National Monuments Drive Economic Growth in American West

Land protection boosts local business and job creation, study finds

Proposals to create new national monuments—ranging from vast natural areas to ancestral sites to historic buildings—often spark controversy, especially when large parcels of land are involved. Opponents argue that such protected areas hurt local economies by limiting access to natural resources; supporters counter that monument designations in fact help those communities by attracting tourism- and recreation-driven spending.

A new study bolsters that second stance, finding that creation of national monuments increases the average number of businesses and jobs locally and boosts business and job creation in neighboring areas.

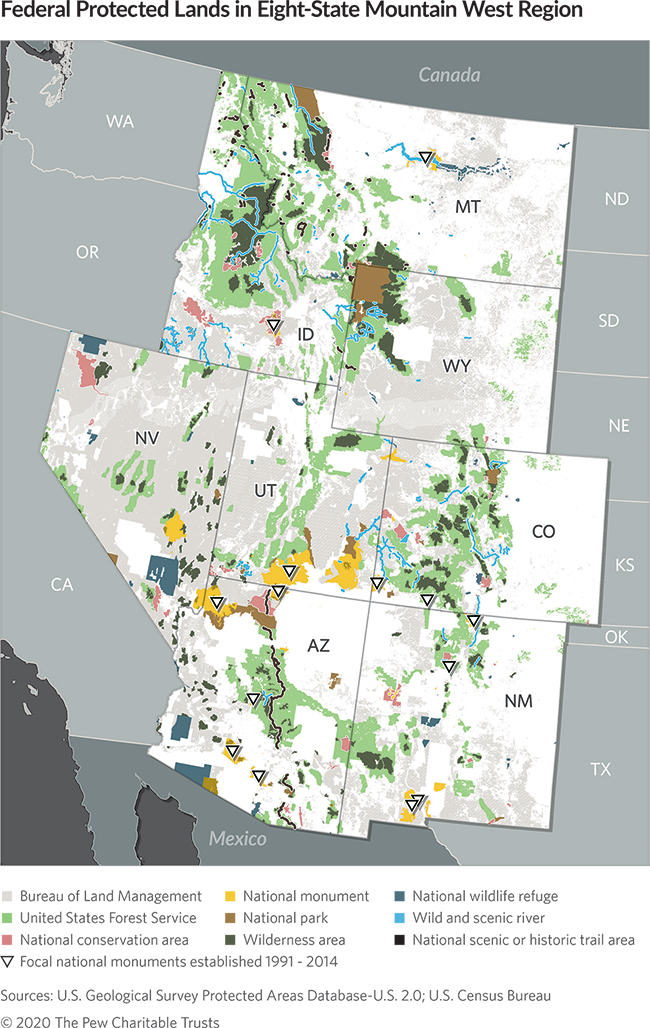

The study, led by Margaret Walls, Ph.D., a senior fellow at the research organization Resources for the Future, investigated the link between monuments and economic impacts over a 25-year period in the American West. The research, published March 18, 2020 in the journal Science Advances, is one of the first to use detailed economic data from the National Establishment Time Series (NETS), a database containing information about every business in the United States. Using NETS, the authors compared the economic effects of monument designation in eight states—Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming—with similar “control” areas that did not gain a monument during the period studied. This comparison allowed the authors to draw a causal link between monument designation and economic impacts.

National monuments deliver healthy returns

The study found that the 14 national monuments established in the American West from 1991 to 2014 helped expand local economies. To assess the effects of monument creation, the study looked at economies from 1990 to 2015 within 15.5 miles (25 kilometers) of a newly designated monument and found that they experienced a 10 percent average increase in the number of businesses established and an 8.5 percent average increase in the number of jobs relative to nearby control locations.

Various service industries—health care, hotels and lodging, business services, and the finance, insurance, and real estate sector—along with the construction industry received the biggest boosts, with average job increases of 16 to 29 percent. The number of businesses and jobs supported by resource extraction industries remained unchanged relative to control locations.

At a regional scale, national monument designations increased the annual net business establishment growth rate by 0.9 percentage points, partially because of a decrease in the rate at which existing establishments closed or relocated. However, there was no increase in the annual net job growth rate. The study found no change in average wages, challenging the perception that monument designations replace high-paying jobs with low-paying ones.

Economic shift in the West

In the past, the economies of Western states relied on public lands for extractive activities such as mining, forestry, grazing, and agriculture. The importance of these activities for the regional economy, however, is declining. Some hope that protecting public lands as national monuments could help counter these declines by creating economic opportunities centered around historic, cultural, and scenic values while preserving wildlife habitat, watersheds, and other ecosystem services.

The remote and unspoiled Vermilion Cliffs National Monument in Arizona is a 294,000-acre geologic treasure. The orange, yellow, and white sandstone swirls make the White Pocket area an outstanding hiking destination.

The United States owns and manages 640 million acres of land, or approximately 28 percent of the country’s total area. More than half of the land in 13 Western states is federally owned. Two federal agencies—the Bureau of Land Management and the U.S. Forest Service—manage the vast majority of those lands and must balance varied and often conflicting uses, including energy production, livestock grazing, recreation, and protection of cultural and historic resources.

National monuments are protected because they contain landmarks, structures, or other objects of significant historic or scientific interest. Although new energy leases are prohibited on monuments, pre-existing leases are allowed to remain, and monument designation often affects livestock allowances only minimally. The new study found that national monuments have no negative effect on these industries after designation.

There is much more that can be learned from the method and data set that the researchers used. Similar studies could be conducted to assess national monument designation in other areas as well as other types of protected sites such as national parks. The researchers recommend further study of social, governance, or other dynamics that contribute to the local economic effects of monument creation—data that could inform proposals for new protected areas.

The Pew Charitable Trusts provided funding to support this research.

Jim Palardy is a project director with The Pew Charitable Trusts’ conservation science program.