Shark Conservation Sees Global Gains in 2016

New protections offer hope for most vulnerable species, continuing focus on declining populations

New restrictions on trade of animal products should help populations of three species of thresher sharks, including pelagic threshers like these, off Malapascua Island, Philippines, recover from declines brought on by heavy fishing.

© Steve de Neef

To stay alive and keep oxygen flowing through their gills, some shark species must swim constantly. That’s pretty much how The Pew Charitable Trusts’ shark conservation team felt throughout 2016 as we spanned the globe—from the U.S. and the Caribbean to China, Africa, and remote Pacific islands—securing major policy wins to protect numerous species of the megafauna that are being killed faster than they can recover.

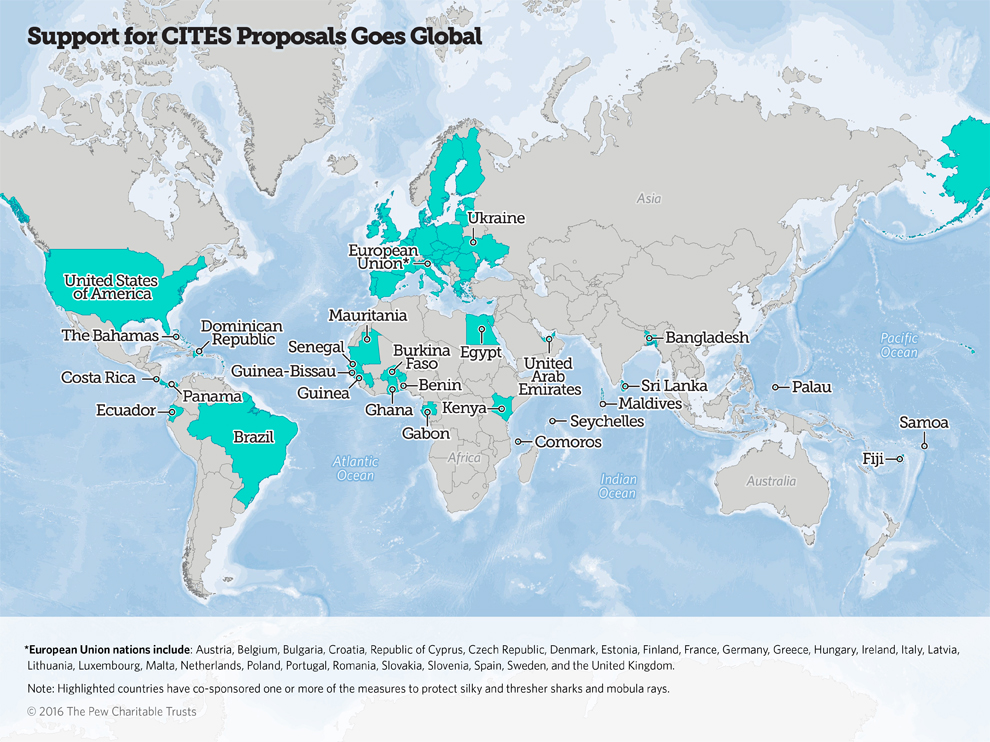

Our year of perpetual motion began in January at the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) Standing Committee meeting in Geneva. There, representatives from three countries—Sri Lanka, the Maldives, and Fiji—announced proposals to add, respectively, three species of threshers sharks, silky sharks, and nine species of mobula rays to CITES Appendix II, which requires that any international trade in a species be proven sustainable. The goal was to duplicate the successful effort that garnered Appendix II listings in 2013 of five shark species (porbeagle, three species of hammerhead, and oceanic whitetip) and two species of manta ray, which provided relief to the species that were at the greatest risk of extinction due to their valued fins and gill plates in international trade.

Mobula rays take on a glow as they swim near the surface. These animals need protected because they are fished heavily for their gill rakers.

© Shawn Heinrichs

By April, more than 50 countries had agreed to co-sponsor one or more of the CITES shark and ray measures—more countries than had ever signed on to a CITES proposal. But our work had only begun.

From May through September, Pew and our partners ramped up momentum for the proposed protections by hosting workshops in Samoa, Sri Lanka, the Maldives, Senegal, South Africa, Armenia, Oman, and the Dominican Republic. At these sessions we provided attendees with information about the threats facing the CITES proposed shark and rays species and fin-identification training, including instructions on how to spot the fins and gill plates of Appendix II-listed species, which helped ease attendees’ concerns over enforcement of the trade restrictions.

After the workshops, it was on to the main event: the CITES 17th Conference of the Parties (CoP17) in Johannesburg, where the proposals we’d worked so hard to advance would be decided. On Oct. 4, the verdict came in: Two-thirds of the 182 CITES parties voted to add silky sharks, the three species of thresher sharks, and the nine species of mobula rays to Appendix II!

A screen at the CITES Conference of the Parties meeting in Johannesburg in October shows the final vote count for Proposal 42, which added silky sharks to Appendix II, banning unsustainable trade in the species.

© The Pew Charitable Trusts

Pew’s shark campaign celebrates the CoP17 CITES Appendix II listings with allies from around the world.

© The Pew Charitable Trusts

With these new listings, the percentage of sharks worldwide threatened by the fin trade that are now protected under CITES doubled, from 10 to around 20 percent, giving these species a chance to recover from heavy fishing that has driven population declines of more than 70 percent throughout their range.

Throughout the year—before, during, and after the CITES effort—Pew was also advocating for shark protections in the regional bodies that govern fisheries on the high seas around the world, where many sharks are caught. In July, we attended the Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission meeting in La Jolla, California, where the key fisheries management body banned the use of fishing gear that targets sharks during their migratory months, which will lead to reduced silky sharks catches.

In 2016, in addition to the CITES trade measure, silky sharks gained protection under the Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission, which reduced targeted catch of the species during migratory months in waters it regulates.

© Jim Abernethy

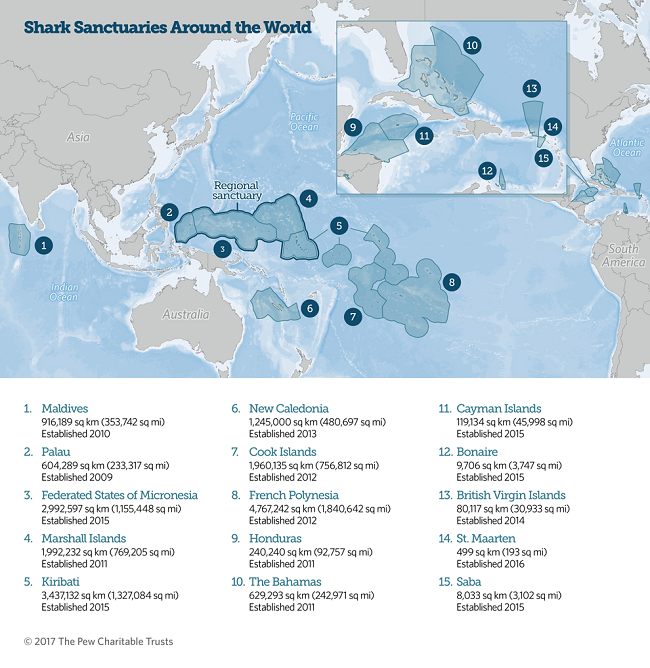

In June, St. Maarten and the Cayman Islands banned all commercial fishing of sharks in their waters, and Kiribati followed suit in November, establishing the world’s second largest shark sanctuary, covering 1.3 million square miles (3.4 million square kilometers). That move also expanded the Micronesia Regional Shark Sanctuary, which was created in 2015.

Prime Minister William Marlin of St. Maarten announces a national shark sanctuary in his country’s waters in June.

© Duncan Brake

Boats sit idle off Tarawa, Kiribati. Sharks are now protected in a sanctuary in the country’s waters, announced in November.

© The Pew Charitable Trusts

With those announcements, 15 shark sanctuaries worldwide now provide more than 7.34 million square miles (19 million square kilometers) of ocean—an area bigger than South America—where commercial shark fishing is banned and these majestic creatures can begin to recover from past overexploitation.

Capping off the year in China, Pew staff celebrated the culmination in November of a two-year partnership with Beijing-based Link Capital Nature & Social Affairs Center to secure “no shark fin” commitments from over 100 prominent Chinese enterprises, including dozens of China Fortune 500 corporations such as Alibaba, Lenovo, Sina, and Weibo. The businesses pledged to not serve shark fin soup at company events, not order it during business meals, and halt all sales and transport of shark fins.

Even after such an exhausting and productive 2016, Pew has significant work ahead to help reverse the precipitous decline in shark numbers globally. The campaign and its partners will continue to ensure that governments comply with existing measures and will advocate for expanding protections for sharks and rays wherever they roam.

Luke Warwick directs the global shark conservation initiative for The Pew Charitable Trusts.