Insights From Fiscal 50's Key Measures of State Fiscal Health

Recovery from the Great Recession is slow and uneven

States’ fiscal conditions have improved since the Great Recession ended six years ago, but their recoveries are incomplete. More than 20 states still collect less tax revenue than at their recession-era peaks, after adjusting for inflation, and most have yet to rebuild their financial cushions to pre-recession levels. In addition, 22 states’ employment rates trail 2007 levels. Despite these challenges, personal income in all states has bounced back above pre-recession figures, though growth has fallen short of historic norms.

- Tax revenue. Nationally, total state tax revenue recovered more than two years ago from its plunge during the recession. But state to state, the recovery has been uneven due to differences in economic conditions as well as tax policy choices. For the first time, tax collections in a majority of states—29—were higher in the second quarter of 2015 than at their peaks before or during the downturn, after adjusting for inflation. States with below-peak tax revenue still have less purchasing power than they did more than six years ago.

- Reserves and balances. States have only partially rebuilt their financial cushions after tapping them to plug budget gaps during the recession. At the end of fiscal year 2015, only 18 states could cover more government expenses using rainy day funds and general fund balances than they could have in fiscal 2007, just before the recession. Four states had less than five days’ worth of expenses set aside for budget shortfalls.

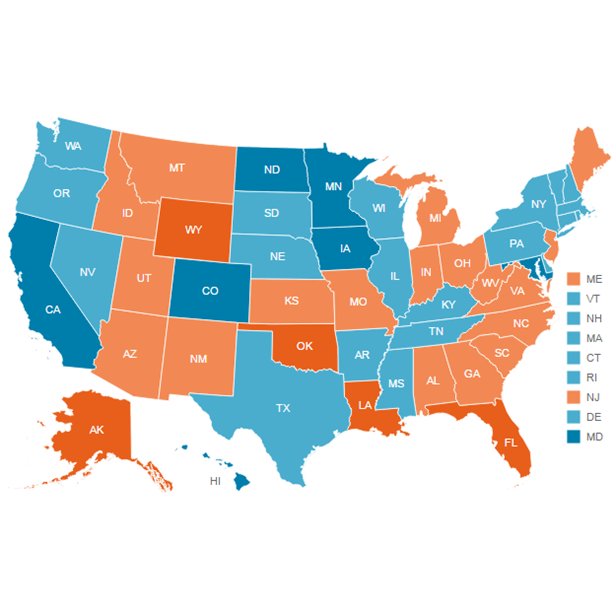

- Employment-to-population ratio. Despite a U.S. economy that has added jobs each month over the past five years, no state could boast that its core labor pool had fully recovered as of 2015. The share of prime-working-age adults (ages 25 to 54) with a job remained below prerecession levels nationally and in 22 states. Employment rates for this population were lower than in 2007 in another 26 states and higher in two, but not by statistically significant amounts, so the results were inconclusive.

- State personal income. Personal income in all states is back above levels seen at the Great Recession’s onset, signaling a widespread U.S. economic recovery. But growth since the start of the recession has varied, ranging from a constant annual rate of less than 1 percent in Nevada to more than 5 percent in North Dakota. Only one state—North Dakota—lost some of its post-recession gains in the past year.

Over the long term, additional challenges await states

Even after overcoming the effects of the recession, states face financial pressures that will shape budgets now and for years to come. A major issue for a number of states is how to cope with an accumulation of unfunded public pension and retiree health care liabilities, which total more than $1 trillion nationwide. Other challenges include rising Medicaid costs, volatile tax revenue, and uncertainty about federal funding levels.

- Debt and unfunded retirement costs. States collectively owed more for unfunded pension liabilities ($915 billion) than for public debt ($757 billion) or unfunded retiree health care costs ($577 billion) as of fiscal 2012. In 35 states, unfunded pension benefits were the largest of these long-term obligations—which, if not properly managed, can limit the funds available for other priorities and raise borrowing costs.

- State Medicaid spending. The share of states’ own money spent on Medicaid grew in all but one state—North Dakota—between fiscal 2000 and 2013. States’ increases varied widely, from a fraction of a penny to almost 11 cents per dollar of state-generated revenue, exerting different degrees of budget pressure. Medicaid is most state governments’ second-biggest expense, after K-12 education.

- Tax revenue volatility. Some states experience greater swings in tax revenue from year to year than others do, leading to surprise shortfalls or windfalls that can make it hard to manage budgets. Alaska experienced the greatest volatility over the past two decades and South Dakota the least, after removing the effects of tax policy changes. Taxes on corporate income and oil and mineral extraction were consistently more volatile than other major tax streams.

- Federal share of state revenue. The federal government is the second-biggest source of state revenue—accounting for 30 percent of the total in fiscal 2013—meaning that federal budget decisions also play a key role in state budgets. But states’ reliance on federal funds varies widely, ranging from 19 percent of revenue in North Dakota to almost 43 percent in Mississippi.