Despite Diminishing Federal Aid, Total Personal Income Beat Last Year’s

Note: This data has been updated. To see the most recent data and analysis, visit Fiscal 50.

Total personal income was higher in every state in the third quarter of 2020 than a year earlier, with substantial but tapering government aid supporting individuals and businesses as the coronavirus pandemic continued to stifle economic activity. Without government assistance, personal income would have been lower than a year earlier in the majority of states.

Six months into the pandemic, two major factors drove increases in the sum of residents' personal income: robust government assistance and earnings, which rebounded somewhat from a steep decline in the second quarter. But the third quarter’s year-over-year gains were smaller than the substantial growth recorded in the second quarter, when an initial infusion of relief funds jolted this key economic indicator.

Government aid remained the primary growth driver, as temporary relief programs and benefits such as unemployment insurance and Medicaid continued to stabilize state economies during the pandemic. If not for government transfers to sustain total personal income, 27 states would have experienced overall declines, compared with all 50 in the previous quarter.

Earnings—which include wages from work and extra compensation such as employer-sponsored health benefits, as well as business profits—were higher than a year ago in 29 states as the economy began to recover from historic losses and more businesses reopened their doors.

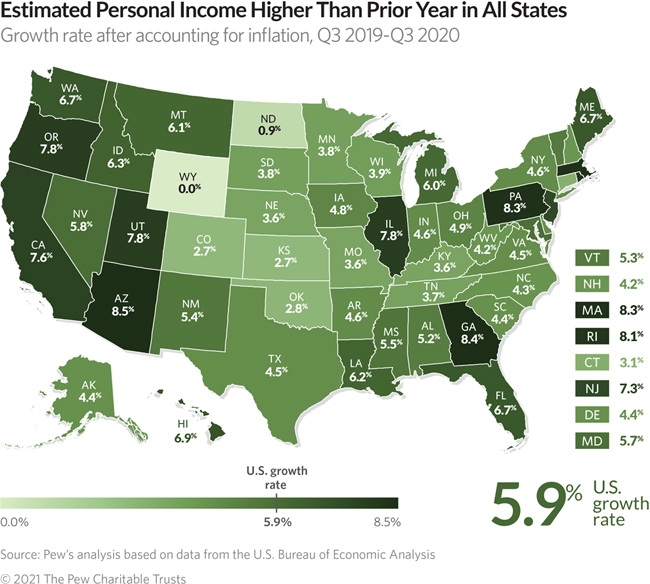

Total personal income grew 5.9% nationwide in the third quarter compared with a year earlier— an annualized $1.1 trillion, after adjusting for inflation—with Arizona and Georgia recording the top year-over-year increases. North Dakota, Wyoming, and other energy-producing states, meanwhile, experienced much weaker growth.

Nationally, government transfer payments dropped about 24% from the second quarter, after accounting for inflation, but remained unusually high. Combined state and federal government assistance dipped after declining unemployment levels reduced the number of individuals claiming benefits, most eligible Americans exhausted their stimulus payments, and some supports expired. Year-over-year increases in government assistance ranged from about 18% in Mississippi to nearly 77% in Hawaii, mirroring upticks in unemployment rates.

Earnings rebounded in some states as more Americans returned to work. Nationally, earnings in the third quarter increased by about $65 billion from a year earlier based on inflation-adjusted annualized data, a marked turnaround from the $670 billion loss in the second quarter. Pandemic-induced layoffs and business closures in the second quarter had triggered declines in earnings across all states, while in the third quarter just 21 experienced a drop compared with a year earlier, reflecting better economic conditions. Utah led all states with annualized earnings growth of 6.7%, while Hawaii incurred the steepest loss of 7.3% as its tourism industry continued to struggle.

State personal income—a measure used to assess economic trends—matters to state governments because tax revenue and spending demands may rise or fall along with residents’ incomes. It sums up all the money and benefits that residents receive from work, certain investments, income from owning a business and property, as well as benefits provided by employers or the government, including the extra federal aid provided in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Results for the third quarter of 2020 are based on estimates and subject to revision, as is Pew’s ranking of growth rates for state personal income.

State highlights over the past year

The third quarter of 2020 reflected a recovering economy after the pandemic and ensuing recession led to widespread business closures and layoffs earlier in the year. A comparison of estimated annualized growth rates in each state’s total, inflation-adjusted personal income between the third quarter of 2020 and a year earlier (subject to data revisions) shows:

- Arizona (8.5%) had the highest growth rate in the sum of all its residents’ personal income of any state, followed by Georgia (8.4%), Massachusetts and Pennsylvania (both 8.3%), and Rhode Island (8.1%). Georgia and Arizona were among states with the largest increases in earnings, and Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island had some of the largest increases in transfers.

- Wyoming’s total personal income remained essentially unchanged, while North Dakota recorded only a modest increase (0.9%). Both were among only five states recording growth rates below 3%.

- In seven states—California, Hawaii, Illinois, Massachusetts, Nevada, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania—government transfer payments increased by at least 50% from a year ago.

- Among the 29 states with higher earnings than a year earlier, the strongest gains were in Utah (6.7%), Florida (5.7%), and Idaho (5.3%). The sharpest losses were registered in Hawaii (-7.3%), Wyoming (-3.8%), Nevada (-3.8%), and North Dakota (-3.7%).

States Recovered Unevenly From the Great Recession

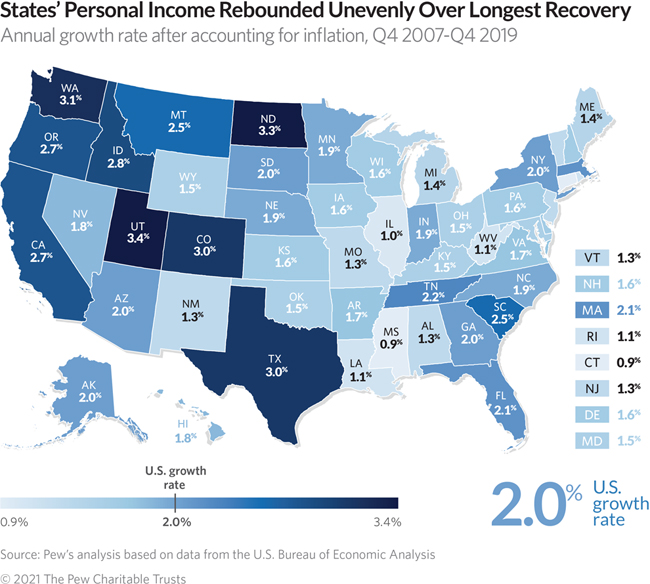

States entered the new recession from vastly different starting points in terms of personal income growth over the longest economic recovery in U.S. history. Inflation-adjusted personal income eventually bounced back in all states from the Great Recession, but at different paces. From the start of the 2007-09 downturn through the fourth quarter of 2019—the last quarter before the coronavirus pandemic started to derail the economy—Utah and North Dakota led all states with long-term compound annual growth rates equivalent to 3.4% and 3.3% a year, respectively, followed by a group of mostly Western states. Connecticut and Mississippi lagged all other states with pre-pandemic growth rates equivalent to 0.9% a year, less than half of the U.S. rate of 2%. These compound annual growth rates represent the pace at which state personal income dollars would need to grow each year to reach their current level, after accounting for inflation.

Alaska and North Dakota were the first states in which total personal income bounced back from its losses, in late 2009, just over two years after the onset of the Great Recession. It wasn’t until the fourth quarter of 2014, seven years after the start of the recession, when the last state—Nevada—recovered. In most states, it took about three years for the aggregate personal income to get back to pre-Great Recession levels, after accounting for inflation.

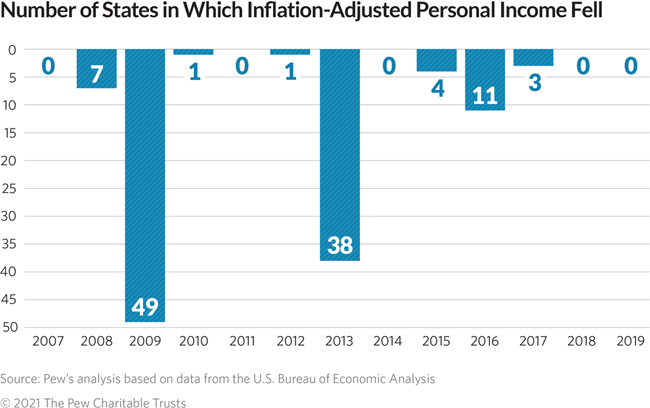

Although the use of compound annual growth rates allows for comparisons of states’ economic performance over several years, personal income did not actually change at a steady pace, instead falling in some years and rising in others, based on recently revised data.

No state escaped the Great Recession without a calendar-year drop in total personal income, but a handful of states can boast only one decrease, in 2009: Colorado, Idaho, Illinois, Mississippi, Utah, and Washington. The longest recovery on record ended on a high note with every state reporting calendar-year increases in personal income in 2018 and 2019.

What is personal income?

Personal income sums up residents’ paychecks, Social Security benefits, employers’ contributions to retirement plans and health insurance, income from rent and other property, and benefits from public assistance programs such as Medicare and Medicaid, among other items. Personal income excludes realized or unrealized capital gains, such as those from stock market investments.

Federal officials use state personal income to determine how to allocate support to states for certain programs, including funds for Medicaid. State governments use personal income statistics to project tax revenue for budget planning, set spending limits, and estimate the need for public services.

Growth in personal income should not be interpreted solely as wage growth; wages and salaries account for about half of U.S. personal income. Likewise, growth in total state personal income should not be seen as a measure of how much the income of average residents has changed. Other measures should be used to approximate income growth for individuals, such as state personal income per capita or household income.

Looking at state gross domestic product, which measures the value of all goods and services produced within a state, would yield different insights on state economies.

Download the data to see state-by-state growth rates for personal income from 2007 through the third quarter of 2020. Visit Pew’s interactive resource, “Fiscal 50: State Trends and Analysis,” to sort and analyze data for other indicators of state fiscal health.