How Debt Collection Works in Philadelphia’s Municipal Court

High rates of default judgments underscore need for reform, particularly in service of process

Overview

American household debt has more than tripled since 1999—from $4.6 trillion1 to $15.84 trillion2 in real dollars in 2022. More than three-quarters of families experience some form of debt, and a third of those with consumer credit reports have a debt in collection. Debts are increasingly driven not by loans but by expenses such as out- of-pocket medical fees and unpaid utility and telecommunications bills.3 In 2019, the latest year for which data was available, credit card debt was the most widely held debt, affecting 45% of American households.4

When consumers fail to pay their debts, creditors can file lawsuits to try to collect. In Philadelphia, debt collection lawsuits for dispute amounts of up to $12,000 are filed as small claims cases in Municipal Court. Cases involving greater amounts are adjudicated in the Court of Common Pleas.

Philadelphia Municipal Court data from 2013 to 2018 showed that the majority of the more than 100,000 small claims cases in Philadelphia courts were debt collection cases filed against individuals by creditors or debt collectors. And the median total judgment amount—which includes the total outstanding debt claim, accrued interest, court costs, and other fees—was $2,182.

Individuals sued for debt collection in Philadelphia Municipal Court learn about the case against them through service of process—a legal procedure that begins with attempted hand-delivery of court-mandated forms notifying individuals of a lawsuit against them. Service is a first and critical step in ensuring that defendants are afforded their constitutionally guaranteed right to procedural due process.

Although most cases during the study period were coded in the court’s case management system as successfully served, defendants in those cases did not appear or otherwise respond to the court 59% of the time, resulting in a default judgment being entered against them.

When facing debt collection, people may not engage with the court for various reasons, including a lack of understanding of the process, lack of awareness of the options available to them (such as whether they need an attorney), or feeling overwhelmed by the suit brought against them. But the high rates of defendants’ absence in court—as well as prior research—raise questions and concerns about the viability and adequacy of Philadelphia’s service of process rules and practices.

For example, according to a survey by The Pew Charitable Trusts of small claims defendants who were sued in Municipal Court in 2018, “22% of respondents who did not attend their court hearings said the main reason was that they did not know a lawsuit had been filed or a hearing scheduled.”5

According to Pew’s calculations, of the nearly 45,000 cases during the study period for this report that ended with a judgment—which excludes cases that were settled or dismissed at an earlier stage—95% resulted in a default judgment against the defendant because the defendant did not appear in court. When defendants lose by default, a court commissioner—who oversees initial debt collection hearings unless a defendant requests a trial before a judge—awards the plaintiff all damages sought, even without any response from the defendant either acknowledging or contesting the claims.

Debt collection cases can have devastating consequences for consumers. In addition to accrued interest and late fees, default judgments may include court costs and attorneys’ fees, and can far exceed the original amount owed.6 In many jurisdictions, debt judgments can result in wage garnishments (or bank account garnishments in Philadelphia, where state law prohibits wage garnishment), liens on property, and the inability to secure housing, credit, and employment.7

This report aims to clarify the relationships among service of process in Philadelphia Municipal Court, low participation rates in court among defendants, and case outcomes for individual debt collection defendants. The researchers also analyzed court data focused on rates of successful service and case outcomes from similar courts in two comparison jurisdictions: Chicago and Detroit.

Among the key findings:

- A variety of factors can lead to defendants’ lack of engagement with the Philadelphia court, including faulty service, inaccessible case information for defendants, and personal factors that deter defendants from responding.

- Although Philadelphia Municipal Court has recorded many small claims cases as having been effectively served, survey results and interviews with experts from Community Legal Services, the financial counseling organization Clarifi, and the University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School—along with court personnel, plaintiffs’ attorneys, and process servers whose work regularly involves the Municipal Court—suggest that current service of process rules and practices are not effectively engaging all defendants in their debt collection cases.

- Chicago, Detroit, and Philadelphia are similar in their relatively high reported rates of successful service and low defendant participation with the court, which results in high rates of default judgments against defendants, according to an analysis of court data and conversations with court staff.

- Process servers, courts, and other stakeholders can implement emerging promising practices from a range of jurisdictions that could strengthen service of process rules and practices to complete more successful defendant notifications—and ensure that defendants have the clear and understandable information they need to respond to debt collection lawsuits. Examples include requiring plaintiffs to provide more robust verification of attempted service, serving defendants with clear and understandable information about how to respond to a debt collection lawsuit, and ensuring that affidavits of service are legally sufficient.

These findings align with growing national concern about the legal adequacy and sufficiency of service of process practices. A 2020 National Center for State Courts report raised concerns about the rising number of debt collection cases, citing issues with service of process as well as the need for courts to manage debt collection cases in a more consistent and coherent manner. According to the report, “Over the past decade, courts have become increasingly aware of two distinct case management problems specifically with respect to service of process—one involving inadequate review of the case file and the other involving outright fraud on the court.”8 In the same year, Pew’s review of debt collection in state courts showed that many states’ service of process rules do not include a requirement to verify that the defendant was actually contacted.9

Lack of engagement in court cases is problematic for all parties involved. In the debt collection cases analyzed for this report, the combination of the high volume of cases—most of which are never disputed before a judge— and low defendant participation rates suggests that Philadelphia Municipal Court might want to re-examine the effectiveness of service of process, acknowledge some natural barriers, and implement practices to ensure that defendants have the information they need to respond to debt collection lawsuits.

Inequities in Debt and Collections

Although the negative consequences of debt affect people of all races, ethnicities, ages, and socioeconomic classes, lower-income populations and people of color are hit especially hard and are more likely to experience collection activity. For lower-income populations, debt is nearly impossible to avoid—in 2020, more than 1 in 3 adults in the U.S. said they would be unable to cover a $400 emergency expense10—and it is more likely to be unsecured, meaning that it is not backed by collateral.11 Further, for lower-income populations, debt is disproportionately from credit cards, high-cost unsecured loans, and unpaid bills.12

People of color are disproportionately subject to debt collection, debt collection lawsuits, and the downstream effects of debt collection, even when accounting for income. Several factors have been shown to contribute to this disparity, including a history of discrimination that resulted in families of color having access to fewer financial resources, and systemic debt collection practices that yield a higher volume of lawsuits by debt buyers for smaller dollar amounts than what a typical bank would bring to court.13 Nationally, as of 2021, in ZIP codes where the majority of residents are people of color, 39% have debt in collection, compared with 24% in ZIP codes where the majority of residents are White.14 In Philadelphia, Black defendants are overrepresented in debt collection lawsuits. According to a 2021 Reinvestment Fund report, 49% of debt collection cases in the city involved Black defendants, although only 41% of Philadelphia households identify as Black; and 27% of the cases involved White defendants, though 34% of households identify as White.15

How the court handles debt collection cases

In Philadelphia, small claims lawsuits seeking judgments up to $12,000 are resolved in Philadelphia Municipal Court—the lowest rung of the judicial system and designed to be the most accessible. Attorneys are permitted, but the expectation is that individuals should be able to navigate civil cases without one. From 2013 to 2018, only 12% of defendants had lawyers, compared with 91% of plaintiffs who did.16

In recent years, small claims lawsuits have made up an increasing proportion of the court’s cases. In 2018, Philadelphia Municipal Court heard about 91,000 cases. Small claims cases, which include debt collection lawsuits, accounted for 31% of all litigation, an increase from 23% in 2016.17

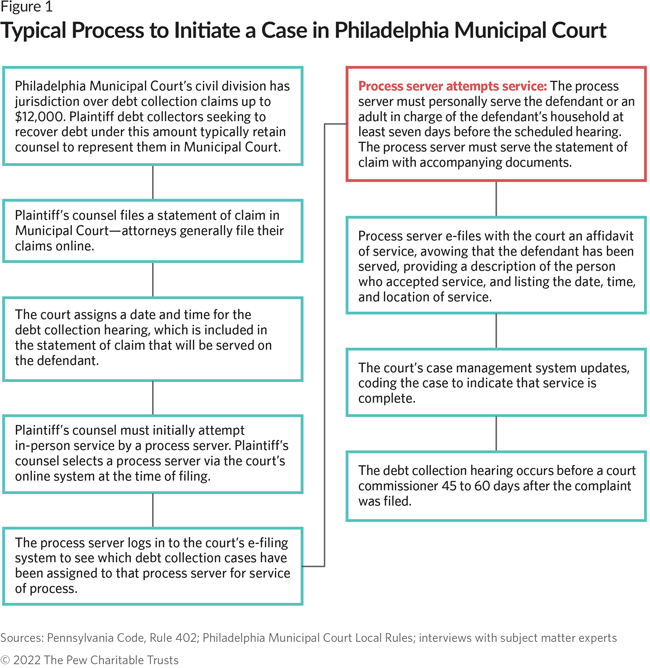

In Philadelphia, a debt collection lawsuit requires a plaintiff, who is a creditor, to file a statement of claim in the court’s First Filing Unit or through the e-filing system, after which a process server delivers the service packet to notify the defendant.18 Most plaintiffs in these cases have legal representation, so the creditor’s attorney typically completes the filing process.19

The steps and procedures in service of process

Service of process in Philadelphia is governed by Pennsylvania Code Rule 402 and Philadelphia Municipal Court’s Local Rule 111. To complete service of process for small claims cases, a process server—acting on the plaintiff’s behalf or through the sheriff’s office—must first attempt to personally serve the defendant with a packet of court- mandated forms at least seven days before the scheduled hearing. If the defendant is not available, any adult in charge of the defendant’s household can receive service.20 After completing in-person service, the process server electronically files with the court an affidavit of service, a form through which the server attests that the defendant has been served, providing a description of the person who accepted service, along with the date, time, and location.

If in-person service of process cannot be completed, plaintiffs are permitted to attempt service by sending the packet via both certified and first-class mail. According to court leadership, in order to serve a defendant in Philadelphia by certified or regular mail, the plaintiff must produce a postal verification or LexisNexis search showing that the address listed is a valid address for the defendant.21 If the documents are not returned as undeliverable and are not returned within 15 days after mailing or by the date of the trial (whichever is later),22 the service is counted as complete.

According to court leadership, staff members in the court’s Second Filing Unit review case materials approximately three days before the hearing to ensure there is proof that the defendant was served, and note whether service has been, in the court’s words, “effectuated, not effectuated, not yet scanned, and/or needs to be reviewed further by courtroom personnel.” The Second Filing Unit provides this information to the courtroom staff members who oversee the hearings to inform how they process each case.

Court records show a case as not successfully served when in-person service was unsuccessful, certified mail does not have a signed return receipt, and first-class mail was returned as undeliverable.23 Court records show that service is marked as complete in approximately 76% of cases; the remaining 24% of cases are dismissed for failure to serve,24 and the plaintiff can choose whether to refile.

Table 1

Documents Included in Small Claims Service Packets

| Statement of claim | Amount owed and date, time, and location of hearing. |

|---|---|

| Notice of language rights | Notice of availability of interpretation services during court proceedings. |

| ADA compliance | Notice of availability of accommodations during court proceedings. |

| Affidavit of nonmilitary service | Written statement confirming that the plaintiff is not serving a defendant on active military duty. |

| Court instructions/FAQ | Document from the Philadelphia Municipal Court regarding a defendant’s rights and responsibilities before, during, and after he or she is sued in small claims court. |

| Notice to defend (optional) | Form that requires the defendant to notify the plaintiff of his or her intent to enter a defense or counterclaim. Plaintiffs are not always required to include this form in the packet. |

Source: The Pew Charitable Trusts, “How Philadelphia Municipal Court’s Civil Division Works” (2021), https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2021/02/how-philadelphia-municipal-courts-civil-division-works

Service During the Pandemic

The Philadelphia Municipal Court closed for several months, between March and July of 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic first prompted lockdowns. According to Bradley Moss, the civil division’s supervising judge at that time, the court issued new rules and procedures to proceed with cases on an emergency basis, but overall, court operations were extremely limited.26 Once the court reopened, service of process practices resumed as before. In interviews, multiple stakeholders noted that COVID-19 presented new challenges to service of process. Defendants became more reluctant to answer the door in light of social distancing requirements, and more residents have implemented remote door monitoring through security systems. For process servers and courts, these processes present challenges in determining whether service has occurred if defendants answer through a security system, indicate that they are home, and request that service packets be left at the door. Under current Philadelphia court guidelines, that would not be sufficient for successful service.

Analyzing types of plaintiffs and case outcomes

In Philadelphia Municipal Court, there are at least 11 types of debt collection plaintiffs, ranging from debt collectors and banks to utilities and insurance companies. During the study period, the largest volume of cases was brought by debt collectors, with at least 26 plaintiffs filing more than 46,000 cases. Banks, credit unions, and other lenders, a category made up of at least 28 plaintiffs, filed more than 25,152 cases during this time. The third highest-volume filer is the city of Philadelphia.

There are several possible outcomes after a case is filed with the court. (See Table 2.)

Table 2

Philadelphia Case Outcomes, 2013-18

| Outcome | Number of cases (117,117) | Percentage of cases |

|---|---|---|

| Judgment for plaintiff by default | 40,711 | 35% |

| No service, dismissed without prejudice | 28,300 | 24% |

| Cases without a final outcome* | 21,623 | 18% |

| Withdrawn without prejudice | 9,648 | 8% |

| Blank or null | 9,236 | 8% |

| Settled, discontinued, or ended | 5,061 | 4% |

| Judgment for plaintiff | 1,277 | 1% |

| Judgment for defendant† | 949 | 1%< |

| Other outcomes‡ | 312 | 0.3% |

Note: Percentages do not add up to 100% due to rounding.

* “Cases without a final outcome” refers to cases that were continued past the end of the data set or that were labeled without a clear conclusion.

† “Judgment for defendant” includes judgment by default for defendant.

‡ “Other outcomes” include withdrawn cases and “satisfied judgments” without a named judgment in favor of one litigant. Source: Philadelphia Municipal Court

Glossary of Terms: Case Outcomes

Judgment for plaintiff by default: The defendant does not appear in court for the hearing, and judgment is automatically entered for the plaintiff.

Withdrawn without prejudice: The plaintiff does not move forward with the case and retains the ability to refile; for instance, if the two parties come to an agreement outside of court.

Settled, discontinued, or ended: The two parties agree to terms and resolve the case in court but without a judgment.

Judgment for plaintiff: The defendant appears in court, and the case is argued before a judge, who rules in the plaintiff’s favor.

Judgment for defendant: The case is argued before a judge, who rules in the defendant’s favor; or the plaintiff does not appear, and the defendant wins by default. No judgment is entered against the defendant, or the defendant filed and won a counterclaim against the plaintiff.

No service, dismissed without prejudice: The process server tasked with notifying the defendant of the lawsuit and the hearing on it reports being unable to do so, and the case is dismissed. The plaintiff has the option to refile the case and try again to serve the defendant.

Outcome unknown: The court data contained insufficient information to determine the case’s outcome.

Source: The Pew Charitable Trusts, “How Philadelphia Municipal Court’s Civil Division Works” (2021)

Debt collection in comparison cities: How Philadelphia stacks up

As part of this research, Pew analyzed available civil case data from two comparison jurisdictions: the 36th District Court in Michigan (“Detroit”) and the State of Illinois Circuit Court of Cook County, 1st Municipal District (“Chicago”).27 Data analysis focused on understanding rates of successful service and overall case outcomes.

Chicago and Detroit were selected as comparison jurisdictions for multiple reasons, including data availability and some shared characteristics with Philadelphia. Chicago was selected for comparison as another city with a large and diverse population, and Detroit was selected as a city with a similarly high poverty rate. Although all act as limited-jurisdiction civil courts, the other two jurisdictions have higher dollar limits on small claims cases—$30,000 in Chicago and $25,000 in Detroit, compared with Philadelphia’s $12,000 maximum. In Chicago between 2013 and 2019, some 190,623 cases were filed and 126,901 were reported as successfully served. And in Detroit between 2014 and 2018, some 234,935 cases were filed and 186,229 were reported as successfully served.

Key findings:

- The majority of debt collection cases filed in Philadelphia, Chicago, and Detroit are coded in the courts’ case management systems as successfully served.

- The largest share of debt collection cases in these jurisdictions result in a default judgment against the defendant.

- In each jurisdiction, eight plaintiffs collectively file at least half of the debt collection cases that are successfully served.

Service of process outcomes in Chicago, Detroit, and Philadelphia

In Chicago and Detroit, service of process can be completed either in person via a process server or sheriff’s office employee, or by certified mail delivery restricted to the defendant. In Chicago, certified mail is limited to cases in which the claim is less than $10,000 and the defendant is physically present in Illinois.28 Additionally, in Detroit, if personal service is not possible, the plaintiff can request an order for alternate service and post service of process at the defendant’s address.

Each jurisdiction codes service of process as successful in its case management system based on similar filing events: In Philadelphia, when the plaintiff files an affidavit of service; and in both Chicago and Detroit, when the plaintiff files a proof of service form. Process servers sign these documents, avowing to the court when, where, and how service of process was attempted and providing a description of who was served.

In Chicago, Detroit, and Philadelphia, the majority of debt collection cases that are filed are coded in the courts’ case management systems as successfully served. Detroit and Philadelphia have similar reported successful service rates, at 79% and 76%, respectively; the rate of successful service in Chicago is slightly lower, at 65%.

In each of these jurisdictions, the majority of debt collection cases that are documented as successfully served end in a default judgment against the defendant—typically for the monetary amount requested by the plaintiff in the complaint, plus court fees. The default judgment rate is higher in Detroit, at 69%, than in Philadelphia and Chicago, at 59% and 53%, respectively.29 (See Table 3.)

Table 3

Case Outcomes When Service of Process Is Reported as Complete in Chicago, Detroit, and Philadelphia

| Jurisdiction | Percentage in which plaintiff received default judgment | Percentage that ended in a dismissal by either party | Percentage in which case was withdrawn or settled | Percentage in which plaintiff received a judgment on the merits | Percentage in which defendant received a judgment on the merits |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chicago | 53%* | 34% | 11% | Unknown† | <1% |

| Detroit | 69% | 21% | 4% | 2% | 3% |

| Philadelphia | 59% | Unknown‡ | 21% | 2% | 1% |

* In the Chicago data set, case outcomes were determined by docket entry analysis. Each unique case has multiple docket entries, and some cases had conflicting or overlapping outcome docket entries. For example, 3,954 of the 190,623 cases in the Chicago data set had no docket entry code indicating that service had occurred but nonetheless had a docket entry code indicating that a default judgment was entered against the plaintiff. Those 3,954 cases have been excluded from this report’s calculation of the number of cases in which service occurred and the case ended in default judgment against the defendant.

† In Chicago, 81,098 (66%) of the 123,382 cases with a docket entry indicating that service had occurred also had a docket entry indicating judgment against the defendant. There is no reliable way to analyze the data set to determine which of those 81,098 cases involved a judgment on the merits versus a default judgment.

‡ In the Philadelphia data set, case outcomes do not track dismissals beyond withdrawn or settled cases. The only case outcomes labeled as dismissals are for no service.

Note: These outcomes represent 123,382 cases in Chicago, 186,229 cases in Detroit, and 88,817 cases in Philadelphia. Sources: Cook County Circuit Court in Illinois; 36th District Court in Michigan; Philadelphia Municipal Court

Philadelphia debt collection: Community perspectives

Defendants and experts offer insight into what may prevent people from engaging with the courts—including current service of process rules and practices.

Although some debt collection cases in Philadelphia are dismissed without prejudice for no service or otherwise settled outside of court, 95% of the cases that reach a judgment end in default judgments against defendants because they do not appear in court. In 2021, Pew released a survey of 308 defendants who were sued in Philadelphia Municipal Court in 2018 for debt collection. The survey aimed to learn more about defendants’ experiences before, during, and after their cases. Sixty percent of defendants reported not attending their court hearing, with 22% indicating that the primary reason for their absence was that they did not know a lawsuit had been filed.30

To better understand the experiences of individuals facing a debt collection case in Municipal Court, Pew conducted in-depth interviews with eight defendants in cases that took place in the past five years, including two who participated in the earlier survey. (We agreed to protect their privacy by withholding their names.) Five of the eight defendants had a default judgment entered against them, but only one reported receiving service of process, which was completed by mail.

Separate interviews with subject matter experts in Philadelphia—including attorneys, process servers, judges, court personnel, community organization representatives, and plaintiffs—suggest that defendants’ failure to participate in their small claims cases rests heavily on service of process rules, practices, and procedures. Major takeaways from the interviews with both groups include:

- External factors in defendants’ lives can complicate successful service of process.

- Despite court records indicating that they had been successfully served, many defendants who were interviewed or surveyed were not aware that they had been sued. Experts attribute this outcome to questionable service methods and practices.

- Experts, especially attorneys, complained about the court’s accepting deficient affidavits of service—for instance, those that include incomplete information or that document a method of service that does not comply with court rules—as proof of successful service. A quantitative review would require an intensive document review of a random sample, which was not conducted in this analysis.

- Defendants did not always understand the case information provided in the service of process forms.

- Defendants who received service or otherwise learned about their cases reported feeling too overwhelmed or powerless to take action.

External factors in defendants’ lives can complicate successful service of process

Nearly 1 in 4 cases filed during our study period were dismissed for no service, indicating that plaintiffs and process servers sometimes face challenges in reaching defendants to notify them about the case against them. In-person service rules are grounded in the assumptions that a defendant’s address will be correct, the defendant will be home at the time of service, and the defendant will accept service willingly. Interviews in Philadelphia suggest that these assumptions are often incorrect. Additionally, some defendants live in apartment complexes that restrict public access to specific residences without a key or code, making it impossible for a process server to issue in-person service.

Subsequent attempts at service by mail can be unsuccessful, for instance, when defendants have moved and the address where service is being attempted is no longer correct.

Despite court records indicating that they had been successfully served, many defendants who were interviewed or surveyed were not aware that they had been sued. Subject matter experts attribute this outcome to questionable service methods and practices.

Pew’s earlier survey of debt collection defendants found that 22% of respondents who did not attend their court hearings said the main reason was that they did not know a lawsuit had been filed or a hearing scheduled. This survey included only individuals whose cases proceeded through the court, so service was reported as complete.31

Additionally, of the eight defendants interviewed for this report, only one reported having received service of process. However, all of these cases moved forward, indicating that the court accepted an affidavit of service and that service was marked as successful; five of the cases ended in a default judgment.

Numerous subject matter experts—including Kim Rogers of the financial counseling organization Clarifi, University of Pennsylvania law professor Louis Rulli, and Community Legal Services attorney Laura Smith, who work with individuals facing debt collection cases in Philadelphia—cited incidents in which process servers’ conduct in the field did not comply with the rules, including sliding paperwork under the door, leaving it outside the residence, serving a minor at the residence, or simply reporting that service was made when it wasn’t, a practice referred to as “sewer service.”

Experts, especially attorneys, complained about the court’s accepting deficient affidavits of service—for instance, those that include incomplete information or that document a method of service that does not comply with court rules—as proof of successful service.

According to interviews with court leadership, current standards require commissioners to ensure service of process in accordance with Civil Division rules before a default judgment is entered. Stakeholders who engage with the court have varying opinions about how verification of affidavits of service works in practice. One process server interviewed said he believes that the judges and court commissioners are screening affidavits of service to confirm that service was adequate, although defendants’ attorneys deny that any such screening occurs.

Kerry Smith, a senior staff attorney at Community Legal Services (CLS), said: “I can’t think of a time I’ve ever seen someone at the court review an affidavit of service and determine it to be facially invalid without the issue first having been raised by an attorney.” Stakeholders reviewing the court’s docket, including CLS attorney Laura Smith and Kim Rogers of Clarifi, cited numerous examples of defective affidavits of service that failed to comply with rule requirements because they included no identifying information about the person who allegedly accepted service, stated that a minor accepted service, and/or stated that the paperwork was left at the door.32 Each of those examples was pulled from cases that eventually ended in a default judgment against the defendant.

One of the defendants who was interviewed for this report learned about her case from a consumer law firm’s solicitation mailing and eventually located the affidavit of service that had been filed in her case by searching the court’s website. It listed the person served as “Jane Doe female,” with no other identifying information. In another matter, Rogers reported that the service affidavit in one of her clients’ cases listed a race and gender for the person served that did not match anyone in the client’s household.

Court leadership said the court has recently initiated training on confirming adherence to service of process rules and procedures before entering a default judgment.33

Defendants did not always understand the case information provided in the service of process forms.

Service of process documents’ primary purpose is to alert defendants about the nature of the lawsuit against them and how to take action.

However, several stakeholders highlighted concerns about the paperwork’s length and complexity. CLS’ Kerry Smith commented that service of process paperwork is “incomprehensible to most of our clients.” As a result, defendants struggle to locate the date and time of their hearing, or to exercise their option to have their case tried by a judge instead of processed by a court commissioner, which would require the plaintiff to present evidence and allow the defendant to put forth a defense. Pew’s prior survey of debt collection defendants found similar challenges among respondents—with 50% agreeing that it was difficult to figure out where to go for their hearing and 56% reporting that it was difficult to understand what they needed to do to defend themselves in court.

Defendants who received service or otherwise learned about their cases reported feeling too overwhelmed or powerless to take action.

Without adequate information and resources to help defendants understand their options for responding to their case, whether they learn about it via service of process or in another way, many can feel unable to take the necessary actions.

Defendants experiencing debt collection are often navigating difficult life events that cause them to incur debt, limit their ability to pay the debt, and diminish their capacity to respond to a debt collection lawsuit. In Pew’s earlier survey, 30% of respondents indicated that a major life event prevented them from paying off the debt. Interviewed defendants similarly described debt incurred when family members were ill or injured, or when unexpected bills hit. One defendant, who was sued for a family member’s debt, said, “It was really weighing on me; I’m grieving for my mother, and I’m trying to resolve this issue that shouldn’t be an issue.”

Some of the eight defendants interviewed knew about their court hearing in advance through sources other than receiving service of process but elected not to attend, noting that they were too scared. This is consistent with findings from Pew’s earlier survey on defendants’ perspectives of what it can be like to navigate the court. Nearly two-thirds of respondents believed that the two sides are not treated equally, most (85%) said you need a lawyer in order to be successful, and less than half said it was easy to understand what was happening in the case.34 As one attorney for defendants put it, “I’ve had plenty of clients who have said to me, ‘You know, I got this notice, I couldn’t deal with it, I put it in the drawer, … I just couldn’t deal with it.’”

Another defendant stated that even when he knew a debt collection judgment had been entered against him, “I don’t have the money to deal with the debt—when I do, I will; but at this point, I’m just trying to survive.”

One defendant, who succeeded in obtaining a withdrawal of the debt collection lawsuit against her on the basis of financial hardship, described weeks of research and preparation that she believes most defendants do not have the ability to pursue: “There needs to be better information out there about how to deal with this, because I think people just see they are being sued, and they know they can’t afford a lawyer or they don’t feel confident in defending themselves. They just don’t know how to even try.”

Promising practices in service of process: How court systems could embrace change

The court has a role to play in ensuring that service of process is effective. Municipal Court Supervising Judge Matthew S. Wolf said that the court recognizes the high default rate in debt collection cases, is aware of the downstream effects of debt collection judgments for defendants, and is seeking ways to mitigate harmful impacts on defendants without compromising plaintiffs’ right to purchase debt and pursue civil lawsuits to collect. He described the court’s efforts to understand and respond to lack of defendant engagement and service of process challenges in Philadelphia Municipal Court, and noted that efforts are underway to reduce the number of default judgments in debt collection cases, particularly purchased debt cases.

Still, judges and attorneys interviewed for this report confirmed that there have been no substantive changes to the rules governing service of process in Philadelphia over the past 15 years. This finding is consistent with the comparison jurisdictions, neither of which has made substantive rule changes in the 15 years preceding the end date of the data sets.

This section describes promising practices that Philadelphia Municipal Court and other courts throughout the country could incorporate to complete more successful defendant notifications, ensure that defendants have the information they need to respond to debt collection lawsuits, and ultimately increase defendants’ participation in these suits.

Completing more successful defendant notifications

In the past few years, increasing attention has been paid to the need to reform the court system, especially given the rise in debt collection cases. For example, in 2020, the National Center for State Courts and the Institute for the Advancement of the American Legal System issued a white paper on debt collection cases outlining a series of reforms and recommendations. According to the report’s authors, “Perhaps the most troubling explanation for defendants’ failure to respond in many cases is that the defendant never received notice that a lawsuit had been filed. Procedural due process mandates that defendants receive meaningful notification when they are named in civil lawsuits.”35

This observation is consistent with Pew’s survey of defendants who had been sued in Philadelphia Municipal Court in 2018, finding that nearly 1 in 4 did not know that a case had been filed against them.36 In New York, California, and Minnesota, state attorneys general have pursued large-scale criminal fraud cases alleging that thousands of defendants were not properly served, resulting in the vacating of tens of thousands of default judgments.37

Courts can consider multiple approaches—including the following three measures—to increase the likelihood that defendants will receive proper notification and that they will understand and be able to respond to the debt collection lawsuits against them.

1. Require creditors to provide defendants with a pre-filing notice of intent to file a debt collection lawsuit.

Some states require that plaintiffs notify defendants of their intent to file a debt collection lawsuit before they are permitted to file the suit.

- North Carolina requires plaintiffs to provide the defendant with written notice of intent to file a claim 30 days before filing. The notice must include the creditor’s contact information, including name, address, and phone number, as well as proof of ownership of the debt; detailed information about the debt, including the original creditor’s name, the original account number, and the contract or other evidence of the debt; and an itemized list of all amounts being sought.38

For these notices to be effective, it is essential that they are written in clear, plain language that the consumer can understand, make clear that a court case has not yet been filed, and provide information about what the consumer must do to take action. If done well, these initial notices give defendants more time to resolve the potential lawsuit outside of court, which could decrease litigation costs and save time and resources for all parties, including the court. These savings could be particularly beneficial in Philadelphia, where, according to recent Pew research, expenditures on judicial and legal services are significantly higher than the average among peer jurisdictions.39

Courts could bolster the impact of such requirements by imposing stopgap measures to ensure that defendants are provided with these pre-filing notices, such as requiring that pre-filing notices be included as exhibits to complaints and screening complaints to ensure compliance with that requirement.

2. Require plaintiffs to provide more robust verification of attempted service.

Courts can increase successful notice by requiring plaintiffs to verify defendants’ addresses before attempting service, using photographs and smart technology to document service attempts, and verifying defendant addresses by sending a supplemental notice from the court.

Philadelphia, like many other jurisdictions,40 does not require plaintiffs to take additional steps to verify defendants’ addresses before or after submitting the affidavit of service. Some jurisdictions are amending or considering amending related rules to increase the likelihood that defendants are notified.

- In Massachusetts, plaintiffs must provide an affidavit showing that the defendant’s address has been verified no more than three months before filing a claim through one of three methods: using the return address on correspondence received from the defendant; presenting certified mail that has previously been signed by the defendant at the address; or sending a letter via first-class mail that is not returned as undeliverable, plus verifying the same address through another commercial and, if available, public record.41

Requiring or incentivizing plaintiffs to support their affidavits of service with evidence such as photographs, videos, and GPS locating services could increase the likelihood that defendants are properly notified and could better equip courts to identify and scrutinize false claims of successful service.

- In New York City, all licensed process servers are required to use smart technology, such as GPS locating services, to record the time, date, and location of service.42

Courts can send supplemental materials to addresses listed in filed affidavits of service to verify that the address is correct.

- In New York, at the time of filing the affidavit of service, the plaintiff must provide the court with a stamped, unsealed envelope from the court’s address to the defendant at the same address where service was made. The court mails the notice to the defendant and “will not enter a default judgment if the Postal Service returns the notice as undeliverable.”43

3. Implement stronger safeguards to identify and address deficient affidavits of service.

Courts can create and implement the use of checklists and screening policies that guide court staff and judges in reviewing affidavits of service for legal sufficiency at the time of filing. This practice can help ensure that debt collection cases move through the court system only if service of process has occurred.

In addition to screening affidavits for legal sufficiency at the time of filing, courts could impose a stopgap measure of screening the case file before entering a default judgment, to ensure that service of process occurred.

Courts could also conduct audits to identify improper service and enforce criminal or civil penalties or actions to disincentivize so-called sewer service. The Federal Trade Commission recommends that all courts conduct audits to better understand the nature and extent of service problems, and to identify problems with individual process servers or creditors engaging in unlawful practices.44

- In “Repairing a Broken System,” a 2010 report examining debt collection litigation and arbitration, the FTC called on state and local jurisdictions to consider adopting, among other measures, randomly conducted audits. It cited examples in New York and Illinois in which audits revealed service of process problems.45

Ensuring that defendants are served with the clear and understandable information they need to respond to a debt collection lawsuit

In Pew’s survey of Philadelphia debt collection defendants, 56% of those who did not attend their hearing reported that they were “unsure what they needed to do to defend their cases.” The National Center for State Courts asserts that this factor contributes to high default rates and is a common reason defendants do not respond. Philadelphia stakeholders are concerned that current service of process paperwork does not provide defendants with the information they need to respond to and defend against the debt collection lawsuit. Courts can take action to empower defendants to better understand this process.

Multiple jurisdictions have implemented or are preparing to implement practices that equip defendants with tools and information regarding how and why to respond to a debt collection complaint.

Courts can require the plaintiff to include original account information, such as the name of the creditor and the amount owed, in the service of process materials. Defendants may not believe that they owe the debt being claimed, especially if they do not recognize the name of the creditor filing the complaint or the amount being sought, which can increase over time and include additional fees.

- In 2011, Maryland began requiring that, when the plaintiff is not the original creditor, pleadings include the name of the original creditor, information about the original debt amount, and proof that the defendant opened the account, to help consumers more easily recognize the debt in question.46

Courts can require that service materials include accessible information that clearly explains how to respond to the claim and where to seek additional resources.

- In Alaska, which has relatively low default rates for debt collection lawsuits,47 plaintiffs must serve defendants with a copy of the answer form and the Alaska Small Claims Handbook.48 The handbook includes step-by-step information on filing an answer, with specific instructions for each required section of the answer form. Additionally, Alaska courts have created a self-help debt collection case website, developed a variety of plain-language forms, solicited feedback from the legal community on the revised forms, and proposed changes to court rules to facilitate participation by litigants without lawyers.49 Alaska Court System Administrative Director Stacey Marz has said that “giving defendants these tools may be responsible” for Alaska’s lower default rate in debt collection cases.50

Conclusion

If the household debt trends of the past two decades continue—especially as Philadelphians navigate the economic fallout of COVID-19 and the pressures of rising inflation—continued scrutiny of debt collection litigation practices is warranted. Current service of process rules and practices in Philadelphia Municipal Court may not effectively notify defendants of the debt collection cases being filed against them, and individuals who do not attend court are highly likely to incur default judgments against them that can cause long-term harm to their economic security and financial well-being.

According to CLS attorney Laura Smith, defendants who do not receive service of process “lose the opportunity to show up and defend themselves, … they lose the opportunity just to even know that they’re being sued, … they lose the chance to seek legal help, [and] they lose the chance to promptly dispute the debt if there are problems.” Defendants also end up with a heightened risk of potentially devastating monetary judgments against them. And those judgments grow the longer they go undiscovered or ignored.

The debt collection issues playing out in Philadelphia align with similar trends in the comparison jurisdictions of Chicago and Detroit, and in other courts throughout the country. State and local government officials can explore and adopt best practices and new innovations in service of process and court procedures as a first step toward advancing a modernized civil legal system that encourages defendants to engage and ensures the due process to which they are entitled.

Endnotes

- Federal Reserve Bank of New York, “Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit” (2010), https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/interactives/householdcredit/data/pdf/DistrictReport_Q22010.pdf.

- Federal Reserve Bank of New York, “Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit,” (2022), https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/interactives/householdcredit/data/pdf/HHDC_2022Q1.

- The Aspen Institute, “Consumer Debt: A Primer” (2018), https://www.aspeninstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/ASPEN_ConsumerDebt_06B.pdf.

- Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, “Federal Reserve Bulletin: Changes in U.S. Family Finances From 2016 to 2019— Evidence From the Survey of Consumer Finances” (2020).

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, “How Philadelphia Municipal Court’s Civil Division Works” (2021), https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2021/02/how-philadelphia-municipal-courts-civil-division-works.

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, “How Debt Collectors Are Transforming the Business of State Courts” (2020), https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2020/05/how-debt-collectors-are-transforming-the-business-of-state-courts.

- L. Presser, “Ambulance, Judge, Jail: When Medical Debt Collectors Decide Who Gets Arrested,” ProPublica, Oct. 16, 2019, https://features.propublica.org/medical-debt/when-medical-debt-collectors-decide-who-gets-arrested-coffeyville-kansas; The Aspen Institute, “Consumer Debt”; The Pew Charitable Trusts, “How Debt Collectors Are Transforming the Business of State Courts.”

- P. Hannaford-Agor and B. Kauffman, “Preventing Whack-a-Mole Management of Consumer Debt Cases: A Proposal for a Coherent and Comprehensive Approach for State Courts” (National Center for State Courts, 2020).

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, “How Debt Collectors Are Transforming the Business of State Courts.”

- Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, “Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2020” (2021), https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/2021-economic-well-being-of-us-households-in-2020-dealing-with-unexpected-expenses.htm.

- The Aspen Institute, “Consumer Debt.”

- Ibid.

- Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, “Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2019: Dealing With Unexpected Expenses” (2020), https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/2020-economic-well-being-of-us-households-in-2019-dealing-with-unexpected-expenses.htm; P. Kiel and A. Waldman, “The Color of Debt: How Collection Suits Squeeze Black Neighborhoods,” ProPublica, Oct. 8, 2015, https://www.propublica.org/article/debt-collection-lawsuits-squeeze-black-neighborhoods; National Consumer Law Center, “Racial Disparities in Consumer Debt Collection” (2019), https://www.nclc.org/images/pdf/debt_collection/fact-sheets/fact-sheet-racial-disparities-in-debt-collection.pdf.

- The Urban Institute, “Debt in America: An Interactive Map,” accessed Nov. 2, 2021, https://apps.urban.org/features/debt-interactive-map/?type=overall&variable=pct_debt_collections.

- E. Dowdall et al., “Debt Collection in Philadelphia” (Reinvestment Fund, 2021), https://www.reinvestment.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/ReinvestmentFund_2021_PHL-Debt-Collection.pdf.

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, “How Philadelphia Municipal Court’s Civil Division Works.”

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- First Judicial District of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia Municipal Court Civil Division Local Rules. Rule 111. Service of Complaints, Non- Execution Process, Petitions and Other Documents, 111 (2018), https://www.courts.phila.gov/pdf/rules/MC-Civil-Division-Compiled-rules.pdf; Pennsylvania Code, Manner of Service, Acceptance of Service, 231 Pa. Code § 402, https://casetext.com/regulation/pennsylvania-code-rules-and-regulations/title-231-rules-of-civil-procedure/part-i-general/chapter-400-service-of-original-process/service-generally/rule-402-manner-of-service-acceptance-of-service.

- M. Wolf and J. Joyce, civil division supervising judge and deputy court administrator for the civil division, Philadelphia Municipal Court, email to The Pew Charitable Trusts, May 2022.

- First Judicial District of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia Municipal Court Civil Division Local Rules. Rule 111. Service of Complaints, Non- Execution Process, Petitions and Other Documents.

- Ibid.

- In a previous report, Pew stated that 32% of Philadelphia Municipal Court cases filed between 2013 and 2018 were dismissed for failure to serve. That percentage was derived from data analysis showing 37,565 of 116,563 cases were coded as “withdrawn for failure to serve.” Analysis conducted from this report concluded that 28,300 of 117,117 cases had a code indicating that service did not occur. Cases that had not yet concluded when the data was pulled were included previously but were eliminated from this analysis.

- First Judicial District of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia Municipal Court Civil Division Local Rules. Rule 114. Notice of Defense. (2018), https://www.courts.phila.gov/pdf/rules/MC-Civil-Division-Compiled-rules.pdf.

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, “How the Philadelphia Municipal Court’s Civil Division Has Responded to the Pandemic” (2020), https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2020/08/13/how-the-philadelphia-municipal-courts-civil-division-has-responded-to-the-pandemic.

- Data set time periods are: Jan. 2, 2013, to Dec. 29, 2018, for Philadelphia; Jan. 2, 2014, to Sept. 30, 2018, for Chicago; and Jan. 1, 2013, to Dec. 31, 2019, for Detroit. Time periods are different due to data availability.

- J. Hunter, clerk, Circuit Court of Cook County, email to The Pew Charitable Trusts, March 15, 2022; Illinois Courts, Supreme Court Rules: Rule 102. Service of Summons and Complaint; Return, 2.102 (2017), https://ilcourtsaudio.blob.core.windows.net/antilles-resources/resources/d890ef39-a2b2-4b43-8014-500f5c3826f3/Rule%20102.pdf.

- The differences in the percentage of cases that are dismissed versus settled in Philadelphia, Chicago, and Detroit may be in part due to differences in how parties report out-of-court resolution to the court. If a plaintiff and a defendant agree on a payment plan out of court, that agreement could include a stipulation by the parties that the case will be dismissed or could result in the case’s being reported to the court as settled/withdrawn by the plaintiff.

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, “How Philadelphia Municipal Court’s Civil Division Works.”

- Ibid.

- Pennsylvania Code, 231 Pa. Code § 402.

- Wolf and Joyce, email.

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, “How Philadelphia Municipal Court’s Civil Division Works.”

- Hannaford-Agor and Kauffman, “Preventing Whack-a-Mole Management of Consumer Debt Cases.”

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, “How Philadelphia Municipal Court’s Civil Division Works.”

- Hannaford-Agor and Kauffman, “Preventing Whack-a-Mole Management of Consumer Debt Cases.”

- J. Leibowitz et al., “Repairing a Broken System: Protecting Consumers in Debt Collection Litigation and Arbitration” (Federal Trade Commission, 2010), https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/reports/federal-trade-commission-bureau-consumer-protection-staff-report-repairing-broken-system-protecting/debtcollectionreport.pdf; North Carolina General Assembly, North Carolina General Statutes Chapter 58: Insurance § 58-70-115, Unfair Practices.

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, “The Cost of Local Government in Philadelphia” (2019), https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2019/03/20/the-cost-of-local-government-in-philadelphia.

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, “How Debt Collectors Are Transforming the Business of State Courts.”

- Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Civil Procedure Rule 8.1: Special Requirements for Certain Consumer Debts (e) Affidavit Regarding Address Verification, Rule 8.1 (e) (Jan 2019).

- J.M. Greacen, “Eighteen Ways Courts Should Use Technology to Better Serve Their Communities” (University of Denver Institute for the Advancement of the American Legal System and Bohemian Foundation, 2018), https://iaals.du.edu/sites/default/files/documents/publications/eighteen_ways_courts_should_use_technology.pdf.

- New York State Unified Court System, § 208.6(h) Additional Mailing of Notice on an Action Arising From a Consumer Credit Transaction,§ 208.6(h) (2018), https://ww2.nycourts.gov/rules/trialcourts/208.shtml#06; The Pew Charitable Trusts, “How Debt Collectors Are Transforming the Business of State Courts.”

- Leibowitz et al., “Repairing a Broken System.”

- Ibid.

- Maryland Court, Rules of Civil Procedure, District Court, 3-306—Judgment on Affidavit, https://casetext.com/rule/maryland-court-rules/title-3-maryland-rules-of-civil-procedure-district-court/chapter-300-pleadings-and-motions/rule-3-306-judgment-on-affidavit.

- National Center for State Courts, “Fair and Efficient Handling of Consumer Debt Actions: Key Steps and Tools to Implement Now” (presentation, webinar, Oct. 20, 2020), https://vimeo.com/476359099.

- Alaska Court System, “Alaska Small Claims Handbook” (2021), https://public.courts.alaska.gov/web/forms/docs/sc-100.pdf; National Center for State Courts, “Fair and Efficient Handling of Consumer Debt Actions.”

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, “How Debt Collectors Are Transforming the Business of State Courts”(2020).

- National Center for State Courts, “Fair and Efficient Handling of Consumer Debt Actions.” Alaska state courts used to take responsibility for managing service and ensuring that defendants receive a copy of the answer form and the Small Claims Handbook. Recently adopted rule changes allow for plaintiffs to take on this responsibility.