To Curtail Illegal Fishing, Atlantic Ocean Tuna Managers Should Make It Harder to Hide

Oversight body’s meeting offers chance to require transparency of vessel activity, ownership and more

Tuna fisheries in the Atlantic Ocean provide food, income and employment for communities in more than 50 countries on five continents. Managing these fisheries—which are worth billions of dollars each year—falls to the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT), which has numerous opportunities to act against illegal fishing at its virtual annual meeting 15-23 November.

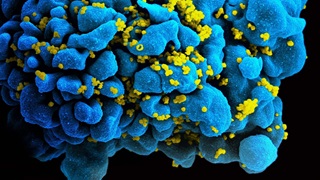

Illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing threatens sustainable fishing, slows the rebuilding of overfished populations and adversely affects the livelihoods of law-abiding fishers and others who depend on a healthy ocean. The ICCAT should take these actions at its meeting to ensure that all tuna sold to consumers was caught legally and in a well-regulated environment.

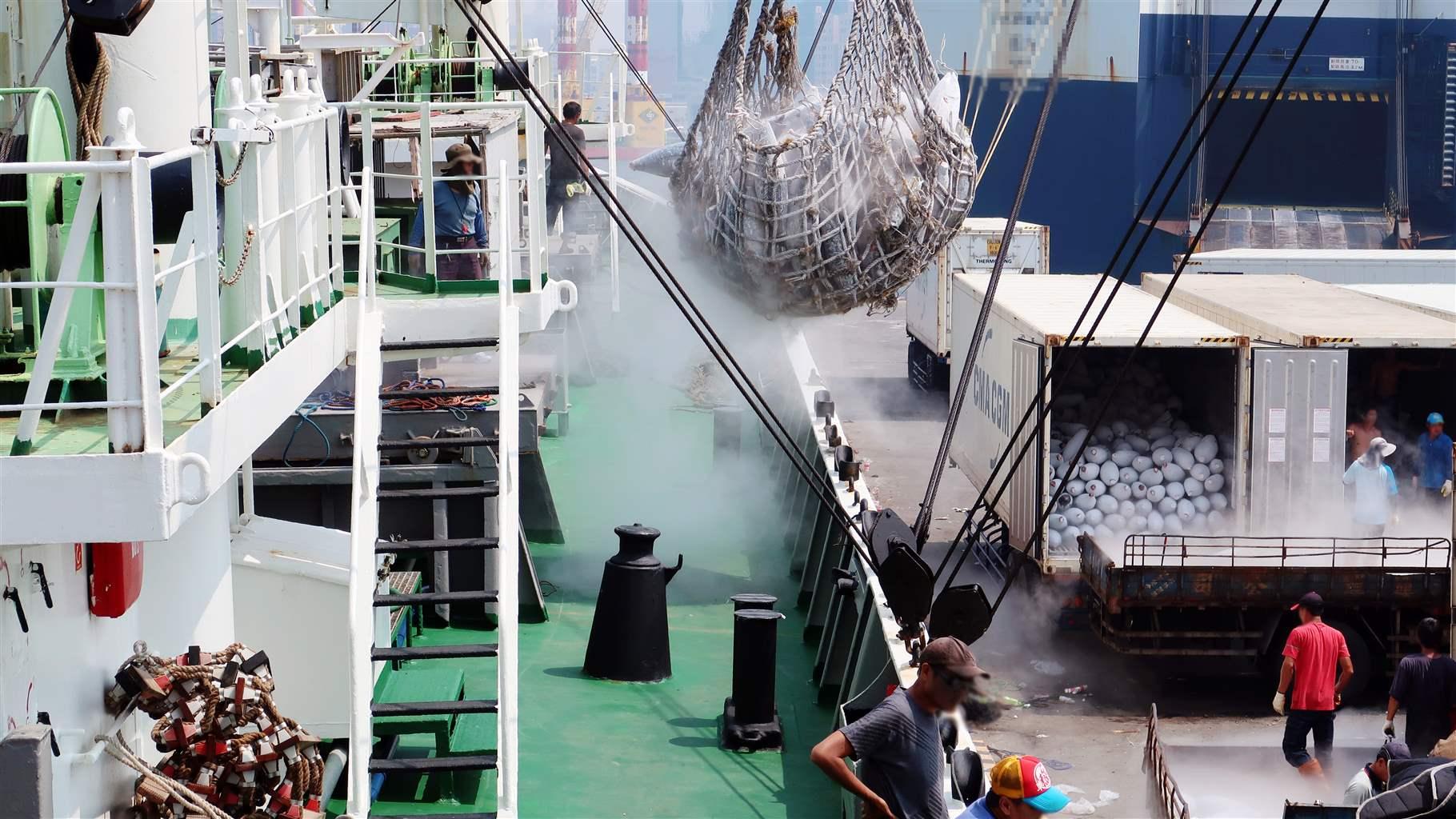

Improve management of transshipment in the Atlantic Ocean

Transshipment, or the transfer of catch from a fishing vessel to a carrier ship, is a common practice used by longline fleets to reduce operational costs and maximize their time fishing. But transshipment also provides an opportunity for bad actors to launder illegally caught tuna, shark and swordfish by mixing it with catch from vessels that have followed the rules. Not only is that unfair to those legal operations, but it fosters conditions for other illicit activities, such as human trafficking, and potentially deceives consumers who trust that they are buying legal products.

In June, the United States presented ICCAT with a proposal to overhaul transshipment management, drawing a mix of support and suggestions for improving the proposal from other delegations. In response, the U.S. has submitted an updated proposal that would close several loopholes and make ICCAT the first tuna regional fisheries management organization in several years to decisively reform transshipment management.

Among other things, the proposal would increase reporting of and verification requirements for transshipment data, prohibit transshipment to vessels flagged to non-member States, require that carrier ships and fishing vessels that transship share their location tracking information with ICCAT’s Secretariat, and encourage ICCAT to consider additional observer coverage or electronic monitoring on longline vessels that transship. Under the proposal, managers would increase oversight of transshipment and greatly reduce opportunities for bad actors to get IUU fish into the legal supply chain.

Increase transparency of vessel activity

ICCAT should move to swiftly adopt two additional proposals on the table at the November meeting. An EU proposal aims to reduce illegal activity by preventing ICCAT members—including any entities or people operating within those States—from engaging in or benefiting from IUU fishing. This would help prevent IUU fishers from changing their vessel registration—a common practice to evade detection by authorities—and would prevent individuals not directly engaged in fishing (for example, those involved in banking and insurance industries) from benefiting from IUU activity.

Another proposal, cosponsored by the European Union and the U.S., would require more ICCAT vessels to obtain a unique identification number from the United Nations International Maritime Organization (IMO). Currently, vessel owners can easily change the names or flag of registration of their boats, making it difficult for authorities—or ICCAT—to enforce rules.

Issued for free, IMO numbers are similar to a car’s vehicle identification number and are considered the gold standard of unique vessel identifiers. Once issued, an IMO number stays with a vessel throughout its life, so enforcement and compliance officers can be confident about which vessels they are dealing with. Currently, ICCAT requires IMO numbers for only a subset of its vessels. The IMO recently moved to increase eligibility for the numbers, so ICCAT should now require that more eligible vessels obtain IMO numbers. The cosponsored proposal would accomplish this goal.

ICCAT has focused on stock management at its recent meetings, but management can be effective only if the rules are implemented and followed. By adopting the proposals outlined above, ICCAT can give Atlantic tuna fisheries some of the strongest oversight among internationally managed fisheries in the world. And that’s a status that the ocean, its fish and the communities that rely on them all deserve.

Grantly Galland works on The Pew Charitable Trusts’ international fisheries project.