Philadelphia's Changing Middle Class: After Decades of Decline, Prospects for Growth

The size of Philadelphia's middle class has essentially stabilized in the past decade after a period of prolonged decline, according to an analysis by the Pew Charitable Trusts of current and past data from the U.S. Census Bureau.

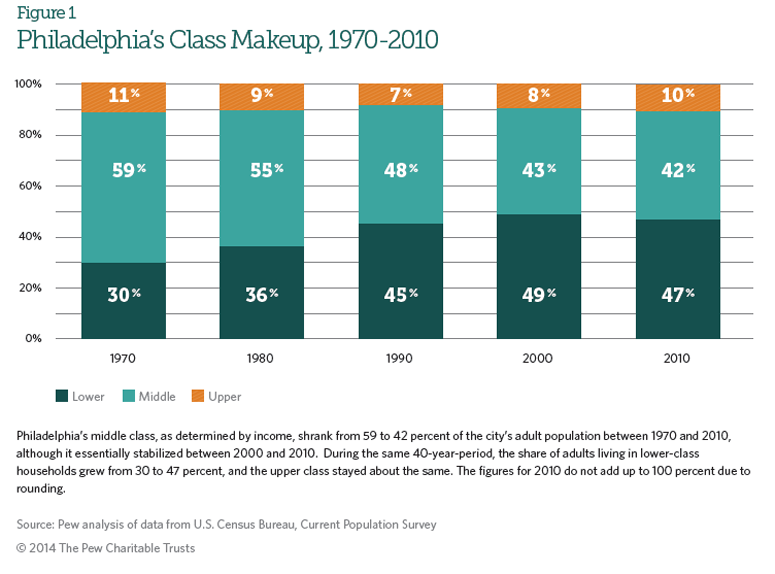

In 2010, 42 percent of the city's adults qualified as members of the middle class, as defined by household income, virtually unchanged from 43 percent in 2000. Both of those figures are down substantially from 1970, when the middle class made up 59 percent of Philadelphia and the city had 400,000 more inhabitants than it does now.

A vibrant and substantial middle class is widely considered essential for economic health and social stability in any community. The challenge for Philadelphia, operating in a climate of budget cutbacks and tax fatigue, is to maintain and grow its middle-class population without shortchanging the needs of lower-income residents. And in Philadelphia, those needs are vast.

The apparent stabilization of the middle class comes after an extended exodus that transformed the city's fundamental economic makeup. Over the past four decades, as Philadelphia's overall population dropped by nearly 22 percent, the city lost more than 4 in 10 of its middle-class adults. At the same time, the lower-income adult population rose by about a quarter and the higher-income adult population fell by about the same percentage.

For the purposes of this report, adult Philadelphians are considered middle class if they are part of a household with an income between 67 and 200 percent of regional median household income. Since the median income was $61,579 in 2010, the range for that year was $41,258 to $123,157.

Today's middle-class Philadelphians are better educated and more likely to work in professional or service jobs than their counterparts of four decades ago and other city residents now.

And they are more racially diverse. In 1970, 74 percent of the adults living in middle-class households were white, 26 percent black. In 2010, the makeup was 54 percent white, 42 percent black, and 4 percent Asian and other groups. In this particular data set from the census, Hispanics are counted as whites, blacks, or members of other racial groups.

Where the middle class lives is different as well. At the beginning of the 1970s, more than 8 in 10 of the city's census tracts, including nearly all of Northeast Philadelphia, were predominantly middle class. By 2010, just over 3 in 10 fit that description, and most of them were clustered in the Northeast, the Northwest, and along City Avenue. Over the course of those 40 years, the average number of people in a middle-class household in Philadelphia has changed from nearly three to less than 2½. The percentage of middle-class adults living alone increased from 19 to 38 percent, and those with children at home dropped from 43 to 33 percent.

The work performed by middle-class Philadelphians has also changed. Gone are many of the manufacturing and midlevel office jobs that vaulted thousands of residents into the middle class. Over the 40 years studied, the share of middle-class Philadelphians employed in finance and other business and professional services increased from 28 percent to more than half, a bigger increase than for residents of the city overall.

In the Philadelphia of several generations ago, one could sustain a middle-class existence without a high school diploma; 44 percent of the middle class did so, and only 8 percent had attended college for four years or attained a degree. Now only 8 percent of middle-class residents lack high school diplomas, while 35 percent have college or graduate degrees.

The size of Philadelphia's middle class is about the same share of the overall city population as in Baltimore, Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles, and New York. What makes Philadelphia different is that it has a higher percentage of lower-income residents than those cities and a lower percentage of higher-income ones.

Middle-class Philadelphians have some distinctive attitudes toward their city. In a poll conducted by Pew in July and August 2013, residents who identified themselves as middle class generally were more satisfied with life in the city than lower-income individuals but less satisfied than people at the higher end of the income scale. They also:

- Gave very low marks to the city's school system and were more supportive than were the other income groups of publicly funded charter schools, which have become a popular alternative to schools that are run by the School District of Philadelphia.

- Disliked taxes intensely. When asked if they generally prefer more services and higher taxes or fewer services and lower taxes, they chose the fewer services/lower taxes option by a larger margin than the other income groups.

- Felt neglected. All three income groups agreed that middle-class Philadelphians get less attention from city government than members of the lower or upper classes. Only 15 percent of middle-class residents said the government caters most to them.

Public officials often say that growing the middle class is a top priority. But with the middle class shrinking nationally and local budgets tight, the options for doing this are limited.

In Philadelphia, policies with appeal to middle-class residents include the 10-year tax abatement on housing construction and renovation, growth of charter schools, and development of amenities such as bicycle lanes and dog parks. Another policy approach is to help lower-income individuals move up the economic ladder through public investments in such areas as career education and workforce development.

According to the Pew poll, the prime concerns of the middle class matched those of most Philadelphians—public safety, job creation, and education—three of the toughest issues facing the city. And the poll suggests that a significant number of middle-class residents will leave if they do not see positive movement on these fronts.