New Maps Show U.S. Rivers With High Natural Values

Data can help inform decisions on dam removal and protection measures

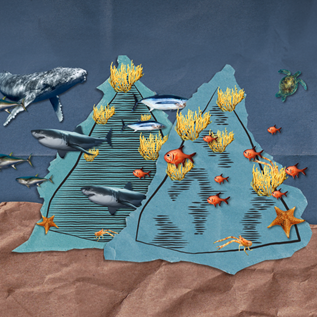

Several Indigenous communities around the world speak of freshwater systems as “living waters,” testament to the life-giving and sustaining value of rivers, lakes, wetlands, bogs, and more. Freshwater bodies are home to a plethora of species and some of the highest concentrations of biodiversity on the planet, and they nourish and replenish people around the globe. But many of these waters are also at risk, facing threats that experts expect to worsen with climate change and increasing human pressures.

To help policymakers, elected officials, and other stakeholders here in the United States make better-informed decisions on where and how to address the threats to our waters, The Pew Charitable Trusts engaged NatureServe and Michigan State University to build national databases of watershed conditions and barriers that alter the natural flow of rivers, streams, and other freshwater bodies.

The first database includes assessments and analyses of biodiversity, ecological conditions, and degrees of protection for freshwater systems within the continental U.S. The second database provides a wealth of information that can be used to assess the potential benefits and drawbacks of removing obsolete or dangerous dams across the country. Policymakers can use these maps to help determine how best to leverage resources to safeguard rivers.

And protecting these resources is critical for a variety of reasons. Rivers, lakes, and wetlands transport nutrients, minerals, and fine sediments from the mountains to the ocean and facilitate the reverse transfer of nutrients—through migrating species such as salmon, sturgeon, and river herring—from the sea back to higher terrestrial elevations. At the same time, these systems provide clean drinking water, flood control, shoreline stabilization, and carbon sequestration and support industrial, transportation, and agricultural activities, along with fisheries and tourism.

As for the threats to freshwater resources, many lakes, rivers, and wetlands in the United States have been so severely damaged that their overall health is declining at a much faster rate than terrestrial ecosystems. For example:

- One-third of the nation’s wetlands have been lost since this country was colonized. In the Lower 48 states, over 50% have been lost.

- More than 90,000 dams and untold numbers of culverts and diversions block our nation’s rivers.

- In the Southeast, 28% of fishes, more than 48% of crayfishes, and more than 70% of mussels are threatened with extinction.

Fortunately, freshwater systems have enormous capacity for restoration and resilience. River and wetland protection and dam removal can rapidly deliver benefits, such as supporting human health and conserving species and habitats, across watersheds and well beyond the banks of the protected waterway. We hope these interactive database maps will add to the growing understanding of the nation’s vital waterways and result in science-based actions that will ensure their restoration and conservation for generations to come.

Nicole Cordan oversees river protection and restoration work for The Pew Charitable Trusts’ U.S. public lands and rivers conservation project.