How the Cape Town Agreement Can Improve Commercial Fishing Safety

FAQ: International convention would bring fishing industry on par with other maritime sectors, and could help fight illegal fishing

Editor’s note: This fact sheet was updated on June 7, 2022, and again on Sept. 19, 2023 to reflect additional Parties that had ratified the Cape Town Agreement.

Q: What is the Cape Town Agreement?

Adopted by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) in 2012, the Cape Town Agreement for the Safety of Fishing Vessels is an international treaty that aims to protect fishers’ lives at sea from stem to stern by, among other things, establishing standards for vessel construction and related seaworthiness, nonslip decks, heating, ventilation of unmonitored machinery spaces, fire safety regulations, life-saving appliances, emergency procedures and radiocommunications. The Agreement is made up of 10 chapters detailing 176 safety rules.

The Agreement will enter into force once 22 Parties declaring a combined fleet of 3,600 fishing vessels have ratified it; once that happens, fishers would be legally entitled to the same level of protection at sea that is enjoyed by merchant seafarers more than a century after adoption of the first convention protecting seafarers’ lives at sea in 1914.

Scope

Q: To which vessels does the Cape Town Agreement apply?

The Cape Town Agreement primarily applies to fishing vessels that meet all of the following criteria:

- Built after the Agreement enters into force.

- 24 metres or more in length.

- Capable of operating on the high seas.

It does not apply to vessels used for recreation, research or training. Fish carriers and vessels used for processing are already covered by other IMO safety standards and the provisions of the Standards of Training, Certification and Watchkeeping for Seafarers Convention.

Q: Are existing vessels completely excluded from the scope of the Cape Town Agreement?

No, but only five of the 10 chapters of the Agreement apply to existing fishing vessels that are at least 24 metres long:

- Chapter I on General Provisions.

- Chapter VII on Life-Saving Appliances.

- Chapter VIII on Emergency Procedures.

- Chapter IX on Radiocommunications.

- Chapter X on Shipborne Navigational Equipment.

Q: Do all provisions apply equally to all fishing vessels of 24 metres or more in length?

No. The following provisions apply only to vessels that are at least 45 metres long:

- Chapter IV on Machinery.

- Chapter V on Fire Safety.

- Chapter VII on Life-Saving Appliances.

- Chapter IX on Radiocommunications.

Q: Do all provisions apply equally to all new and existing fishing vessels that are at least 24 metres long?

No. The following provisions apply only to new and existing vessels that are at least 45 metres long:

- Chapter VII on Life-Saving Appliances.

- Chapter IX on Radiocommunications.

The following provisions apply only to new vessels of at least 45 metres long:

- Chapter IV on Machinery.

- Chapter V on Fire Safety.

Q: Is the length of a fishing vessel the only way to determine its eligibility under the Cape Town Agreement?

No. Gross tonnage (GT) can also be used by the vessel’s country of registration—also called its flag State. The equivalences are as follows:

- At least 24 metres long = at least 300 GT.

- At least 45 metres long = at least 950 GT.

Entry into force

Q: When will the Cape Town Agreement enter into force?

The Cape Town Agreement will enter into force one year after 22 States have ratified it, as long as they are declaring a combined fleet of at least 3,600 fishing vessels, each of which is at least 24 metres long. A ratification is not official until the Party formally informs the IMO through an official letter expressing its consent to be bound by the Agreement. Such notices are called instruments of ratification.

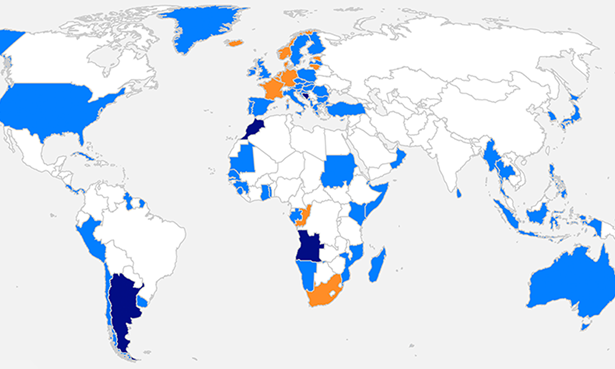

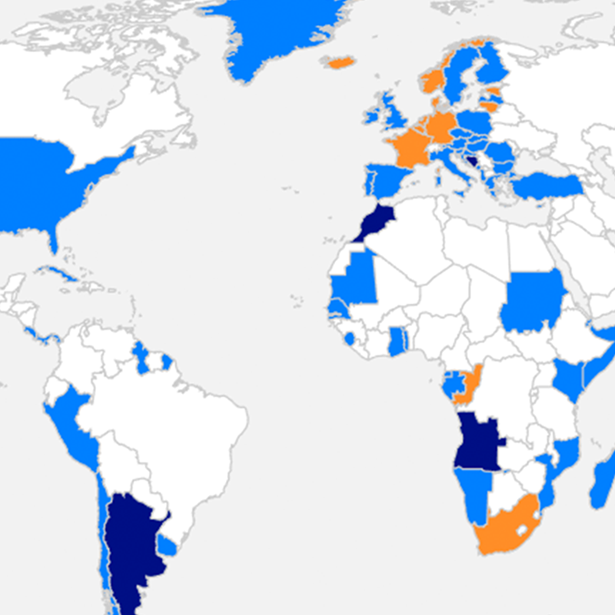

Q: How many States have ratified the Cape Town Agreement?

To date, 21 States, with a combined fleet of 2,603 fishing vessels, have ratified. In October 2019, at the IMO Torremolinos Ministerial Conference on Fishing Vessel Safety and Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated (IUU) Fishing, 48 States signed the Torremolinos Declaration to express their commitment to ratify the Agreement by October 2022, the 10th anniversary of its adoption by the IMO. Three more States signed the declaration in 2020. If the Agreement is fully ratified by October, it could enter into force as early as October 2023.

Q: Will all chapters of the Cape Town Agreement enter into force at the same time?

They could, but if needed, the Agreement provides some flexibility for the application of the following provisions to give States the time to adapt to these new requirements considering the technical adjustments involved on existing vessels:

- Chapter VII on Life-Saving Appliances: up to 5 years after entry into force.

- Chapter VIII on Emergency Procedures: up to 5 years after entry into force.

- Chapter IX on Radiocommunications: up to 10 years after entry into force.

- Chapter X on Shipborne Navigational Equipment: up to 5 years after entry into force.

Should a State decide to use this possibility, it has to justify why and detail its plan for progressive implementation to the IMO when ratifying.

Q: Why do States have to declare a number of vessels when ratifying the Cape Town Agreement?

The declaration of fishing vessels of 24 metres in length and over is purely an administrative formality for the sake of the entry into force of the Agreement. The vessel threshold for entry into force is in place to ensure adequate representation from fishing nations in the Agreement. Flag States are invited to declare fishing vessels from 100 GT in that respect. States can contact the IMO to obtain guidance on the calculation and declaration of their number of vessels.

Q: Are States able to exempt vessels from the requirements of the Cape Town Agreement?

Yes. Flag States may exempt any vessel from any of the requirements of the Agreement, provided that the vessel is not operating on the high seas or leaving national waters.

Phased Implementation of Cape Town Agreement Provisions— Summary

| Chapter | Application1 | Exemption option | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New vessels2 | Existing vessels | |||||

| 24-45 m or 300-950 GT | ≥45 m or ≥950 GT | 24-45 m or 300-950 GT | ≥45m or ≥950GT | Time to implement measures on existing vessels | ||

| I. General provisions | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Upon entry into force | ✓ |

| II. Construction | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | Upon entry into force | ✓ |

| III. Stability | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | Upon entry into force | ✓ |

| IV. Machinery | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | Upon entry into force | ✓ |

| V. Fire safety | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | Upon entry into force | ✓ |

| VI. Crew protection | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | Upon entry into force | ✓ |

| VII. Life-saving appliances | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | Up to five years after entry into force | ✓ |

| VIII. Emergency procedures | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Up to five years after entry into force | ✓ |

| IX. Radio- communications | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | Up to 10 years after entry into force | ✓ |

| X. Shipborne Navigational Equipment | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Up to five years after entry into force | ✓ |

Who should ratify

Q: Why should countries with no coastline or fishing fleet ratify the Cape Town Agreement?

The Agreement is relevant anywhere fish and seafood products are consumed, which means everywhere in the world. Besides, consumers are increasingly demanding that the seafood they buy to be sustainably caught, and 83% of consumers who responded to the GlobeScan survey4 said they are ready to take action to safeguard the oceans. In the survey, which involved more than 20,000 consumers from 23 countries, 65% of respondents said that buying fish and seafood from sustainable sources is “vital,” and 58% said they had already made changes in their consumption choices in the past year to protect fish and other marine life. By ratifying the Cape Town Agreement, States will make it clear that they want fish and seafood that was caught only in a safe and sustainable way to enter their markets.

Q: How could the Cape Town Agreement benefit States near the Arctic and the Antarctic?

States in the Arctic and the Antarctic have comparatively large fishing areas in inhospitable waters, which are potentially expanding due to melting ice caps. The Cape Town Agreement would ensure that fishing vessels in those regions are safer and better equipped, which should translate to fewer accidents, fatalities, distress calls, and search and rescue operations. Vessels that meet the Agreement’s standards would also be better able to assist other vessels in distress, further improving safety at sea for all.

Endnotes

- The Flag Administration may decide to use gross tonnage (GT) in place of vessel length (L) as the basis for measurements for all chapters.

- A new vessel is a vessel built after the entry into force of the Cape Town Agreement.

- The only requirements of Chapter VII that apply to existing vessels concern handheld very high frequency radio and radar transponders.

- GlobeScan, “Concern for the Oceans Drives Consumers to ‘Vote With Their Forks’ for Sustainable Seafood” (blog), June 8, 2020, https://globescan.com/2020/06/08/msc-consumers-vote-with-their-forks-sustainable-seafood/.