New York's Medicaid Drug Cap

A look at the state's new effort to manage pharmaceutical spending

Overview

State governments across the country are examining policies to manage drug spending,1 including in Medicaid,2 which accounted for nearly one-fifth (19.7 percent) of 2015 state general fund expenditures.3

Despite mandatory and supplemental discounts in Medicaid drug purchasing, prescription drugs continue to drive increases in state spending. Federal and state Medicaid programs spent $61 billion on prescription drugs in FY 2016, although significant rebates

The Medicaid Drug Rebate Program (MDRP), created under the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990,5 requires that drug manufacturers provide information about the average price and lowest price—also known as the best price6—paid for a drug by any purchaser. Manufacturers enter into contracts and agree to provide rebates to states based on best price information and the average price of the drug in a market.7 For brand drugs, state Medicaid programs receive rebates amounting to at least 23.1 percent of the average manufacturer price (AMP),8 but discounts often are higher because of inflationary penalties and other rebates.9 The District of Columbia and 46 states, including New York, have also entered into single-state and/or multi-state supplemental rebate agreements with manufacturers to secure additional rebates and reduce prescription drug expenditures.10

States must cover drugs from manufacturers that have entered into these agreements. States are limited to requiring nominal co-payments from beneficiaries in order to restrict coverage, but can also use tools to limit utilization such as prior authorization, quantity limits, Preferred Drug Lists (PDL)—medication lists developed by the state indicating certain drugs as preferred given their clinical significance, cost, and overall efficiencies—and step therapy, which requires a patient to try a preferred drug before a non-preferred drug.11

Given Medicaid’s share of state budgets, legislators continue to look for additional measures to manage state spending within this public health program. One approach is the New York State Medicaid Drug Cap, enacted in April 2017, which is intended to limit the state’s spending on prescription drugs in the program.

New York’s approach

New York instituted a global spending cap for Medicaid in 2011, which imposes a statutory limit on annual growth for the entire program including both prescription drugs and health care services.12 As part of its State Fiscal Year (SFY)13 2018 Health and Mental Hygiene budget passed in April 2017, New York instituted a separate Medicaid drug cap as a focused effort to limit the growth of Medicaid spending on prescription drugs.14 While implementation is ongoing, the New York Department of Health (DoH) predicts that the cap will be triggered in the current SFY.15

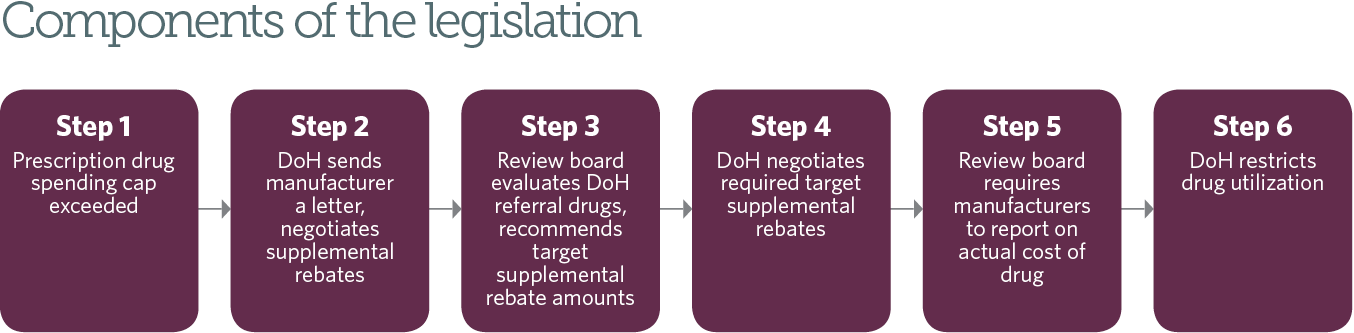

Step 1: Prescription drug spending cap exceeded

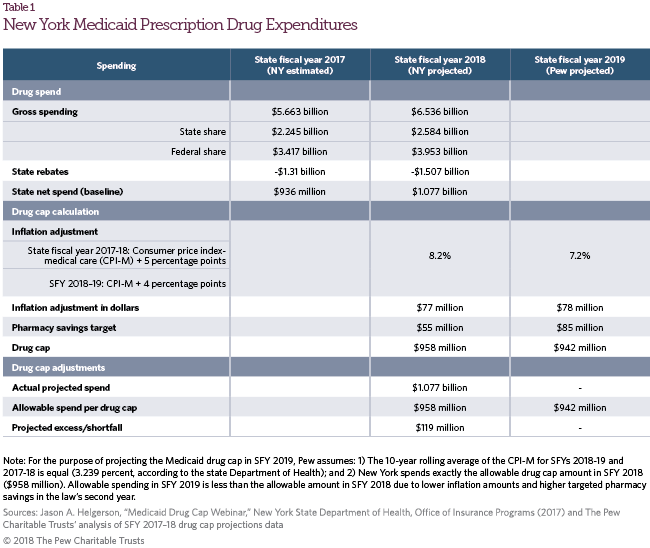

For SFY 2018, net prescription drug spending cannot exceed the 10-year rolling average of medical inflation16 (3.2 percent) plus 5 percentage points (totaling 8.2 percent at the time of the bill’s enactment), minus an additional $55 million.17 The law includes a more limited growth rate for SFY 2019, allowing prescription drug spending to increase at the 10-year rolling average of medical inflation plus 4 percentage points, minus $85 million. The commissioner of health for New York state does not have the authority to create a spending cap after SFY 2019, but the legislature could amend the legislation in future years.

DoH prospectively develops projections for state Medicaid expenditures on prescription drugs,18 reporting spending for each covered drug and for all drugs on a quarterly basis net of rebates in both fee-for-service and managed care plans. If projected spending exceeds the spending cap, the commissioner initiates a process to secure additional rebates for certain drugs.

Step 2: DoH sends manufacturer a letter, negotiates supplemental rebates

Once the DoH determines that state spending on prescription drugs in Medicaid will exceed the drug spending cap, the commissioner identifies specific drugs that are contributing. The commissioner must consider the drug’s actual cost to the state net of rebates, and whether the manufacturer is already offering significant discounts relative to the other drugs covered by the Medicaid program.19 After the law was passed, the commissioner established that the projected spend of a drug must be over $5 million for the drug to have a substantial effect on the Medicaid drug cap, with exceptions for drugs that have significant increases in cost or utilization and outlier drugs contributing to the cap.20 For each drug, the commissioner also recommends preliminary “target supplemental rebate” amounts—manufacturer concessions provided to New York state in addition to federal statutory and state supplemental rebates.

The DoH notifies each manufacturer that its drug(s) will be reviewed by the New York Drug Utilization Review Board (DURB), a 23-member entity that reviews and authorizes prescription drugs and prescribing practices for the state’s Medicaid program.21

After notifying the manufacturer and before DURB review, the DoH can work with manufacturers to negotiate supplemental rebates. If the manufacturer agrees to a rebate that meets the target amount, the rebates would be backdated to take effect on the first day of the SFY, April 1.

Step 3: Review board evaluates DoH referral drugs, recommends target supplemental rebate amounts

If the Commissioner and manufacturer are unable to reach a rebate agreement, the DoH refers these drugs and recommended rebate amounts to the DURB. Thirty days before the DURB’s review, DoH will post the names of the drugs on the state’s website.

The DURB evaluates DoH’s drug recommendations and identifies drugs for which DoH should negotiate additional rebates.22 In deciding whether the DoH should pursue target supplemental rebates for a drug, the law allows the DURB to consider total state spending on the drug and existing manufacturer rebates, as well as other pricing factors such as the drug’s impact on the overall Medicaid spending target, the drug’s “affordability and value” to Medicaid, any “significant and unjustified” price increases, and whether the drug is “priced disproportionately to its therapeutic benefits.”23

Once the DURB identifies drugs to pursue, it must recommend the amount of the target supplemental rebate. In deciding the rebate amount, the DURB can consider information about the drug’s price; cost to the state; value; and effectiveness, including the drug’s cost-effectiveness, existing pharmaceutical equivalents, and publicly available pricing information.24

Step 4: DoH negotiates required target supplemental rebates

After the DURB recommends a target rebate, the Commissioner can require supplemental rebates from the drug manufacturer in an amount equal to or less than the DURB-recommended target rebate amount.25

If the DURB recommends a target rebate and DoH cannot negotiate a required rebate from the manufacturer that is at least 75 percent of the target amount, the Commissioner can waive a provision under current law that allows providers to overrule Medicaid’s prior authorization requirements for drugs not on the PDL.26 The commissioner can also remove requirements27 for managed care entities to cover all medically necessary drugs within several therapeutic classes.28 DoH can apply these additional restrictions for only two drugs at a time and DoH cannot implement waivers in cases where doing so would restrict access to a drug considered to be the only treatment for a particular disease or condition.29

Step 5: Review board requires manufacturers to report on actual cost of drug

If the manufacturer and DoH do not agree to supplemental rebates that DoH finds satisfactory,30 the commissioner can require the manufacturer to submit proprietary information about the drug, including: the actual cost of developing, manufacturing, producing, and distributing the drug; research and development costs; administrative, marketing, and advertising costs; utilization; prices to various purchasers; average rebates and discounts; and average profit margins.31 This information will be kept confidential and used to establish target supplemental rebate amounts.

Step 6: DoH restricts drug utilization

When state Medicaid expenditures are still expected to exceed the cap, the commissioner may institute utilization restrictions and cost containment efforts. For a manufacturer that did not agree to target supplemental rebates, the commissioner can impose utilization management on all of the manufacturer’s drugs, not just the one targeted for supplemental rebates. Utilization management tools include requiring prior authorization, directing managed care plans to stop covering the drugs, and promoting cost effective and clinically appropriate drugs32 in place of them. Manufacturers may also accelerate rebates, though it is unclear what form this would take. The commissioner must provide written notice to the legislature 30 days prior to restricting utilization unless the action is necessary in the fourth quarter of the fiscal year.

Implementation status

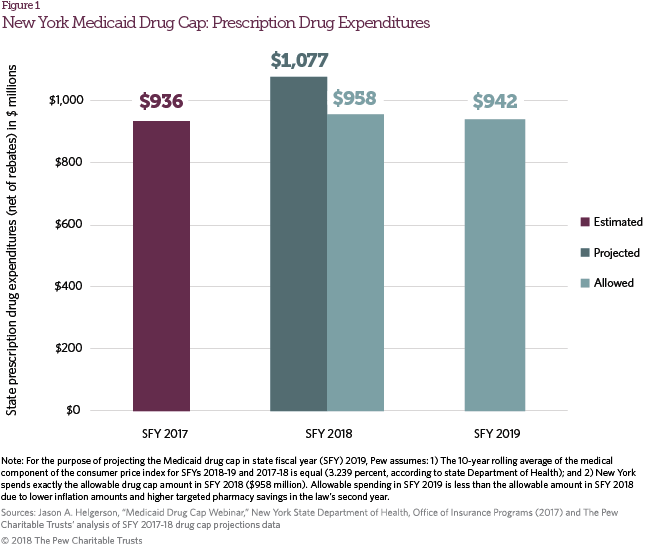

In August 2017, the New York DoH projected that state Medicaid drug spending would increase from $936 million in SFY 2017 to $1,077 million in SFY 2018, triggering cap provisions. The DoH predicted that Medicaid drug expenditures would exceed the Medicaid drug cap by $119 million—a 15.1 percent increase in state Medicaid expenditures compared with the allowable 2.4 percent.33

Per legislative requirements, the commissioner studied the effect of each drug on Medicaid spending to determine whether to refer the drug to the DURB for target rebates. The commissioner identified 30 drugs made by 12 manufacturers that had a “significant impact on the drug cap” (accounting for 37 percent of state Medicaid drug spending).34 The commissioner sent letters to the manufacturers of these 30 drugs on Aug. 25. In February 2018, DoH reported to the DURB that the state secured new drug cap rebate agreements for six drugs and was in negotiations for another 12. By late March, the DoH had not referred any drugs to the DURB. The state reports that it is likely to meet the drug cap savings target of $958 million.35

Questions for policymakers

Policymakers should consider whether New York’s approach to reining in Medicaid expenditures on drugs is an effective strategy that can withstand potential legal challenges. New York’s drug cap directly reduces drug spending using targeted savings amounts. Prior to the law, New York entered into single-state, multi-state, and managed care arrangements to secure supplemental rebates from drug manufacturers.36 All savings from the drug cap would be in addition to the existing supplemental rebates. Under the drug cap, the state is expected to save $119 million in SFY 2018. While these savings are equivalent to 11.1 percent of the projected state pharmacy spend in SFY 2018, after accounting for rebates, they are a relatively small share of overall state Medicaid spending—0.61 percent of $19.5 billion in projected state Medicaid costs in SFY 2018.37

Medicaid has an open formulary38 design, meaning that states must cover all drugs from manufacturers that enter into a federal Medicaid drug rebate agreement. States have some ability to favor certain drugs and limit utilization, but the federal Medicaid statute prohibits states from restricting patient access to a drug if it is the only treatment available for a specific disease or condition.39 New York statute requires Medicaid coverage of all medically necessary services and supplies necessary to prevent, diagnose, correct, or cure conditions, as determined by a physician.40 Private insurers, on the other hand, have closed formularies and can refuse to cover certain drugs. Using the threat of non-coverage, private insurers can leverage competition between manufacturers to obtain discounts in exchange for a preferred formulary placement.

Under this law, New York is attempting to leverage the benefits of a closed formulary design while still providing medically necessary treatment.41 The state is seeking to secure additional supplemental rebates through utilization management techniques common to private insurers, such as removing drugs from formularies, requiring prior authorization, and promoting the use of other clinically appropriate drugs. The state issued assurances that beneficiaries should continue to receive needed drug therapies,42 but litigation is possible if the law has the effect of denying patient access to certain necessary drugs. Other states have faced lawsuits from manufacturers and patients in response to attempts to restrict patient access to drugs. For example, a number of states have been sued for placing restrictions on drug treatments.43

The impact of the drug cap will depend on whether the law is implemented as described as well as manufacturers’ willingness to offer additional rebates. The law creates new state authorities to regulate Medicaid prescription drug spending but it is not yet clear to what extent DoH will leverage these authorities to negotiate deeper rebates and potentially remove drugs from the state’s formulary. In addition, while New York Medicaid’s 6.6 million enrollees represent a large market (8 percent of the country’s Medicaid beneficiaries),44 it is not known whether the threat of stricter utilization management for certain drugs will provide manufacturers a sufficient incentive to offer additional rebates on top of existing mandatory and voluntary discounts. The law’s limitation on applying utilization management tools to two drugs at a time may hinder the state’s efforts to negotiate with multiple manufacturers.

Notably, the law does not regulate the price of prescription drugs and drug spending in other state and federal programs, such as state employee health plans, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, Medicare, and Veterans Health Administration, or in the private market, including employer-sponsored coverage.45

Acknowledgments

This issue brief was prepared by Pew staff member Alisa Chester of Pew’s Drug Spending Research Initiative, with assistance from colleagues Sean Dickson, Nicole Silverman, Demetra Aposporos, Cindy Murphy-Tofig, and Richard Friend.

Appendix I

Other Legislative Provisions Included in New York's Medicaid Drug Cap

Review board changes

The law amends the DURB, which existed prior to the Medicaid drug spending cap, by adding four new positions47 for a total of 23 members and updating its mission to include recommending target supplemental drug rebates.48

Generic CPI penalty49

For generic drugs, manufacturers must provide rebates to the state health department for any drug that has increased more than 300 percent of its state maximum acquisition cost between April 1, 2016, and March 31, 2017. This legislation also requires manufacturer rebates for generic drugs that increased more than 75 percent of the state maximum allowable cost on or after April 1, 2017, compared to the prior 12 months—a standard that will lead more generic drug manufacturers to pay the inflationary penalty for generic drugs.

Endnotes

- See, for example, the Prescription Drug State Database and available overviews from the National Conference of State Legislatures or the Center for State Rx Drug Pricing from the National Academy for State Health Policy. National Conference of State Legislatures, “2015-2018 State Legislation on Prescription Drugs,” Prescription Drug State Database, http://www.ncsl.org/research/health/prescription-drug-statenet-database.aspx.

- Medicaid is a public health program jointly administered by the federal government and states that primarily serves low-income people (children, parents, and, in some states, other adults) and some medically needy patients. The Federal Medical Assistance Percentages determines the federal share of Medicaid spending and ranges from 50 percent to 75 percent, with exceptions for certain services and populations.

- National Association of State Budget Offices, “State Expenditure Report: Examining Fiscal 2014-2016 State Spending” (2016), available at http://www.nasbo.org/reports-data/state-expenditure-report.

- Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, “Medicaid Gross Spending and Rebates for Drugs by Delivery System, FY 2016 (millions)” (2017), https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/EXHIBIT-28.-Medicaid-Gross-Spending-and-Rebates-for-Drugs-by-Delivery-System-FY-2016-millions.pdf.

- P.L. 101-508.

- “Best price” is the lowest manufacturer price paid for a drug by any purchaser, but it includes many significant exceptions, such as rebates to pharmacy benefit managers and Medicare Part D plans. 42 U.S.C. 1396r–8(c)(1)(C) (2009).

- Federal payments for drugs in the Medicaid program are based on statutory formulas. In general, state Medicaid programs receive manufacturer rebates amounting to 23.1 percent of average manufacturer price (AMP) or AMP minus best price (the manufacturer’s lowest price inclusive of discounts and rebates) for brand-name drugs and 13 percent of AMP for generic drugs. AMP is an amount paid to manufacturers by wholesalers that distribute to retail pharmacies, as well as retail pharmacies purchasing drugs directly from manufacturers, and is used to calculate drug rebates for Medicaid. The price includes discounts or rebates from manufacturers to wholesalers or pharmacies. If a drug’s price increases at a rate faster than the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U), a manufacturer must provide additional rebates to meet the inflationary penalty. According to one Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Inspector General report, inflationary penalties accounted for 54 percent of total Medicaid rebates. Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Inspector General, “Medicaid Rebates for Brand-Name Drugs Exceeded Part D Rebates by a Substantial Margin” (2015), https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-03-13-00650.pdf.

- 42 U.S.C. 1396r–8(c)(1)(C).

- Ibid.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “Medicaid Pharmacy Supplemental Rebate Agreements (SRA), as of September 2017” (2017), https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid-chip-program-information/by-topics/prescription-drugs/downloads/xxxsupplemental-rebates-chart-current-qtr.pdf.

- Social Security Act 42 U.S.C. §1916(a)(3) and §1916A(c)(2), codified at 42 U.S.C. § 13960.

- New York Public Health Law § 280.

- New York’s state fiscal year runs April 1 through March 31. Fiscal year 2018 began April 1, 2017, and will end March 31, 2018.

- New York Senate Bill 2007B, http://legislation.nysenate.gov/pdf/bills/2017/S2007B.

- Jason A. Helgerson, “Medicaid Drug Cap Webinar,” New York State Department of Health, Office of Insurance Programs (2017) https://www.health.ny.gov/health_care/medicaid/regulations/ global_cap/docs/2017-8-29_medicaid_drug_cap.pdf

- Medical care component of the Consumer Price Index (CPI M).

- Note that this applies only to state spending on is net of rebates and supplemental rebates. The state of New York receives a 50 percent FMAP for Medicaid expenditures, meaning that for every $1 the state spends on Medicaid, the federal government matches $1. The FMAP varies for some populations and services.

- Spending is state-only funds (excluding federal matching funds) and inclusive of all delivery systems (fee-for-service and managed care). Federally mandated rebates and state supplemental rebates (from contracts and from the spending cap legislation) are included in total spending.

- New York Public Health Law § 280.3(d).

- Helgerson, “Medicaid Drug Cap Webinar.”

- The commissioner appoints members to serve a three-year term and who must represent industries in health care, pharmacy, consumer advocacy, state government, economics, and more.

- New York Public Health Law § 280.5(d). Drugs that already have supplemental target rebate agreements, per this statute, cannot be referred to the DURB for additional rebates. The statute also restricts manufacturers from paying out additional rebates to managed care providers, including pharmacy benefit managers, if they have already entered into supplemental rebate agreements with these organizations.

- New York Public Health Law § 280.4.

- Specifically, the DURB can consider information about the drug’s price provided publicly or by the state; information related to value-based pricing; the seriousness and prevalence of the disease or condition treated by the drug; drug utilization; drug effectiveness; savings from reduced medical care need, including hospitalization, because of the drug; average wholesale price, wholesale acquisition cost, retail price, and cost to Medicaid minus rebates; number of manufacturers for generic drugs; pharmaceutical equivalents; information supplied by the manufacturer on the price of the drug relative to development and therapeutic benefit of the drug.

- New York Public Health Law § 280.5(a).

- New York Public Health Law § 273.3(b).

- New York Social Services Law § 364-j(25); New York Social Services Law § 364-j(25-a).

- Under current law, managed care providers must cover all “medically necessary” drugs in the atypical antipsychotic, antidepressant, anti-retroviral, anti-rejection, seizure, epilepsy, endocrine, hematologic and immunologic therapeutic classes, including nonformulary drugs. Should the DURB levy utilization restrictions on a manufacturer’s drugs, this allows managed care entities to remain in compliance with existing state Medicaid laws. New York Social Services Law § 364-j(25); New York Social Services Law § 364-j(25-a).

- New York Public Health Law § 280.5(c).

- New York Public Health Law § 280.6(a).

- The drug manufacturer is required to submit: actual cost of developing, manufacturing, producing, and distributing the drug; research and development costs; administrative and marketing costs; utilization; prices charged to purchasers outside the United States; prices charged to purchasers in the United States including pharmacies, wholesalers, and other direct purchasers; average rebates and discounts; average profit margins over five years and average projected profit margins. New York Public Health Law § 280.5(d).

- New York Public Health Law § 280.7(a).

- Helgerson, “Medicaid Drug Cap Webinar.

- Ibid.

- Janet Zachary-Elkind and Michael Dembrosky, “Drug Cap,” New York State Drug Utilization Review Board meeting, New York State Department of Health (Feb. 15, 2018), https://www.health.ny.gov/events/webcasts/2018/2018-02-15_dur.htm.

- New York participates in single-state Medicaid pharmacy supplemental rebate agreements as of Jan. 1, 2010, multi-state agreements as of Jan. 1, 2006, and supplemental rebate collections for managed care organizations as of Oct. 1, 2014. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “Medicaid Pharmacy Supplemental Rebate Agreements (SRA), as of September 2017” (2017), available https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid-chip-program-information/by-topics/prescription-drugs/downloads/xxxsupplemental-rebates-chart-current-qtr.pdf

- New York State Department of Health, “Medicaid Global Spending Cap Report” (2017), https://www.health.ny.gov/health_care/medicaid/regulations/global_cap/ monthly/sfy_2017-2018/docs/june_2017_report.pdf.

- A formulary is a list of brand-name and generic drugs that payers cover, typically organized in tiers. Patients are required to pay different out-of-pocket costs for drugs in different tiers.

- 42 U.S.C. 1396r–8(d)(4)(C).

- New York Social Services Law § 365-a.2.

- Ibid.

- New York State Department of Health, “Medicaid Drug Cap: Frequently Asked Questions - #1,” revised February 2018, https://www.health.ny.gov/health_care/medicaid/regulations/global_cap/2017-09-22_faqs.htm.

- See, for example, cases for Hepatitis C restrictions in Ryan et. al v. Birch, (U.S. District Court, Colorado); B.E. et. al v. Teeter, (U.S. District Court, Western District of Washington); and Jackson v. Secretary of Indiana Family and Social Services Administration (U.S. District Court, Southern District of Indiana).

- Kaiser Family Foundation, “Medicaid Enrollees by Enrollment Group FY 2014,” State Health Facts, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/distribution-of-medicaid-enrollees-by-enrollment-group

- An earlier version of the New York law allowed the DURB to set a benchmark price for certain high-cost drugs. If a drug exceeded the amount of the benchmark price, the manufacturer would be required to offer an additional Medicaid rebate and both manufacturers and wholesalers would pay an additional surcharge.

- New York Social Services Law § 369-bb.

- The four additional members include two health care economists, an actuary, and a representative of the Department of Financial Services.

- New York Social Services Law § 369-bb.

- New York Social Services Law § 367-a.7.

- New York Public Health Law § 280.2.

- Helgerson, “Medicaid Drug Cap Webinar.”

- New York Public Health Law § 280.3(d).

- Helgerson, “Medicaid Drug Cap Webinar.”

- New York Public Health Law § 280.4.

- Ibid.

- New York Public Health Law § 280.5(e).

- New York Public Health Law § 273.3(b).

- New York Social Services Law § 364-j(25); New York Social Services Law § 364-j(25-a).

- New York Public Health Law § 280.5(c).

- New York Public Health Law § 280.6(a).

- New York Public Health Law § 280.6(b).

- New York Public Health Law § 280.6(a).

- New York Public Health Law § 280.7(a).