Enhancing FDA's Evaluation of Science to Ensure Chemicals Added to Human Food Are Safe (Pre-Workshop Materials)

Pre-Workshop Materials

QUICK SUMMARY

The workshop, co-sponsored by Nature journal, the Institute of Food Technologists (IFT), and the Pew Heath Group, brought together more than 80 scientists and policymakers to develop a shared understanding of the current system FDA uses to assess the hazards of chemicals added to human food and explore opportunities to strengthen that system.

Click here to download FDA Supplemental Materials from the workshop.

Workshop Overview

The primary objective for this workshop is to gather insight and guidance from national and international thought leaders on the best methods to enhance the Food and Drug Administration's (FDA's) evaluation of science to ensure that chemicals added to human food are safe. While the goal is not to reach consensus, identifying and evaluating potential ideas to enhance the development and review of the scientific basis of FDA's assessment of chemicals added, directly or indirectly, to food are priorities.

Over the past 50 years, FDA has developed a complex regulatory program to ensure the safety of chemicals added to food based on the Food Additives Amendment of 1958. This law and later amendments established a number of categories of additives with specific requirements for each. FDA must give premarket approval for all chemical uses defined as food additives (including food contact substances which are food additives), color additives and animal drugs. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) must do the same for pesticide residues. Certain chemical uses expressly approved by FDA or the U.S. Department of Agriculture before 1958 were grandfathered as “prior-sanctioned substances.” There are two remaining categories that do not require agency premarket approval: dietary supplements and uses of chemicals (other than pesticides, color additives or animal drugs) determined by the food manufacturer to be “generally recognized as safe” or “GRAS.”

For food additives, food contact substances, color additives and GRAS substances, safety means that there is reasonable certainty in the minds of competent scientists that the chemical is not harmful under the intended conditions of use. A determination that a chemical is GRAS may be based on either scientific procedures or the common use in food prior to 1958. While an expert panel is not required, there must be evidence that the GRAS substance's safety is common knowledge throughout the scientific community who know about the safety of chemicals directly or indirectly added to food. If using scientific procedures, the determination must be based only on published studies, though they may be corroborated by unpublished studies and other information. If a food manufacturer wants to rely only on unpublished studies, the chemical use cannot be GRAS. To rely on unpublished data, the firm must submit a food additive petition or food contact notification to FDA and secure the agency's premarket approval.

Since food manufacturers can add GRAS substances to food without notifying FDA of their determination, FDA developed regulations to control the basis of these decisions defining the scientific procedures that firms must follow. It also created a program to encourage food manufacturers to voluntarily notify FDA of their determinations.

The result is a regulatory program where scientific decisions on safety are made by FDA or food manufacturers, or both depending on the situation. It also provides an incentive for scientific studies to be published, because food manufacturers can more quickly get a product on the market if a chemical's use directly in food is GRAS.

As the regulatory program developed, toxicology grew into a large and sophisticated field of science to assess the impact of chemicals on human health. In response to concerns about significant problems at private contract testing facilities and to improve transparency and reproducibility of results, FDA adopted a Good Laboratory Practices (GLP) rule in 1978 setting rigorous standards for the documentation and management of animal studies for use in regulatory decision making. To provide some structure and standardization to the assessment, FDA publishes its “Toxicological Principles for the Safety Assessment of Food Ingredients” guidance, commonly known as the “Redbook” (not to be confused with other Redbooks such as the National Research Council of the National Academies' Redbook on risk assessment published in 1983).

In the Redbook, FDA essentially established the current system to conduct safety assessments to

- determine the need for toxicity studies

- design, conduct and report the results of toxicity studies

- conduct statistical analysis of data

- review the histological data

- submit information to FDA as part of its safety assessment of food ingredients.

In the past few years, a controversy emerged during scientific discussions regarding the safety of bisphenol A as a food contact substance in polycarbonate containers and as part of epoxy linings in metal food containers. Several academic researchers maintained that endocrine disruption studies provided sufficient evidence for FDA to determine that there is no longer a reasonable certainty in the minds of competent scientists that the substance is not harmful – the standard of safety required for both food additives and GRAS substances. These scientists believed FDA favored good laboratory practice (GLP) studies using standardized protocols consistent with the Redbook over peer-reviewed studies using the latest methodologies and science published in respected journals by academics. Industry representatives defended the system explaining the need for quality assurance, transparency and reproducibility, and raising questions about the limitations of peer review. An editorial published in Nature called for regulators to take into account new methods as rapidly as they can be validated. The journal published on-line a response by two FDA food additive scientists who explained the role of GLP in improving study reliability, that safety regulation depends on a scientific consensus, and the importance of study design and considering dose and exposure in assessing and managing risk. In addition, they stated their view that experimental—particularly academic—laboratories often lack the financial and physical resources to perform experiments needed to support regulatory decision making on safety.

Against this backdrop, the Pew Health Group decided to convene this workshop to foster a common understanding of the system for determining the safety of chemicals added to food, address emerging

issues and identify opportunities to enhance it. The Institute of Food Technologists—the nation's professional association for food experts—and the Nature journal agreed to cosponsor the event. FDA and NIEHS provided essential planning support.

While the workshop will deal with all aspects of safety assessment, this event will focus on the evaluation of potential human health hazards posed by chemicals added directly or indirectly to human food. A later workshop will focus in more detail on exposure assessment—the other half of a risk assessment. While important to any decision, to help make the discussions more productive we narrowed the workshop's focus to exclude

- pet food or animal feed

- animal drugs

- pesticide residues

- contaminants

- environmental impacts.

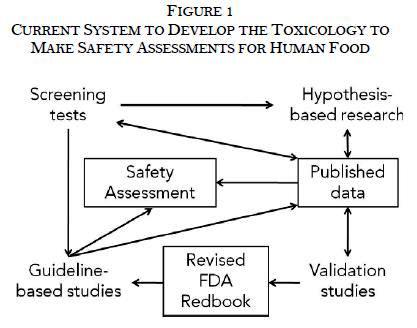

The Pew Health Group developed a framework, described below and in Figure 1, to explain the current system FDA uses to develop the toxicological studies needed to determine whether food additives are safe. Like all frameworks, it simplifies the process and leaves out various nuances.

|

In general, there are four types of toxicological studies represented by the four corners of Figure 1. Each type serves a distinct role in the system: 1. Screening tests identify potential human health hazards from chemicals. 2. Hypothesis-based research explores whether potential human health hazards exist and determines their significance. 3. Validation studies take the methods and protocols from hypothesis-based research to evaluate whether they reproducibly measure adverse effects with an array of chemicals so they can be incorporated into test guidelines such as the Redbook. 4. Guideline-based studies use validated protocols described in the Redbook to assess the hazards in a standardized manner. |

|

See Terms and Definitions for more detailed descriptions of each term.

While the results of all types of studies may be published, the majority of the published studies, especially in peer-reviewed journals, are hypothesis-based research by academic researchers.

Safety assessments rely on both guideline-based studies and hypothesis-based research. Typically, the results of screening tests and validation studies are not pivotal for the final safety assessment since they are not intended to identify adverse effects. If the study is pivotal to a GRAS determination, then it must be published in some form.

With this common understanding of the system, the workshop's goal is for participants to engage in robust discussion of the four key issues to provide potential opportunities for improvement in the generation and evaluation of scientific information. The areas are

- What are the considerations in identifying and validating adverse health effects?

- What are the best methods to evaluate study designs and data for regulatory decisions?

- How should validation studies be developed and test guidelines be reviewed?

- What problems have been identified with our current regulatory process, and what potential solutions should be considered?

REPORT CONTENTS A

CONSIDERATIONS IN IDENTIFYING AND VALIDATING ENDPOINTS, INCLUDING ADVERSE EFFECTS

Round 1 of the small group discussions will focus on considerations in identifying and validating relevant endpoints, including adverse effects. In essence, we are asking the following question: What should guideline-based, nonclinical studies measure to assess the human health effects of a substance?

To help focus the discussion, we selected four hot topics designed to engage participants. They are

- endocrine disruption

- behavioral impacts

- nanomaterial characterization

- Tox21 and NHANES screens.

At first glance, you may notice that not all of these topics involve health effects. We have included an array of relevant topics, including health effects, characterization of a class of materials that may raise unique hazards, and methods used to screen for markers of exposure to highlight different aspects of the issue.

The discussion of endocrine disruption and behavioral impacts will focus on the contentious issue of whether or not endpoints with positive results in hypothesis-based research constitute or sufficiently predict adverse effects to justify incorporation into guideline-based studies. We selected these two topics because they represent distinct aspects of endpoint identification and validation and would allow us to address the underlying questions. Note that FDA does not have a definition of adverse effect related to chemicals added to food.

The discussion on nanomaterial characterization will look at a different issue: What is the substance being studied? Currently, guideline-based studies do not assess whether or how much of a substance is between 1 and 100 nanometers in a single dimension. Recent research into these nanoscale materials indicates that some substances exhibit unusual physical and chemical properties that may be important toxicologically.

The Tox21 and NHANES discussion will focus on the use of these screening tests as a trigger for more focused hypothesis-based research and, perhaps, guideline-based studies. Tox21 screens use in vitro methods to evaluate the impact of a wide array of chemicals and mixtures on cells. NHANES screens for human exposures by measuring chemicals in a large sample of the general population. In other words, Tox21 is a screen for a substance's potential hazard, and NHANES is a screen for human exposure. Both methods are important to understand the potential health risk posed by a substance. While a positive result in either screening system does not mean the result is an adverse effect, it does indicate the need for additional study that will lead to regulatory decisions.

By examining all three types of issues—adverse health effects, raw material characteristics and results of screening methods to conduct additional studies to identify adverse effects—we can ensure that nonclinical, guideline-based studies are more adequately designed and are more useful and relevant to human health.

Read Full Section: Small Group Discussion Round 1 (PDF)

EVALUATING STUDY DESIGN AND DATA FOR REGULATORY DECISIONS

Round 2 of the small group discussions will shift from a narrow focus on study endpoints to the overall study design. This expanded focus will allow us to build on the previous discussions and deal with specific challenges that have been raised about both guideline-based studies and hypothesis-based research. To help focus the discussion, we selected four topics designed to engage participants. They are

-

dose response

-

transparency

-

study reproducibility

-

use of hypothesis-based research.

FDA's presentation immediately before this round should help prepare you for this discussion by explaining how it assesses the safety of food additives and makes its regulatory decisions. You may want to review the three documents that FDA provided at the end of this binder as background to the discussion.

The first session will focus on whether the methods to develop doses for nonclinical, guidance-based studies need to be modified on the basis of research indicating low-dose effects.

The second session will focus on the challenge of transparency in both hypothesis-based research and guideline-based studies as well as FDA's review of the science. Most stakeholders agree that the results of the studies would be more credible and useful if FDA and independent analysts had access to the raw data, laboratory notes and detailed analysis so they could make their own evaluation. But accomplishing this would be a challenge. In both types of studies, independent analysts cannot access the information. FDA gets access only if a study is

-

conducted by or on behalf of the submitter requesting premarket authorization

-

funded by the federal government and the funding agency requests the information.

The third session will focus on how to ensure that studies evaluated by FDA are reproducible in other laboratories. If the study results are not reproducible, they have limited use in guideline-based studies and should not be the basis of a validated endpoint or toxicity study design. Guideline-based studies comply with GLP standards to provide assurance to FDA that the results are reproducible. Hypothesis-based researchers rely on their peers to evaluate their publications and attempt to reproduce their data. However, funding for study replication is limited.

The fourth session moves beyond the three key issues and takes a broader look at how FDA can make better use of hypothesis-based research directly in its regulatory decisions. FDA often relies on this type of research for clinical studies, epidemiological studies or studies that expand on guideline-based studies. This session is designed to help researchers better understand FDA's needs and to help FDA better understand researchers' capabilities.

Read Full Section: Small Group Discussion Round 2 (PDF)

REPORT CONTENTS B

DEVELOPING AND REVIEWING TEST GUIDELINES

Round 3 of the small group discussions will focus on developing and reviewing test guidelines. These guidelines establish the objectives, general design and endpoints of guideline-based studies. When FDA determines that a test method has been validated and provides useful understanding of the safety of a food additive, it includes the protocol in its Redbook guidance and explains how it should be used. Once this is done, food manufacturers, expert panels and consultants conducting their own safety assessment or preparing a petition to FDA are expected to conduct guideline-based studies consistent with the guidance.

While FDA is our priority, we also want to keep in mind the other organizations that review and approve relevant test guidelines. The most important are the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and, to some extent, the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA).

FDA's presentation at the end of Day 1 and its document on the Redbook in the back of the binder should help you better understand how it reviews and approves test guidelines. The panel presentation on alternative methods to animal testing at the beginning of Day 2 should provide insights into how the system handled a new set of test guidelines.

In Round 3, we are continuing to expand our focus, moving stepwise from specific endpoints in Round 1 to study design in Round 2 and, now, to the incorporation of new or improved study designs into FDA's guidance. Unlike Rounds 1 and 2, we will not focus on a handful of hot topics. In this round, we want to look broadly at all aspects of the issue. To make the discussion more productive, we have divided the issue into two parts:

- Developing test guidelines for review: How are new or improved draft test guidelines developed, validated, funded and submitted to FDA (or another organization) for its consideration?

- Reviewing and approving test guidelines: How does FDA (or another organization) review, manage and approve new or improved draft test guidelines?

Given the breadth of the topic and the importance of having small enough groups to ensure that all participants will be heard, we will have two small group discussions going on simultaneously in each of these two parts.

All groups should also consider whether implementing a step-by-step procedure following the OECD model would be useful and practical under FDA's Good Guidance Practices, and which steps can be taken to make these procedures efficient.

BACKGROUND

The Redbook is an FDA Level 1 guidance document under 21CFR 10.115 Good Guidance Practices. At 21 CFR 10.115, FDA describes the procedures to participate in the development of guidance documents. Any person, institution, stakeholder or agency can

- Provide input on guidance documents

- Suggest areas of guidance development

- Submit drafts of proposed guidance documents

- Suggest revision or withdrawal of any guidance document.

Once a year, FDA publishes in the Federal Register a list of possible topics for future guidance document development or revision. Before and after preparing a draft for a new Level 1 guidance document like the Redbook, FDA seeks public comments in response to the notice, reviews them and incorporates them into the final guidance document as appropriate.

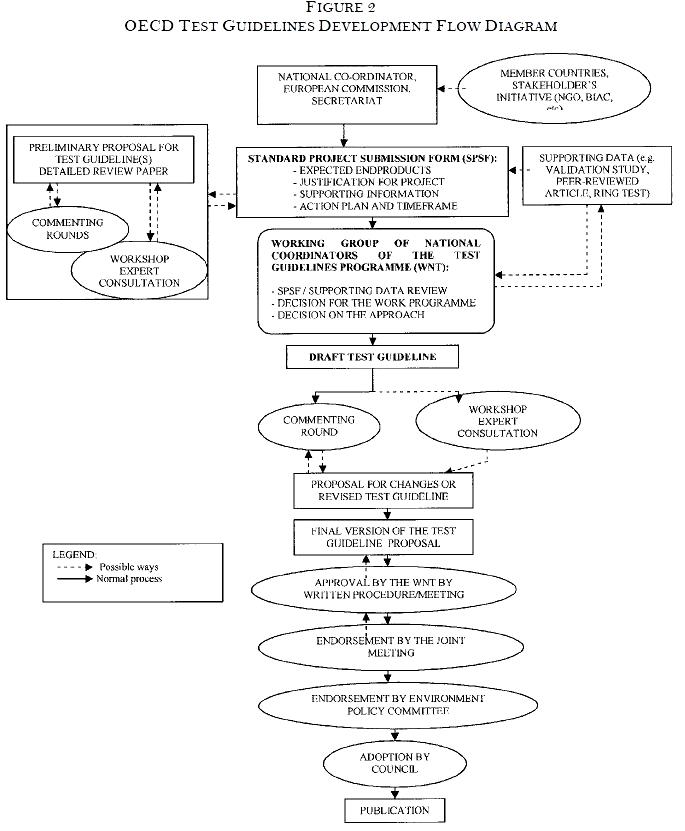

OECD has defined procedures for the creation of new guidelines and updating of current test guidelines under the Test Guidelines Program; these procedures are described in “Guidance Document No. 1 for the Development of OECD Guidelines for Testing of Chemicals.” See Figure 2 for a flowchart of the procedures.

Governments, industry, public interest groups, the scientific community, the European Commission or the OECD Secretariat can submit proposals to develop or update test guidelines. The submission form contains a detailed description of the project and supporting documentation (such as regulatory need, validation status, relevance and reliability) and describes the work plan (deadlines, deliverables and milestones). OECD guidelines and documents are available at no charge online.

The information provided at the time of proposal submission describes

- foreseen or existing regulatory need for such a test (or update)

- contribution to international harmonization of data requirements

- scientific arguments indicating the importance of the test or the modifications

- animal welfare considerations indicating the advantages of the proposed test/procedure with respect to animal use/discomfort without loss of essential information

- a rationale indicating the advantages of the proposed test/procedure with respect to reduced costs without loss of essential information

- supporting documentation; e.g., on the performance of the test method, validation status, or the reliability and relevance of the method.

Read Full Section: Small Group Discussion Round 3 (PDF)

IDENTIFYING AND EVALUATING POTENTIAL SOLUTIONS

Round 4 of the small group discussions will consist of priority-setting sessions to improve any aspects of FDA's evaluation of science to ensure that chemicals added to human food are safe. We want to shift from evaluating specific aspects of the system to assembling the ideas from previous sessions, grouping them into categories, combining them as appropriate, and getting a structured insight into participants' priorities for the ideas.

To help focus the discussion, we divided the system into three areas

- Improving hypothesis-based research

- Improving guideline-based studies

- Refining the regulatory decision-making process.

We recognize that there is significant overlap between the topics. The discussion should not be strictly limited to the specific topic. Also, we may adjust the topics and even add a concurrent session based on the discussions and ideas developed throughout the workshop. Talk with the facilitators and session moderators if you have ideas and comments.

Read Full Section: Small Group Discussion Round 4 (PDF)