Don't Take the Bait!

Myths have persisted for years about the impact of recreational fishing on ocean fish populations and how to manage that impact. Most recently, these myths have resurfaced as justification for a new bill, S. 1916/H.R. 2304, the Fishery Science Improvement Act. Don't let these myths disguise the fact that this legislation would put some of America's most valuable and vulnerable ocean fish populations at risk of overfishing by exempting them from science-based catch limits and accountability measures.

Congress should reject S. 1916/H.R. 2304 and stand strong for the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act.

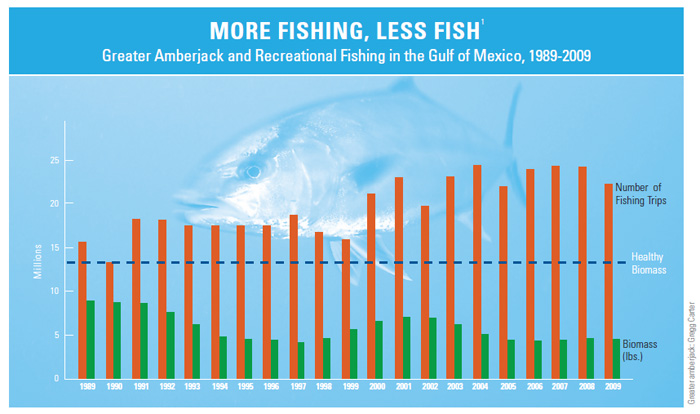

It is hard for some people to imagine that recreational fishing can have much of an effect on the health of ocean fish populations, particularly compared with the impact of commercial fishing vessels, which can bring in many thousands of pounds of fish per trip. In reality, however, millions of individual anglers catching a few fish per trip can have a huge impact on their target fish species.

In 1989, when the U.S. population was 247 million and only birds tweeted, anglers took 15.7 million fishing trips in the Gulf of Mexico. Twenty years later, in 2009, when the U.S. population was 307 million and satellite navigation and sophisticated finders became widely available, anglers took 22.3 million fishing trips in the Gulf of Mexico, a 42 percent increase. The number of individual anglers in the Gulf has also risen, by 64 percent in the past two decades. This increase is understandable—the U.S. population is growing and fishing is fun—but it has serious implications for the health of the region's most popular sport fish. For example, from 1989 to 2009, recreational fishermen took approximately 62 percent of the total catch of greater amberjack. By 2009, the greater amberjack population was depleted to 34 percent of a healthy level because of decades of overfishing.

Historically, recreational fishing has been managed by "bag" limits—restricting the number of fish individual anglers can keep from a trip—or vessel trip limits, not by constraining the total amount of fish killed. Therefore, if the number of fishing trips or anglers goes beyond anticipated levels, the number of fish killed can far exceed the target catch level, leading to overfishing.

Science-based annual catch limits (ACLs), in tandem with accountability measures if the ACLs are exceeded, guard against overfishing by providing an overall cap on catch. Managers use other tools that are tailored to the specific needs and management goals of the fisheries to meet the ACLs. In the Southeast, managers are using ACLs in combination with measures such as bag limits and spawning season closures to manage many species, including black sea bass, gag grouper, red grouper, red snapper, snowy grouper, tilefish, and vermilion snapper.

Information such as average catch and/or biological data exists for every federally managed fish population, including those lacking full assessments. When stock assessments aren't available, scientists and managers rely on these other sources of information to determine sustainable catch levels, including:

- Basic biological information such as growth rates, age at maturity, and reproductive potential, which are used to determine a species' susceptibility to overfishing.

- Average catch data and historical catch trends, which, for example, can indicate future problems if catch is declining.

- Local knowledge and information about catch levels and biology for similar species.

On the West Coast, fisheries managers are using these approaches to determine ACLs for the valuable Pacific groundfish fishery, where less than a third of groundfish have assessments. In the Southeast, managers have set limits at or near current catch levels for some data-limited species with stable levels of catch, such as cobia and wahoo. The National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) is providing additional guidance to managers on models and tools for setting catch limits for fish species lacking full assessments.

Federal funding for fisheries science has increased significantly since the MSA reauthorization in 2006, when Congress mandated science-based ACLs to prevent overfishing.

- Funding for stock assessments, which guide the setting of catch limits by providing scientific analyses of the health of fish populations and the amount of fishing they can support, has more than doubled, from $24.5 million in 2006 to $51.0 million appropriated in 2010.

- Funding for fisheries statistics programs, which include the collection of recreational fishing data, has nearly doubled, from $12.6 million in 2006 to $21.1 million in 2010.

- Funding for survey and monitoring projects, which provide timely analysis of catch and fishing effort, has increased by 63 percent, from $14.6 million in 2006 to $23.8 million in 2010.

In the Southeast, NMFS commissioned the research ship Pisces and dedicated a new lab in Mississippi to support fisheries research in the Southeast and the Caribbean in 2009 and added six stock assessment scientists to the Southeast Fisheries Science Center in 2010.9 Taking away the legal requirement to set catch limits on key species in the Southeast could jeopardize these gains, because NMFS might redirect resources toward regions where the catch limit requirement remains.

After decades of mismanagement that resulted in plummeting fish populations and lost livelihoods, Congress acted in 2006 to strengthen the MSA by requiring an end to overfishing. Although the skeptics had their doubts, we are nearing the finish line, and soon overfishing should be a thing of the past. Congress should reject S. 1916/H.R. 2304 because it would undermine this national success story. Instead, it should support real efforts to improve fisheries science by investing in research, data collection, and monitoring programs of the National Marine Fisheries Service.

To see citations, please download the complete fact sheet.