More Opioid Treatment Programs Needed to Help People Recover From Addiction

Pew recommends state and federal policies to increase access to quality care at these facilities

Across the United States, about 1.6 million people struggle with opioid use disorder (OUD), a chronic disease that includes addiction to heroin and prescription painkillers such as oxycodone. Methadone is a lifesaving medication for treating OUD; expanding access to the drug is critical to addressing the opioid crisis.

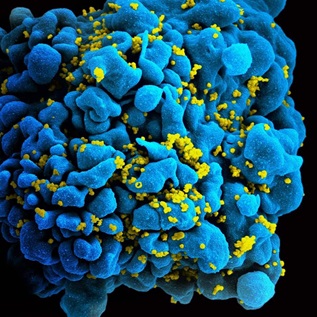

Decades of research demonstrate that methadone and two other Food and Drug Administration-approved medications reduce overdose deaths, illicit opioid use, and the transmission of infectious diseases such as hepatitis C and HIV. However, methadone can be dispensed only by opioid treatment programs (OTPs), which must also provide counseling and can offer a range of other services and additional medications for OUD. As of March 2019, about 409,000 patients were receiving methadone treatment and, as of July 2021, 1,836 OTPs were operating across the U.S.

But OUD—and even the medications proven to help manage the disease—is highly stigmatized. Some policymakers, health care providers, and even patients themselves still view addiction as a moral failing and not a chronic medical condition. As a result, many barriers to treatment exist. A new issue brief from The Pew Charitable Trusts offers the following recommendations for federal and state policymakers so they can reduce these barriers.

Establish more opioid treatment programs

Federal and state rules tightly control where OTPs can be established, when and how they can dispense medications, what services they must offer, and which professionals they must employ to oversee treatment. These regulations are intended to protect patients and communities, but they can be overly burdensome. To strike a better balance between safety and access:

- State lawmakers should eliminate legal obstacles that prevent the creation of new OTPs, including limits on where facilities can operate. Some states, for example, require that OTPs have pharmacists on staff, which is not required by federal law.

- State behavioral health agencies and Medicaid programs should consider adopting innovative OTP models such as the “hub and spoke” approach, which creates two levels of care (hubs for individuals with acute needs and spokes for stable patients) to better meet the individualized needs of patients. As the first state to use this system, Vermont achieved the highest per capita treatment capacity for OUD patients in the country in 2016. Ohio facilitated the expansion of mobile medication units, which act as satellite OTP sites to serve the state’s harder-to-reach populations at locations such as homeless shelters, jails, prisons, boards of public health, and rural Appalachian counties.

Facilitate access to methadone

In many cases, patients must wait weeks to be enrolled in an OTP, during which time medication is not yet available. And even after that lengthy process, they then must visit the clinic in person, typically daily, to receive their medication. This can be prohibitively difficult, especially when people live far away or have conflicting responsibilities such as work or child care. To enable more patients to benefit from methadone:

- Federal and state policymakers should allow patients to access medication for up to 120 days as they await placement in an OTP.

- Federal and state policymakers should allow OTPs more flexibility to dispense methadone to more patients and for longer periods (for example, a month’s supply) for use at home so that patients don’t have to come back every day. During the COVID-19 pandemic, federal and state regulators relaxed take-home requirements for methadone to limit face-to-face contact at treatment facilities. Though research is still accumulating, there was no observed increase in abuse of these policies. As a result, these policies should remain in place even after the pandemic.

Expand Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement and increase the number of participating OTPs

OUD disproportionately affects people eligible for Medicare (older adults and individuals with disabilities) and Medicaid (individuals earning lower incomes). Although both programs currently cover treatments for OUD, the requirement that all Medicaid programs do so is temporary. Further, many OTPs do not accept reimbursement from these programs. To reduce the financial burden of treatment on patients:

- Congress should require every state Medicaid program to permanently cover all medications for OUD. Otherwise, the requirement will expire in October 2025, at which point tens of thousands of people with OUD could lose access to vital medications they need to stay in treatment.

- Federal and state policymakers should incentivize OTPs to participate in both programs, and start by researching which OTPs do not participate and why.

OTPs—and the medications they dispense—work. Federal and state policymakers have several opportunities to increase access to both and help thousands more Americans recover from OUD.

Ian Reynolds is a senior manager and Vanessa Baaklini is an associate with The Pew Charitable Trusts’ substance use prevention and treatment initiative. Josh Wenderoff is an officer with Pew’s health programs.

America’s Overdose Crisis

Sign up for our five-email course explaining the overdose crisis in America, the state of treatment access, and ways to improve care

Sign up