct. 2016), https://law.justia.com/cases/rhode-island/superior-court/2016/13-1059.html; Andrews et al. v. Lombardi et al., C.A. No. KC-13-1128, 13-1129 (R.I. Super. Ct. 2017), https://law.justia.com/cases/rhode-island/superior-court/2017/13-1128-0.html.

- Fields v. Elected Officials’ Retirement Plan, 320 P.3d 1160 (Ariz. 2014) https://www.leagle.com/decision/inazco20140220000; In re Pension Litigation, 32 N.E.3d 1 (Ill. S. Ct. 2015), https://www.leagle.com/decision/inilco20150508163.

- Cranston.

- Ibid.

- Gregory Smith, “Cranston’s Pension Overhaul Will Save City Millions, but Court Challenge Remains,” Providence Journal, Feb. 8, 2014, http://www.providencejournal.com/breaking-news/content/20140208-cranstons-pension-overhaul-will-save-city-millions-but-court-challenge-remains.ece.

- Betts v. Board of Administration of the Public Employees’ Retirement System et al., 21 Calif.3d 859, 864 (1978) (internal citations omitted), https://scocal.stanford.edu/opinion/betts-v-board-administration-30508; citing Allen v. City of Long Beach, 45 Calif.2d 128, 131 (1955), https://scocal.stanford.edu/opinion/allen-v-city-long-beach-26585.

- Police Pension and Relief Board of City and County of Denver v. Bills, 366 P.2d 581 (Colo. 1961), https://law.justia.com/cases/colorado/supreme-court/1961/19659.html.

- Justus v. State, 336 P.3d 202 (Colo. 2014), https://www.leagle.com/decision/incoco20141020035.

- Cloutier v. State, 42 A.3d 816 (N.H. 2012), https://casetext.com/case/cloutier-v-state-4.

- American Federation of Teachers v. State, 111 A.3d 63 (N.H. 2015), https://www.leagle.com/decision/innhco20150116251.

- See, e.g., Dannenberg v. State, 383 P.3d 1177 (Hawaii 2016), https://casetext.com/case/dannenberg-v-state-1.

- See, e.g., St. Louis Police Officers’ Association v. Board of Police Commissioners of the City of St. Louis, 259 S.W.3d 526 (Mo. 2008).

- M&G Polymers USA v. Tackett et al., 135 S. Ct. 926 (2015), https://www.leagle.com/decision/insco20150123k82. This case was followed in CNH Industrial N.V. et al. v. Jack Reese et al., 138 S. Ct. 761, 583 U.S. _____ (2018), https://www.leagle.com/decision/insco20180220n29.

- Welch v. Brown, 935 F. Supp. 2d 875 (E.D. Mich., 2013), https://casetext.com/case/welch-v-brown-2.

- Amy Monahan observes that the notion of pension rights as contractual rights became law through a single sentence of dictums in a California Supreme Court opinion describing pensions as a form of deferred compensation that is, therefore, “in a sense” part of the contract of employment. See Amy Monahan, “Statutes as Contracts? The ‘California Rule’ and Its Impact on Public Pension Reform,” Iowa Law Review 97 (2012): 1046, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1933887.

- Marin Association of Public Employees et al. v. Marin County Employees Retirement Association et al., 206 Calif. App. 5th 674, 206 Calif. Rptr. 3d 3365, rev. granted 383 P.3d 1105 (Calif. 2016); Cal Fire Local 2881 et al. v. California Public Employees’ Retirement System, 7 Calif. App. 5th 115, 212 Calif. Rptr. 3d 471 (Calif. Ct. App. 2016), rev. granted 391 P.3d 1190 (Calif. 2017); Alameda County Deputy Sheriff’s Association et al. v. Alameda County Employees’ Retirement Association et al., 413 P.3d 1132 (Calif. 2018), https://law.justia.com/cases/california/court-of-appeal/2018/a141913.html. While Marin was the first case granted review, further action was deferred pending the result in the Alameda and Cal Fire appellate court cases.

- Alameda at 791.

- Marin County at 833.

- The court also noted that the change at issue did come with an offsetting advantage to employees, in that pension contributions would no longer be taken out of the excluded compensation, thereby resulting in a larger paycheck for affected employees.

- Cal Fire Local 2881 v. California Public Employees’ Retirement System, 7 Calif. App. 5th 115 (2016), https://www.leagle.com/decision/incaco20161230019.

- Cal Fire Local 2881 v. California Public Employees’ Retirement System, __ Calif. App. ____ (2019), https://www.courts.ca.gov/opinions/documents/S239958.PDF.

- Judicial Branch of California, “Dec. 5, 2018 Oral Argument Cases,” http://www.courts.ca.gov/41490.htm.

- The California Supreme Court has also assumed jurisdiction in Hipshire v. Los Angeles County Employees Assn., 24 Calif. App. 5th 740, https://www.leagle.com/decision/incaco20180619033#; and McGlynn v. State of California, 21 Calif. App. 5th 710, https://casetext.com/case/mcglynn-v-state-15. Both are related to the California Rule.