Vital Coastal Areas Benefit From Federal-State Partnerships

Nationwide program helps species, habitat, researchers, and communities

In 2017, after Hurricane Irma devastated the northeastern Caribbean and Florida Keys, the storm took aim at Marco Island, along Florida’s southwestern coast. Although the area braced for the worst, coastal wetlands, including those in the nearby Rookery Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve, blunted the hurricane’s forces and reduced the toll on Marco Island and mainland communities.

“We’ve seen it here in south Florida, the importance of forests and wetlands related to storm surge and hurricane protection,” Robert R. Twilley, executive director of Louisiana Sea Grant and a Louisiana State University professor, told PBS in a documentary about Rookery Bay. Twilley’s doctoral dissertation focused on the reserve. “They can knock down waves, they can protect shorelines from erosion, they can protect housing behind the trees.”

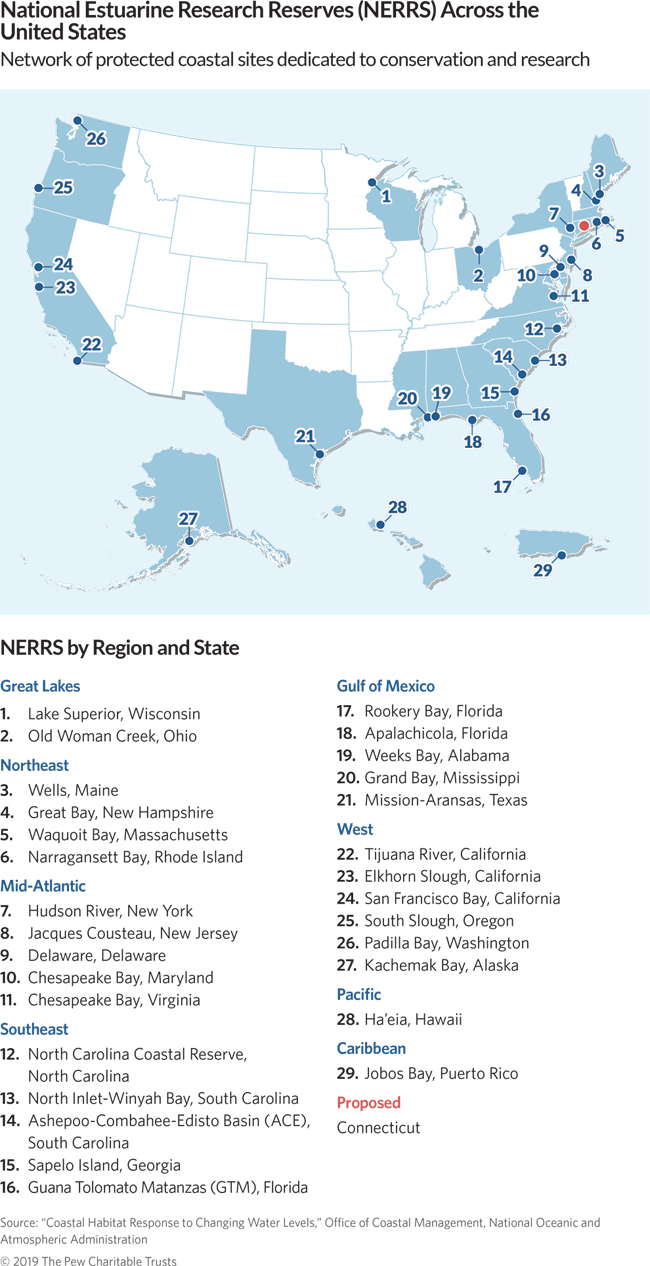

Rookery Bay is one of 29 estuaries in 24 states in the National Estuarine Research Reserve System (NERRS). Estuaries are vibrant, but vulnerable, areas along the coasts where freshwater flowing from rivers and streams mixes with saltwater from the ocean and bays. The mangroves, salt marsh, seagrass, and upland areas found in and around estuaries buffer developed areas from storms and provide habitat for a diversity of wildlife, including fish, shellfish, and seabirds. Together, these habitats and animals define and sustain much of the country’s coastal and Great Lakes regions.

Congress established NERRS in the early 1970s as part of the Coastal Zone Management Act, which promotes and relies on strong federal-state partnerships to balance shoreline development and conservation, while fully considering the “ecological, cultural, historic, and esthetic values” of these unique areas.

NERRS guidelines for implementing the program call for reserve sites across 29 distinct biogeographical subregions along the coasts and Great Lakes. Today, 20 of those subregions have at least one site, and some have multiple. The areas range from less than one square mile, such as Old Woman Creek in Ohio, to 581 square miles, in Kachemak Bay, Alaska. Together they cover more than 2,000 square miles of coastal habitat.

The 2017-22 NERRS strategic plan calls for the reserve system to expand to ensure that varied estuarine types are part of the system.

Protection is only one goal

The process of establishing a NERRS site begins when a state governor submits a letter of interest to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). If NOAA determines it can accept a new site in the system, it provides up to $100,000 in matching federal funds to help the state identify a site and develop a detailed management plan through a public process.

Once the secretary of commerce—who oversees NOAA—designates a reserve, it generally fulfills five missions:

- Monitoring. Each site collects data on factors such as water quality, weather, flora and fauna, habitat, and land use and cover. Often researchers at NERRS locations use standardized collection and analysis procedures to help ensure data are easy to compare. Information from across the system is then shared among experts to improve assessments and management of U.S. estuaries.

- Public education. Reserves function as outdoor classrooms that provide hands-on education for students, teachers, and others on topics ranging from climate change to the importance of native plants and wildlife.

- Research. Each site is expected to serve as a living laboratory where investigators study the effects of development, climate change, invasive species, storms, and more on coastal communities.

- Stewardship. Through programs and outreach, reserves foster an understanding of the need to conserve estuaries and responsibly manage coastal areas.

- Training. The system’s Coastal Training Program helps scientists and educators develop curricula on issues important to coastal management.

At the same time, each NERRS reserve site has unique characteristics, and their managers have leeway to focus on locally relevant issues. And visitors to reserves can engage in recreational activities, such as fishing, kayaking, boating, bird-watching, hunting, hiking, and swimming.

The Pew Charitable Trusts recognizes the value NERRS offers to our nation’s coastal areas, which is why we support the program’s goal of expanding this vital system to help ensure that it represents the broad biodiversity of America’s coastal estuaries.

Ted Morton directs The Pew Charitable Trusts’ efforts at the federal level to protect ocean life and coastal habitats.

America’s Overdose Crisis

Sign up for our five-email course explaining the overdose crisis in America, the state of treatment access, and ways to improve care

Sign up

5 Missions of National Estuarine Research Reserve System