The Fiscal Cliff and Unemployment Insurance Benefits

Implications for the States

Introduction

Federal policy makers continue to debate the various tax and spending components of the fiscal cliff. Pew's recent report, "The Impact of the Fiscal Cliff on the States", examined the direct impacts many of the scheduled tax and spending changes would have on state budgets. One of the provisions that make up the fiscal cliff is the expiration of certain unemployment insurance (UI) benefits and funding at the end of 2012. Although expiration of these benefits and funding would have little direct effect on state budgets, it could have an indirect impact by affecting economic activity in the states.

The Unemployment Insurance System

Unemployment insurance benefits provide income support to qualifying workers who have lost their jobs for reasons other than poor performance or misconduct. The UI system is jointly funded in part by state payroll taxes and federal taxes and currently comprises three primary programs:

- Unemployment Compensation (UC)—The standard mechanism for providing unemployment compensation is the federal-state UC program, which provides benefits for a maximum of 26 weeks in most states.[i] Dedicated state taxes, levied on employers, pay for most of these benefits.

- Extended Benefits (EB)—Individuals in states meeting certain unemployment rate "triggers" may qualify for up to 20 additional weeks of benefits under the Extended Benefits program. Under permanent law, states pay for half of this program with unemployment insurance taxes, and the federal government covers the other half using revenue from federal unemployment taxes.[ii] The 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, however, temporarily required the federal government to pay 100 percent of EB costs.[iii] The 2012 Middle Class Tax Relief and Job Creation Act (enacted in February 2012) extended this full federal funding through the end of 2012 (with a phase-out).[iv] Currently, no state meets the program triggers.[v]

- Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC)—This temporary federal program was created in 2008 to provide unemployment benefits funded entirely by the federal government for individuals who exhaust their regular state unemployment compensation.[vi] Unlike the Extended Benefits program, EUC applies to all states regardless of their unemployment rates, although longer benefit durations are available in states with higher unemployment rates.[vii] This program has been expanded and extended several times since 2008, providing up to 53 weeks of benefits at one point.[viii] Most recently, the Middle Class Tax Relief and Job Creation Act of 2012 extended the program through the beginning of January 2013.[ix] Currently, EUC provides a maximum of 47 weeks of benefits.[x]

Unemployment Insurance Benefits

Unemployment Insurance and the Sequester

The fiscal cliff also includes across-the-board spending cuts—the sequester—required under the 2011 Budget Control Act and scheduled to take effect in January 2013. Under the sequester, federal unemployment insurance administrative grants to the states would be subject to automatic cuts.vi In fiscal year 2012, these administrative grants accounted for approximately 6 percent of total UI spending.vii States either would have to replace the loss in federal revenues with other resources or implement budget cuts. The federal share of the permanently authorized Extended Benefits program also would be subject to the sequester.

No state currently meets the EB triggers. If a state were to trigger onto the program in 2013, it could, depending on state law, reduce its portion of the benefit amount up to the same percentage as the federal cut. Additionally, if authorization for the temporary Emergency Unemployment Compensation program were extended in 2013, those federal payments also would be subject to sequestration, absent legislative action exempting such benefits. Regular Unemployment Compensation benefits are statutorily exempted from the sequester.viii

As of mid-November 2012, 2.9 million workers—or 24 percent of the total unemployed—received regular state-funded unemployment benefits, and an additional 2 million workers—or 17 percent of the total unemployed—received 100 percent federally funded UI benefits. Of these 2 million workers, 98 percent received Emergency Unemployment Compensation, while about 2 percent (37,000 individuals) received Extended Benefits.[i] (As noted above, currently, no state meets the EB triggers. The small number of program beneficiaries in November comes mainly from New York, which was the only state that was triggered onto the program for that month. It also includes some unemployed individuals in other states that allow claimants to backdate claims.)

The availability of unemployment benefits financed entirely by the federal government has been phasing out during 2012.[ii] Under current law, by the beginning of 2013, Emergency Unemployment Compensation is scheduled to expire completely, and the Extended Benefits program would revert back to its permanent status of being funded equally by the federal and state governments.[iii] According to the Congressional Budget Office, total UI spending is projected to decrease by $34 billion, from $94 billion in fiscal year 2012 to $60 billion in fiscal year 2013,[iv] mostly attributable to the expiration of the EUC program.[v]

Unemployment Facts and Figures

A Year or More

Like the six-month long-term unemployment rate, the percentage of the unemployed who have been jobless for at least a year also remains well above pre-recession levels. For example, in the third quarter of 2012, over 28 percent of the unemployed had been jobless for a year or more.iv That translates to 3.6 million workers.

Even as entirely federally financed unemployment benefits phase out completely, demand is likely to remain high. The unemployment rate in November 2012 stood at 7.7 percent, with a total of 12.0 million jobless U.S. workers.[i] Measured against the 3.7 million job openings in that period, [ii] this translates to more than three unemployed workers for every job opening. The Congressional Budget Office has projected that under current law—which includes all scheduled tax increases and spending cuts under the fiscal cliff—overall unemployment would rise above 9 percent by the end of calendar year 2013 and would not return to the “natural” rate of around 5.5 percent until calendar year 2018.[iii]

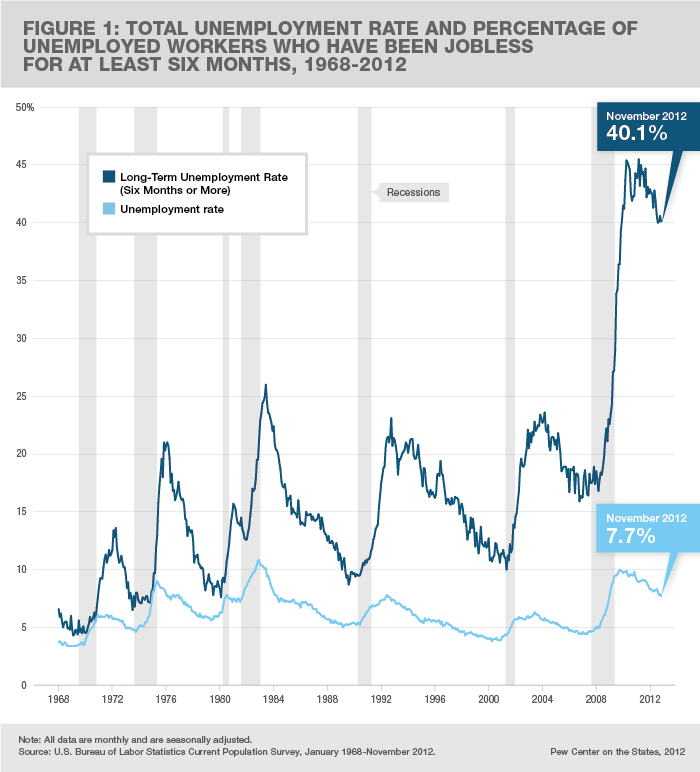

Moreover, in November 2012, 40.1 percent of the total unemployed had been out of work for six months or more[iv]—the limit for state funded Unemployment Compensation benefits in most states. That translates to 4.8 million workers. While the long-term unemployment rate has fallen from its March 2011 peak of 45.5 percent, it remains well above pre-recession levels (see Figure 1). With the scheduled expiration of the EUC program in particular, some longer-term unemployed individuals would lose access to this source of income support.

State Impacts Would Vary

Unemployment rates vary significantly across states. In September 2012, for example, the most recent month for which final data are available, Nevada had the highest unemployment rate—12 percent—while North Dakota had the lowest—3 percent.[i] States' long-term unemployment rates also vary. For example, in 2011, the latest period for which data are available, Florida had the highest percentage of unemployed individuals who had been jobless for at least six months—53 percent—while North Dakota had the lowest rate—14 percent.[ii]

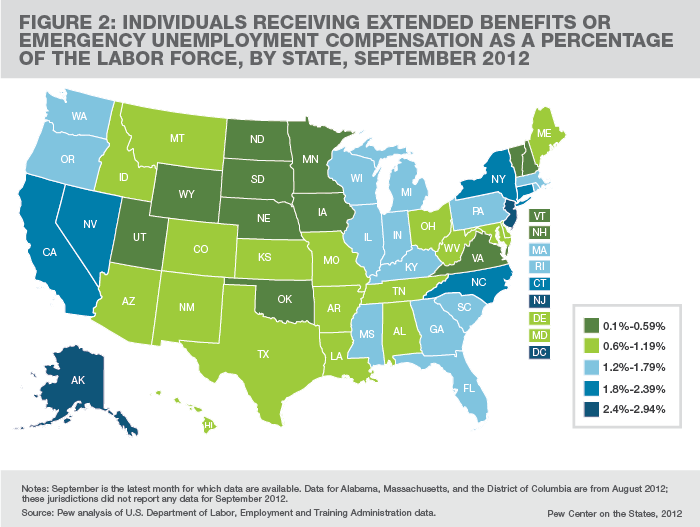

The percentage of the workforce receiving Extended Benefits or Emergency Unemployment Compensation within each state also varies widely. In New Jersey, for example, almost 3 percent of the workforce received federally funded benefits in October 2012 (see Figure 2).[iii] By comparison, the figure was less than 0.1 percent in South Dakota.[iv]

There is disagreement about the impact of unemployment insurance on employment and economic activity. Consequently, it is difficult to determine how state economies—and thus budgets—might be affected by the scheduled expiration of federally funded benefits. In general, however, states with relatively high rates of workers currently receiving such payments would likely experience the greatest impact from the change. Since recipients of Emergency Unemployment Compensation account for 98 percent of all beneficiaries of federally financed unemployment benefits, any state impact would stem primarily from the expiration of this program. Since the Extended Benefits recipients account for just 2 percent of all beneficiaries of federally financed unemployment benefits, any potential state budget impact from the program's scheduled return to equal federal and state funding is likely to be relatively small.

Federal decisions about the fiscal cliff's tax and spending provisions—including whether to allow Emergency Unemployment Compensation to expire and the Extended Benefits program to revert back to its equal federal and state funding status as scheduled—will have consequences for the states. These potential impacts should be considered as federal policy makers evaluate all the costs and benefits of proposals to address the fiscal cliff so that solutions lead to long-term fiscal stability at all levels of government.