California Proposes to Harness Revenue Volatility to Rebuild Rainy-Day Funds

As revenue recovers, California is seeking to rebuild its financial cushion in a way that leaves it better prepared for the next economic downturn. After facing a shortfall almost one-third the size of its entire budget in fiscal year 2012, California is currently debating what to do with a portion of its anticipated $6 billion surplus and how best to save for future declines in revenue.1

A proposal to change how the state regularly sets aside savings is slated to appear on the ballot in fall 2014, but Governor Jerry Brown has put forth an alternative recommendation for replenishing California’s reserves and managing state revenue volatility. The Legislature will determine which of these measures is ultimately set before voters on Nov. 4, when Californians will have final say on a state policy for restructuring the rainy-day fund.2

History of California’s rainy-day fund

Concerned about fluctuating revenue during boom-bust cycles, California created its Budget Stabilization Fund in 2004 through a voter-approved constitutional amendment. Beginning in 2007, 3 percent of general fund revenue was to be deposited into the reserve account annually, regardless of economic performance in any given year.3 After the first deposit, however, the recession struck and officials suspended further payments.

During the Great Recession, California drained its financial reserves as it struggled to close the nation’s largest budget gap.4 By the end of fiscal 2013, reserve fund balances began to recover but still amounted to slightly more than three days’ worth of operating costs. Only two states had smaller financial cushions as a share of operating expenses.5 But California’s revenue picture has brightened, in part, because of economic and stock market growth and increases in sales and income tax rates. At the same time, cuts have reduced spending levels. The state is now considering ways to allocate the resulting surplus and rebuild savings for the next economic downturn.

Even before state revenue fully recovered, California policymakers began seeking stronger controls over the Budget Stabilization Fund. In 2010 the Legislature agreed to ask voters to approve a ballot measure that, for the first time, would link deposits to unanticipated revenue. Whenever total tax collections surpassed a 20-year trend, the excess would be deposited into the reserve fund.6 The proposal, known as Assembly Constitutional Amendment No. 4, or ACA 4, also would raise the maximum balance of the fund, create tighter restrictions on withdrawals, and make it harder to defer deposits. The measure is scheduled to appear before voters this fall.

The governor’s plan

In January, Gov. Brown offered an alternative policy for deposits to the Budget Stabilization Fund. During his term, he has prioritized saving for the future, and he recommended replenishing the fund by capturing some of the windfall generated by the state’s tax on capital gains—the profit from the sale of investments or other assets—during good economic times. Meanwhile, to get a head start on rebuilding the state’s reserves, Gov. Brown also proposed a one-time, $1.6 billion deposit to the rainy-day fund from the state’s expected surplus. The governor is asking the Legislature to replace the plan slated to go before voters this fall with his proposal.

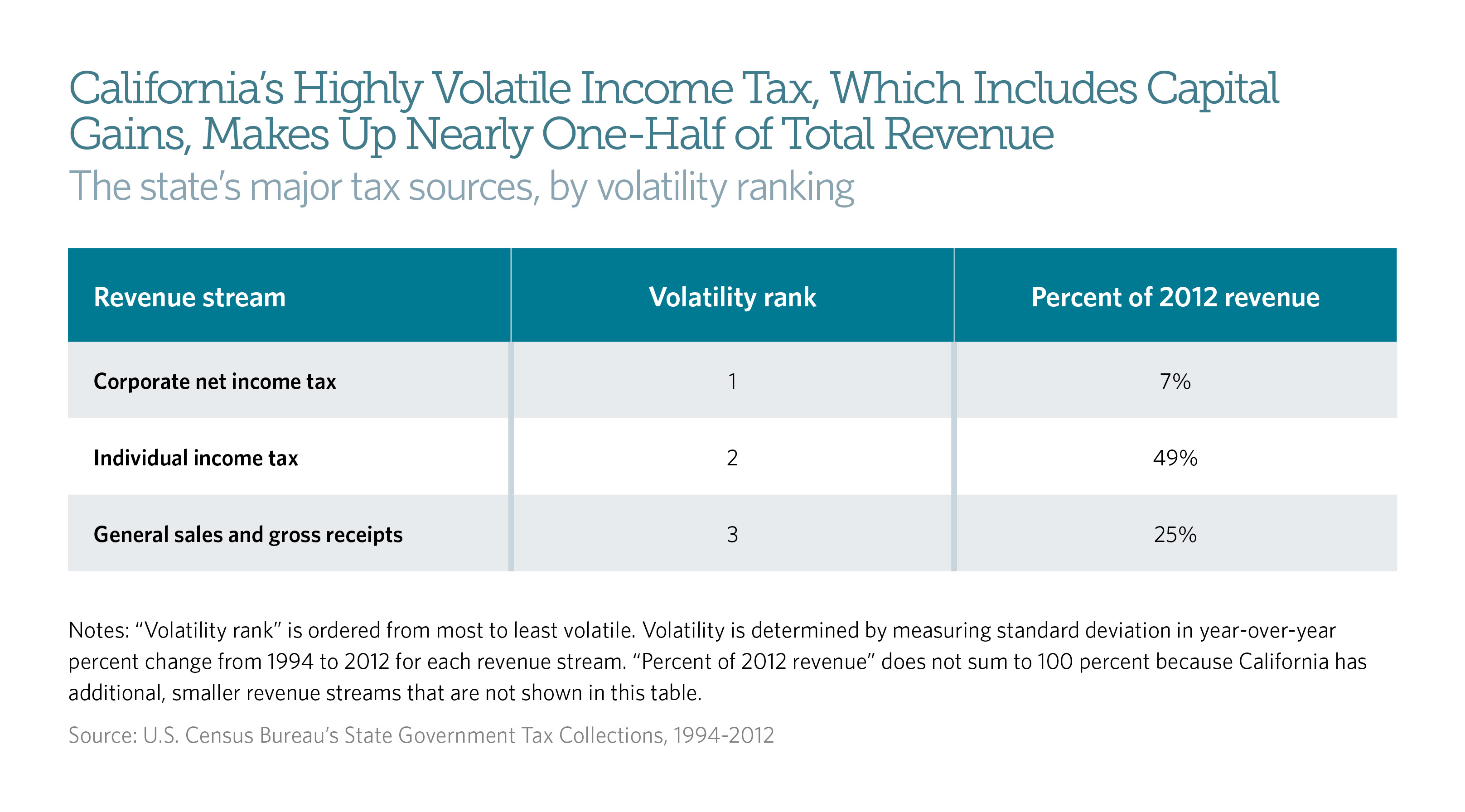

Capital gains revenue, which is expected to bring in about 10 percent of total general fund revenue in fiscal 2014, is a particularly volatile source of revenue in California that can fluctuate widely with the booms and busts of the stock market. In fact, swings in capital gains revenue drive much of the volatility in collections from California’s progressive personal income tax, the largest source of money for spending on state programs and services.7

Volatility in capital gains revenue often complicates the budget process during economic expansions. Forecasters say it is frequently unclear whether a spike in those collections is a one-time event or likely to become recurrent. But lawmakers may spend the extra revenue on programs or tax cuts with ongoing costs, which can be a problem in years when capital gains income is unexpectedly low. Under Gov. Brown’s plan, when capital gains receipts exceed 6.5 percent of general fund tax revenue—which has happened in eight of the past 10 years—the extra cash would be deposited into the rainy-day fund.8

The governor’s plan also would double the maximum size of the rainy-day fund from 5 percent to 10 percent of general fund revenue—the same increase outlined in ACA 4. In addition, his proposal would limit withdrawals during the first year of a recession to no more than half of the fund’s balance and would give the state the option of using the fund to pay long-term liabilities.

Managing uncertainty

The governor’s proposal needs two-thirds approval from lawmakers to replace ACA 4 on the November 2014 ballot. Assembly Speaker John Pérez, who previously suggested linking savings to capital gains volatility, supports the governor’s proposal, and Senate President Pro Tem Darrell Steinberg has praised what he called Gov. Brown’s “aggressive approach” to more than double the reserve and pay down debt.9 Both the Standard & Poor’s and Fitch credit rating agencies also commended the governor’s proposal.

If voters approve the plan to link rainy-day fund deposits to specific drivers of revenue volatility, California may point the way for other states that are considering redesigning their budget reserves.

California is not the only state where reserve funds are getting attention this year. After depleting reserves during the 2007-09 recession, many states are trying to replenish them. In some states, such as Connecticut, Idaho, Minnesota, and Nebraska, recent discussions focused on the proper size of rainy-day funds—that is, how much each state should save to prepare for the next downturn. In other states, such as Arizona, New Hampshire, and Wisconsin, policymakers are concentrating on end-of-year surplus allocation and are considering ways to balance reserve deposits with other budget priorities. Despite a recovery in revenue, combined reserves for the 50 states—counting both general fund ending balances and rainy-day funds—are not yet back to prerecession levels. As of fiscal 2013, states could cover a median of 30 days of expenses using their reserves—11 fewer days than in 2007.10

Findings from Pew’s research

States withdraw money from budget stabilization funds primarily to counter unexpected drops in revenue. Pew research has found, however, that most states do not consider revenue fluctuations in determining how and when to deposit money into their reserve funds. According to “Managing Uncertainty,” Pew’s report on strategies to smooth revenue volatility, only a dozen states, including Massachusetts, Texas, and Virginia, link deposits directly to unexpected surges in volatile tax streams. California could join this list of states if Gov. Brown’s proposal passes.

Pew’s research also points to some additional measures that California and other states can take to reshape or fine-tune their reserve policies to manage financial uncertainty more effectively.

One essential step is for officials to understand their state's unique revenue patterns. Although volatility is not inherently bad, wild swings in either direction can confound efforts to accurately forecast revenue and keep budgets in balance.11 Performing regular revenue studies allows state leaders to understand which tax streams drive volatility and how they change over time and then to better manage those ups and downs over the long term. Although the California Legislative Analyst’s Office conducted a comprehensive study in 2005, a regularly scheduled examination is recommended.

Next, linking savings to revenue fluctuations is an effective way to harness surpluses. California is expecting budget surpluses in the next six fiscal years.12 Because the sources of volatility vary from state to state, no single deposit rule will work for all states. Further, deposit rules may need to change over time because those sources of volatility can shift. A rainy-day fund design that evolves with a state’s economy and tax structure is central to managing budget uncertainty:

-

Utah, for example, completes a volatility report every three years and incorporates those findings into reserve fund policies. The state has increased limits on the size of its two reserve funds twice since 2008 to reflect changes identified by those studies.

-

Virginia compares total tax revenue growth with that of the previous six years to identify expansion above trend. This allows the state to make deposits to its rainy-day funds during years with surpluses, while maintaining budget flexibility during down times.13

-

Massachusetts links deposits to the same tax source that Californians are discussing—capital gains. Its deposit rule, adopted after the state drew down reserve funds during the Great Recession, has allowed Massachusetts to more than double its fund between 2010 and 2012.14

In California, both proposals under discussion would tie rainy-day fund deposits to a measure of revenue volatility. The ACA 4 proposal ties savings to unusual growth in overall tax revenue, while the governor’s recommendation would connect savings to a specific driver of revenue fluctuations—the capital gains tax. Critical details remain to be worked out, including the appropriate level of savings needed to prepare for the next downturn, rules for withdrawing and using reserve money, and ensuring that deposits are made according to the adopted rules. Ultimately, the Legislature will put one of these proposals before California voters in November.

Endnotes

1 According to the Governor’s Budget Summary 2014-15 released in January 2014, revenue will exceed estimates by $6.3 billion between fiscal 2012-13 and fiscal 2014-15. Gov. Brown is proposing to deposit $1.6 billion of that amount into the rainy-day fund, leaving $4.7 billion for other spending priorities over the three-year period. See Office of Governor Jerry Brown, “Revenue Estimates,” in Governor’s Budget Summary 2014-15 (Sacramento, January 2014), 161, http://www.ebudget.ca.gov/FullBudgetSummary.pdf.

2 The Budget Stabilization Fund is one of multiple reserve funds in California. In addition to the Budget Stabilization Fund discussed in this brief, California also has a Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties that captures surplus revenue, which the state has traditionally used in economic downturns. Deposits to this fund are based on the lesser of: (1) the General Fund unencumbered balance; or (2) the difference between "appropriations subject to limitation" for the fiscal year then ended and its "appropriation limit."

3 The fund’s total size is capped at 5 percent of general fund revenue.

4 Phil Oliff, Chris Mai, and Vincent Palacios, “States Continue to Feel Recession’s Impact” (Washington: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 2012), http://www.cbpp.org/files/2-8-08sfp.pdf.

5 The only states reporting lower reserves to the National Association of Budget Officers were Illinois, with 1.8 days’ worth of operating costs in reserve at the end of fiscal 2013, and Arkansas, which routinely reports zero reserves and balances.

6 These unanticipated dollars would be transferred to the rainy-day fund only if the state is already fully meeting its obligations under Proposition 98 to fund schools and community colleges. If these obligations are not already met, unanticipated revenue would first be used to pay the state’s education obligations; any remaining balance would be deposited in the Budget Stabilization Fund.

7 The state’s three main taxes are personal income, sales and use, and corporate.

Elizabeth G. Hill, “Revenue Volatility in California” (Sacramento: California Legislative Analyst’s Office, January 2005), http://www.lao.ca.gov/2005/rev_vol/rev_volatility_012005.pdf; see also Mac Taylor, CalFacts 2013 (Sacramento: California Legislative Analyst’s Office, January 2013), http://www.lao.ca.gov/reports/2013/calfacts/calfacts_010213.pdf; Office of Governor Jerry Brown, “Revenue Estimates,” Governor’s Budget Summary 2014-2015, 163.

8 “Understanding California’s Fiscal Recovery” (New York: Standard & Poor’s Ratings Services, Jan. 14, 2014), 4. http://www.standardandpoors.com/ratings/articles/en/us/

?articleType=HTML&assetID=1245362956902

9 Office of Governor Jerry Brown, “What They’re Saying About Governor Brown’s 2014-15 Budget Proposal,” Senate President Pro Tempore Darrell Steinberg (Sacramento, Jan. 13, 2014), http://gov.ca.gov/news.php?id=18360.

10 See The Pew Charitable Trusts, “Fiscal 50: State Trends and Analysis” (2013), http://www.pewstates.org/research/data-visualizations/

fiscal-50-state-trends-and-analysis-85899523649#ind5.

11 The Pew Charitable Trusts and the Nelson A. Rockefeller Institute of Government, States’ Revenue Estimating: Cracks in the Crystal Ball (March 2011), 3, http://www.pewtrusts.org/uploadedFiles/wwwpewtrustsorg/Reports

/State_policy/States_Revenue_Estimating.pdf.

12 Mac Taylor. The 2014-15 Budget: California’s Fiscal Outlook (Sacramento: California Legislative Analyst’s Office, November 2013), http://www.lao.ca.gov/reports/2013/bud/fiscal-outlook/fiscal-outlook-112013.pdf.

13 Virginia Secretary of Finance Richard Brown, pers. comm., September 2013.

14 Comptroller of the Commonwealth, Research and Statistics, “Commonwealth [of Massachusetts] Stabilization Fund,” http://www.mass.gov/osc/research-and-statistics/commonwealth-stabilization-fund.html.