Pew Latin American Fellows Program Marks 30 Years of Research and Community Building

Participants reflect on how the funding has spurred their careers and encouraged discovery

The Pew Latin American Fellows Program in the Biomedical Sciences has supported 300 early-career scientists completing postdoctoral training in the U.S. since its launch in 1991. Intended to strengthen scientific communities across borders, the program helps researchers advance their studies by exchanging knowledge and collaborating with Pew’s community of more than 1,000 biomedical scholars and fellows.

Fellows are also supported with funds to bring their expertise and scientific resources back to their home countries once they complete their training in the U.S.

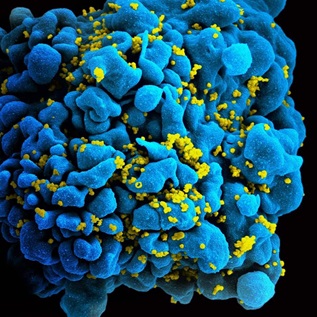

Over the life of the program, promising researchers from 10 countries—Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Guatemala, Mexico, Nicaragua, Peru, Uruguay, and Venezuela—have tackled key questions in health and medicine. Their efforts have spanned a range of subject areas, including microbiology, neuroscience, biophysics, immunology, and genetics, and have contributed to scientific advances across the globe.

During my time as a fellow, I always felt part of something bigger than science—I was a member of a big “familia.” Latin American scientists are underrepresented in the laboratories of top universities in the U.S. It’s hard to find and exchange ideas with people from similar backgrounds. The Pew annual meetings are the exact opposite. There are many aspects that unite us as Latin American scientists, but if I had to define the Pew fellows with one word, that would be “passion.” The passion, the diversity, and the collaborative spirit of the Pew fellows will always endure in the way I approach research, mentor students, and communicate science.

— Cesar L. Cuevas-Velazquez, Ph.D., 2017 fellow associate professor, National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico

The Pew Latin American fellowship allowed me to pursue my research on primate communication in the U.S. I am certain that without the fellowship, I wouldn’t have been able to pursue this pathway. My current research and even my choice of research institute were both a consequence of my training in the U.S. The foundational pieces of equipment for my current research were acquired through the “repatriation” portion of the fellowship. It’s fair to say the Pew community had an enormous influence in shaping my career.

— Daniel Yasumasa Takahashi, M.D., Ph.D., 2010 fellow assistant professor, Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil

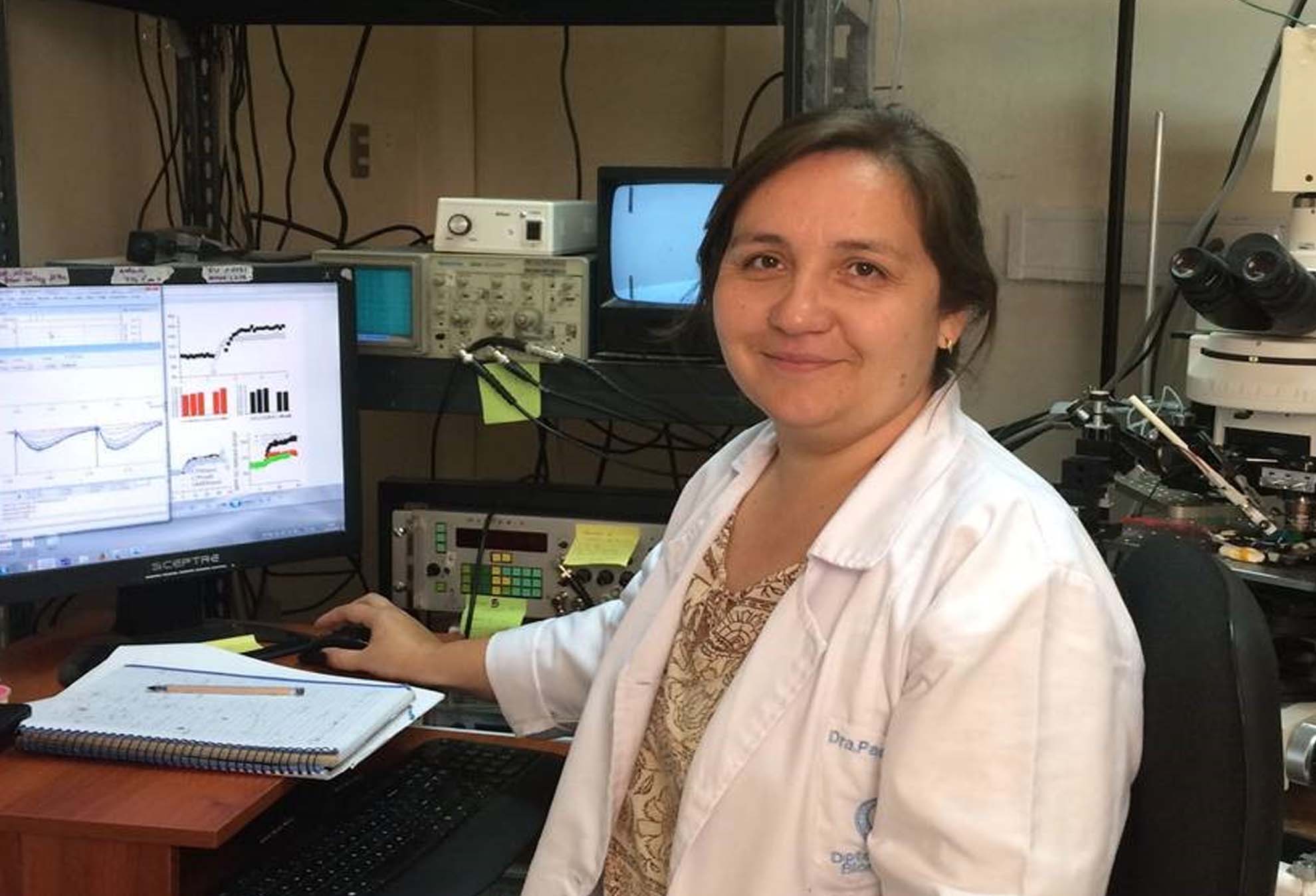

The Pew community has been very important in my career. Being a Pew fellow helped me be more competitive when obtaining a position in Chile and allowed me to quickly set up my own laboratory, thanks to the monetary help for equipment. I appreciate the support among the community as well; fellow scientists are always willing to answer an email and share their knowledge. And the annual meetings were always an opportunity to share experiences and remind me how we should pursue science—by thinking bigger and being rigorous.

— Paola A. Haeger Soto, Ph.D., 2021 Pew Innovation Fund investigator and 2010 fellow associate professor, Catholic University of the North, Chile

Thanks to this program, I was able to study the neuronal physiology of the hippocampal dentate gyrus—a unique neurogenic niche in the adult mammalian brain—which is critical to memory formation. I learned how to perform neural recordings from the dentate gyrus in freely moving animals in one of the best labs in the U.S. when this was not possible in Argentina. This had a great impact when I returned to my country, because not only did I bring back the knowledge of how to do neuronal recordings in this particular brain region, I was able to purchase the first complete Neuralynx recording system in South America with the Pew grant! The Latin American fellow community has helped shape my career. My achievements wouldn’t be possible without it. After returning to Argentina, I’ve continued collaborating with excellent scientists to achieve my scientific goals. It will always be an honor to be part of the Pew Latin American community.

— Verónica C. Piatti, Ph.D., 2010 fellow assistant researcher, National Council of Research

Member, Leloir Foundation Institute—IIBBA, Argentina

It’s very hard to be accepted into top-notch labs in the U.S. when applying for postdoctoral training from Latin America. Having the chance to (partly) support your salary through the Pew Latin American fellows program for at least two years makes you a better fit for hiring. And having the chance to attend meetings and interact with very prestigious people across biology gives you the opportunity to think about your choices—past and future. It makes you a better scientist. Once you’re committed to return to Latin America, having the grant to purchase lab equipment is a game-changer.

— Bruno Manta, Ph.D., 2015 fellow assistant professor, University of the Republic, Uruguay

Senior scientist, Institut Pasteur of Montevideo, Uruguay

As a Pew fellow, I was able to complete my training with support from my university and without losing my teaching position in Ecuador, which was fundamental to avoid brain drain. The funding and support for returning to my country were key factors of the [fellows] program. In that sense, I was in a privileged position because I know of many highly qualified Ecuadorian researchers who were forced to migrate because of the lack of opportunities in local academic institutions. Working in the U.S. opened my perspective to the benefits of technology access and funding in academic institutions. Having the chance to do research in the U.S. and get to know extraordinary people at the Pew meetings was a life-changing experience.

— Sofía Ocaña Mayorga, Ph.D., 2013 fellow investigator, Center for Research on Health in Latin America, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, Ecuador