Use of State Medicaid Inflation Rebates Could Discourage Drug Price Increases

New inflation penalties could reduce drug costs for all payers

List prices for prescription drugs—set by the manufacturer before discounts and rebates—have grown faster than the rate of inflation.1 In 2015, average drug list prices increased by 6.4 percent, while general inflation only increased by 0.1 percent. 2 Although price concessions, primarily in the form of rebates paid to pharmacy benefits managers, offset much of this price growth, drug spending has continued to increase each year.3 This practice contributed to rising health care costs, particularly out-of-pocket spending by some consumers.

An inflation adjustment in the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program reduces the impact of price increases on Medicaid spending.4 However, because there is a ceiling on this adjustment, it may not discourage manufacturers from raising prices sharply. Increasing the size of the inflation adjustment could lead manufacturers to lessen price hikes overall, leveraging the size of the Medicaid program to reduce drug costs for all payers.

Additional rebates for price increases greater than inflation

Under federal statute, manufacturers that participate in Medicaid must pay rebates to state Medicaid departments to offset drug spending. There are two components to the rebates: a base rebate (23.1 percent for brand drugs and 13 percent for generic drugs) and an inflation rebate, indexed to the commonly used consumer price index (CPI-U).5 Under the inflation rebate, the manufacturer must discount the difference between the current average price of the drug and the inflation-adjusted list price of the drug. For example, if a manufacturer increases the price of a drug from $100 to $115 but the inflation-adjusted price would be only $102, the manufacturer must pay Medicaid a $13 inflation rebate.

In 2010, the Medicaid rebate amount, including both the base rebate and the inflation rebate, was capped at the drug’s average manufacturer price (AMP).6 That formula results in a $0 cap, which, once reached, may create a misaligned incentive for a manufacturer to raise prices for other payers even more, since Medicaid revenue would not be reduced further. Even in cases where a drug has reached the $0 cap, manufacturers are encouraged to maintain participation in the Medicaid rebate program. In order for any of a manufacturer's drugs to be covered under Medicaid or Medicare Part B, the company must enter into an agreement with the federal government to offer rebates on all products the manufacturer sells.7

Proposal to reduce price increases and state drug spending

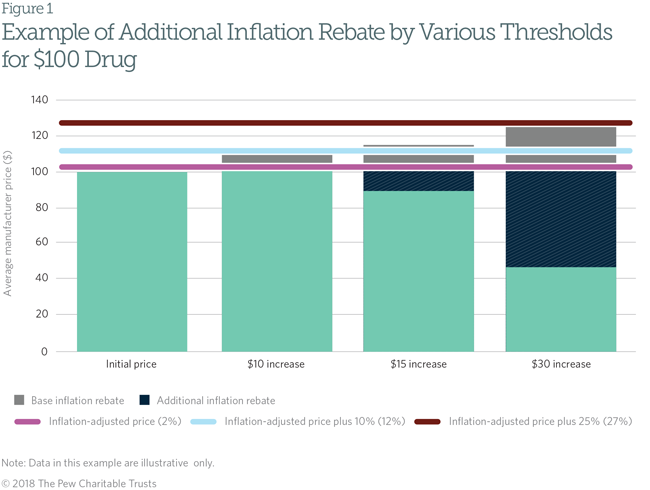

State Medicaid programs could reduce their drug spending, and discourage manufacturers from making large price increases, by requiring manufacturers to pay higher inflation rebates in order to be included on the state’s Medicaid preferred drug list (PDL). States use PDLs in Medicaid to encourage manufacturers to offer voluntary discounts in exchange for Medicaid’s preferring that manufacturer’s drug to those of competitors. This policy would allow states to require manufacturers that raise their drug’s price above a certain threshold to provide an additional inflation rebate if they wish to be included on the state’s PDL. For example, if a manufacturer increased a drug’s price by more than 10 percent above the inflation-adjusted price, that company could have to pay double the inflation penalty; if the manufacturer did so by more than 25 percent above inflation, it could have to pay three times the penalty. The manufacturer would agree to pay these rebates even if the total rebate amount exceeded the price of the drug. Figure 1 shows how this policy would work.

This system would discourage a manufacturer from large drug price increases by magnifying its financial liability in Medicaid. Manufacturers may find it more profitable to raise prices in line with the rate of inflation rather than pay larger rebates to state Medicaid programs, limiting price growth for all payers.

Considerations for state policymakers

Because supplemental state inflation rebates would be a voluntary condition of PDL inclusion, manufacturers of drugs that have undergone large price increases may choose to forgo PDL inclusion to avoid paying them, reducing the state’s ability to manage drug use or negotiate additional rebates. To deter this, states could require that manufacturers pay supplemental inflation rebates on all applicable products as a condition of PDL placement for any other drugs the manufacturer sells. States may also need additional staff to administer the new rebate program and to perform oversight functions.

To reduce these barriers, states could introduce additional inflation rebates only for selected drug classes with frequent or large price increases, such as brand and certain generic drugs. States could also form partnerships with other states to administer an inflation rebate program, following 30 states that have already implemented supplemental rebate agreements with other states.8 Multistate participation would increase manufacturers' financial liability for large price increases and allow states to share the cost of administration. A successful additional inflation penalty would create a greater market incentive for manufacturers to take smaller price increases overall, benefiting all payers.

Endnotes

- Stephen Schondelmeyer and Leigh Purvis, “Trends in Retail Prices of Prescription Drugs Widely Used by Older Americans: 2006 to 2015,” AARP Public Policy Institute (December 2017),

https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2017/11/trends-in-retail-prices-of-prescription-drugs-widely-used-by-older-americans-december.pdfhttps://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2017/11/trends-in-retail-prices-of-prescription-drugs-widely-used-by-older-americans-december.pdf. - Ibid.

- IQVIA, “Medicine Use and Spending in the U.S.: A Review of 2017 and Outlook to 2022” (2018), https://www.iqvia.com/institute/reports/medicine-use-and-spending-in-the-us-review-of-2017-outlook-to-2022.

- 42 U.S.C. § 1396r–8(c)(2).

- 42 U.S.C. § 1396r–8(c).

- 42 U.S.C. § 1396r–8(c)(2)(D).

- 42 U.S.C. § 1396r–8(a)(1).

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “Medicaid Pharmacy Supplemental Rebate Agreements (SRA) as of March 2018,” accessed June 7, 2018, https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid-chip-program-information/by-topics/prescription-drugs/downloads/xxxsupplemental-rebates-chart-current-qtr.pdfhttps://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid-chip-program-information/by-topics/prescription-drugs/downloads/xxxsupplemental-rebates-chart-current-qtr.pdf

.