To Protect Vast Area of Pacific Ocean From Seabed Mining, International Body Should Strengthen Rules

New safeguards for biodiverse Clarion-Clipperton Zone will help, but lack crucial details

Seabed mining operations are likely to have impacts beyond the area of a specific mine site. Sediment plumes, noise and the destruction of vulnerable marine habitat may spill across a region. Consequently, such mining should not go forward without policies in place to protect the environment at a regional scale. One way to accomplish that is through regional environmental management plans (REMPs), key tools that the International Seabed Authority (ISA) uses to ensure large parts of the ocean are managed and monitored holistically. Among other measures, REMPs outline areas in which no mining is permitted, known as areas of particular environmental interest, or APEIs.

Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, the ISA must regulate all mining-related activities on the sea floor in areas beyond national jurisdiction. The ISA is developing a mining code that would govern deep-sea mineral extraction—should that activity move forward—and recently approved four new APEIs in the Pacific Ocean totalling around 518,000 square kilometres (200,000 square miles), as part of a revised plan for the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ).

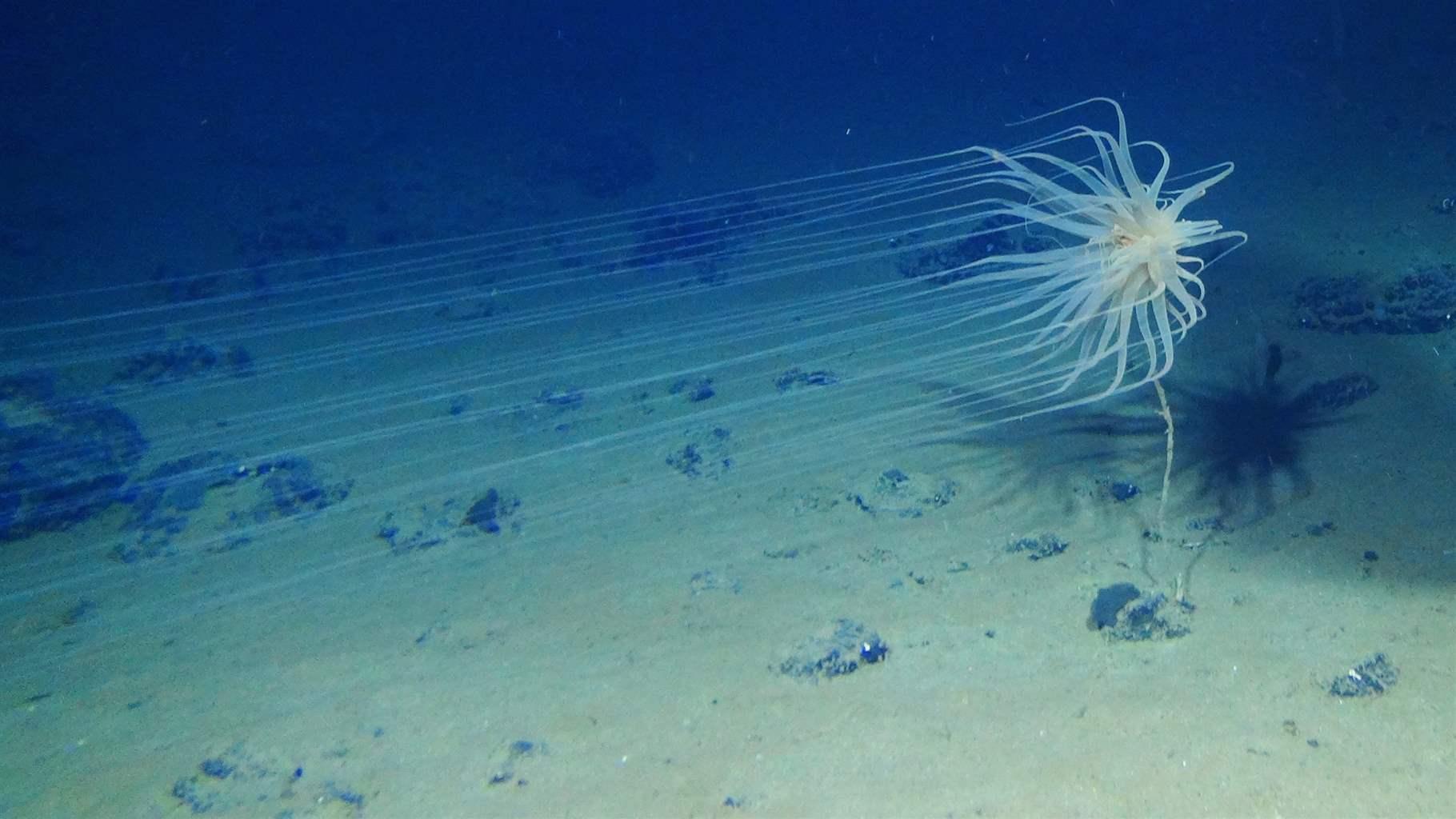

The CCZ is an expanse of 4.5 million square kilometres (1.7 million square miles) stretching between Hawaii and Mexico, an area as wide as the continental United States and composed of an abyssal plain punctuated by seamounts. Atop the muddy seabed lie trillions of potato-sized polymetallic nodules that contain potentially valuable minerals. These nodules are also home to a variety of wildlife, including the dumbo octopus, sponges and xenophyophores—single-celled protists the size of a baseball that grow on stalks from the nodules.

The ISA approved the current CCZ plan in 2011, with a required review every two to five years. Regular review of every REMP helps ensure management is responsive and adapts to current knowledge and up-to-date data. The plans should be a vital part of protecting the deep sea by offering geographically targeted environmental protections in the form of regional management goals, thresholds for mining impacts such as noise and plumes, consideration of cumulative impacts and provisions for protected areas. Since ocean ecology varies from place to place and over time, regional plans need to be location specific and adaptable.

The new APEIs in the CCZ improve protection of nodule-rich habitats at the core of the zone. These APEIs will increase the representativity (ensuring different types of habitats are protected) and connectivity, (such as ensuring wildlife populations can procreate) of the CCZ’s nine existing APEIs, and bring the total area protected to more than 1.9 million square kilometres (760,000 square miles).

The CCZ plan also requires that environmental baseline data is updated, cumulative impacts considered, best available techniques implemented and guidelines established, though the REMP is unclear on who is responsible for these things. But for the new APEIs to be as effective as possible, various elements of the CCZ plan still need to be developed or encoded, including:

- Establishing how long APEIs are in place—for example, until mining effects are no longer present.

- Requiring ongoing evaluation of the APEI network’s effectiveness, including continued collection and analysis of data.

- Standardizing and establishing quality control of the data stored in the ISA’s global database, called DeepData.

- Setting thresholds for ecological indicators, such as measurements of biodiversity and ecosystem health, to assess harm to the natural world based on regional environmental goals and not on mining contractors’ goals.

- Creating a coherent monitoring plan across the region.

- Developing a plan for establishing and monitoring areas affected by mining and analyzing how they compare with areas left alone.

- Requiring timely and transparent submission of mining contractors’ data and reports.

- Considering region-specific rules under each plan to govern mining where it is permitted.

The ISA must also ensure that the CCZ plan is regularly reviewed so that these needed actions occur. ISA member States Germany and the Netherlands, with co-sponsorship from Costa Rica, have proposed such a review. This proposal recommends establishing a committee of technical experts for each plan; that body would review the plan annually, provide a report to the ISA Council—the authority’s rulemaking body—summarizing new environmental data from mining contractors and scientific literature, including monitoring data, and create recommendations based on this new knowledge.

At the same time, the ISA should adopt a standardized creation process for environmental plans—with clear monitoring and review provisions—at its next opportunity, and should review and strengthen the CCZ plan to ensure that the Pacific deep-ocean ecosystem and the marine life that calls it home are protected if seabed mining moves forward in the future.

Megan Jungwiwattanaporn works on cross-campaign efforts within The Pew Charitable Trusts’ conservation work.