Steep Drop Since 2000 in Number of Facilities Confining Juveniles

Decline of 42% coincides with reduction in population of youth in custody

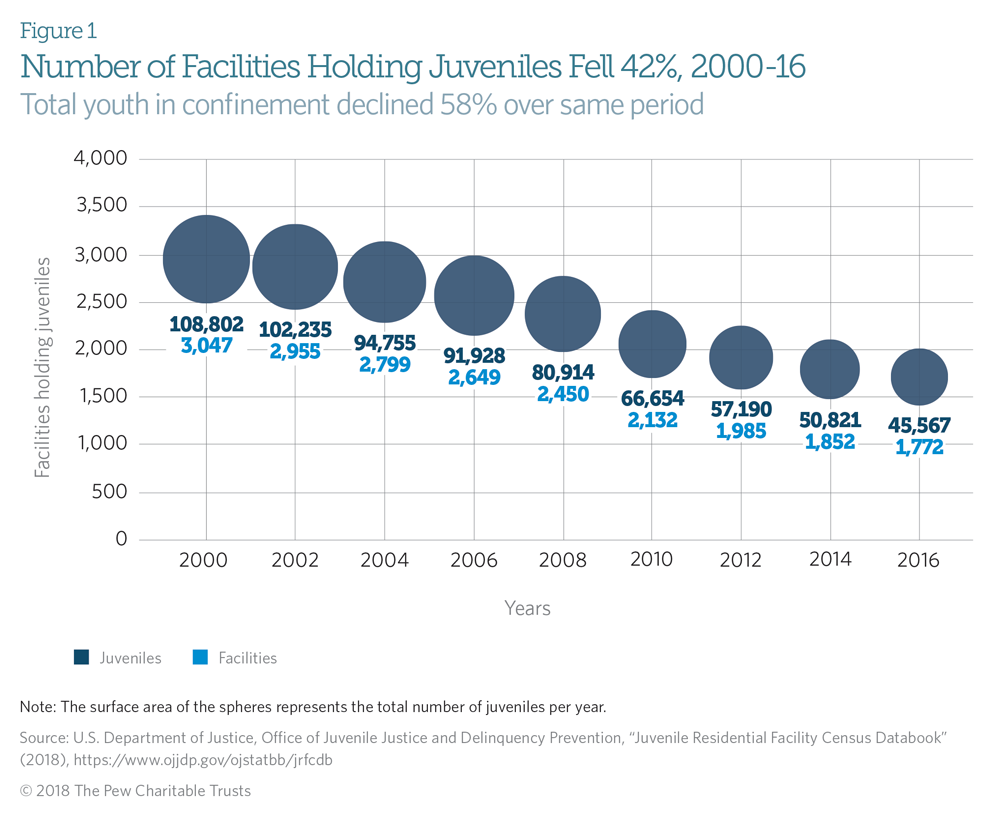

The number of residential facilities holding youth in custody within the juvenile justice system fell 42 percent nationwide between 2000 and 2016, according to newly released data from the Juvenile Residential Facility Census Databook. A biennial census of the sites holding youth as well as the number of youth in custody found that the total number of facilities dropped from 3,047 to 1,772 in that period.

The decline comes in large part because of the significant reduction in the number of youth in custody. Between 2000 and 2016, the number in residential placement dropped 58 percent, according to the databook, which is compiled by the U.S. Census Bureau for the Justice Department’s Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. In addition, the proportion of sites operating under capacity increased 21 percentage points in that 16-year period. In 2016, nearly 4 in 5 facilities, or 78 percent, had empty beds. Many more youth, therefore, were living in full or overcrowded facilities in 2000 than two years ago.

A 2015 issue brief from The Pew Charitable Trusts described a growing body of research showing that the costly practice of confining juveniles is generally no more likely to reduce recidivism than is keeping them in their own homes for treatment and that confinement can actually increase the likelihood of certain youth reoffending. On the other hand, evidence-based, in-home treatment options, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, have been shown to produce substantial reductions in recidivism.

In recent years, some states have found ways to make more effective use of resources once dedicated to residential juvenile facilities. For example, Kansas policymakers determined that group homes there had failed to improve outcomes for youth in their care and that those adjudicated delinquent for misdemeanors made up too large a share of out-of-home placements. That led lawmakers in 2016 to pass S.B. 367, a measure that prohibits the use of group homes for most youth in the juvenile justice system and significantly limits the circumstances under which they can be sent to residential placement. As a result, Kansas has closed one of its two remaining correctional facilities and more than 90 percent of its group home beds. That allowed the state to shift millions of dollars annually to community-based services for youth remaining at home.

Similarly, South Dakota’s S.B. 73, enacted in 2015, focused out-of-home placements on youth who posed the greatest threat to public safety while redirecting resources toward community programs for those charged with less serious offenses. South Dakota closed its only remaining secure juvenile facility in 2016, creating substantial savings that could be reinvested in community-based programs and grants to counties to help them divert those charged with low-level offenses from the juvenile justice system.

A recent report by the Council of Juvenile Correctional Administrators provides advice and tools to help juvenile justice agencies close facilities responsibly and consider such closures as a component of broader efforts to change juvenile justice systems. The guidance is intended to help policymakers and agency leaders who are closing facilities to:

- Meet the needs of youth, families, and staff.

- Take advantage of changes in placements, staffing, and funding to improve care, practice, and conditions of confinement.

- Preserve and reinvest resources required to meet the needs of young people and achieve the agency’s mission.

Falling crime rates and reductions in residential placement may contribute to recent facility closures. Those factors can also be catalysts for further change, increasing the resources available for reinvestment in a continuum of evidence-based supervision and services. When carried out in ways that support youth, families, staff, and communities, closures can be an important component of state and local juvenile justice reform strategies.

Dana Shoenberg is a senior manager of juvenile justice research and policy and Erinn Broadus is a research associate with The Pew Charitable Trusts’ public safety performance project.